I am not the parent I thought I’d be, but revolutions rarely unfold as we predict

I had two families; at least one of my childhood, and my other was the direct action movement in the UK. I came to Motherhood with a host of political values and beliefs that I imagined could be put directly upon that particular project. But these ideas and ideologies — some helpful and some unhelpful — could not just be transferred over into that relationship.

I recognise not everyone has the same experience of parenting, and mine has been particularly fortunate (after the first monstrous year). I used to believe that babies came into the world a blank slate and we created whatever we wanted from them, just as I believed the revolution was right around the corner, but I lean far more to a biopsychosocial model now — a combination of biology, psychology and socioeconomic factors. Parenting my son has forced me to adapt, just as all our key relationships do and should. It is not one will over another, but a dynamic; mutual aid if you will.

Fast forward to now and my son is a few months from that somewhat-spurious adult mark of an 18th birthday. Our relationship is richer and deeper than I ever imagined possible. I write a blog on new narratives of masculinity called The Boys Are Alright about how parenting a son could be a particular challenge to contemporary feminism, especially in a cultural desert of positive stories on boys and men. I’m a different person now — because raising children changes you, and even biologically bearing them changes your very cell structure — but that’s nothing to do with the horrible adage about getting more conservative as you get older.

That adage may be becoming more obsolete.

My son’s generation is polling both increasingly conservative and increasingly progressive. Criticised for neither caring enough about politics and for being too woke. Some studies are suggesting this is a two-way split, a trend seen nationally, with young women moving left and young men either staying central or moving to the right. Very recent polling on electoral voting has Reform UK lapping up support from boys aged 16-17 at 35% – but only 8% from girls. Others are pointing to a trend of far right populism capturing the hearts and minds of not just Gen Z but much younger groups — across Europe part of its electoral success is attributed to lowering the age of voting to 16. In France, 32% of youth, irrespective of gender, supported National Rally. The ultra right AFD has incredible popularity amongst the young in parts of Germany. These aren’t outliers. Similar trends are observed in Italy, Portugal, Belgium, and Finland. Mainland Europe is increasingly bleak.

This means that boys like mine who care about a better world face moving in the opposite direction to vast swathes of their generation, working against peers who lean towards the far right and even fascism. And we’ve recently seen in the UK how frighteningly quick the catchier of these ideas can become an immediate physical threat.

“If there’s one thing worth reiterating it’s that your generation’s left is a very different landscape to ours”, my son presses home.

We have our own divergences — I come from an anarchist and activist tradition, his is more red than black. The generalisations I make here are sweeping and to be held lightly. His generation seems far more directed toward individual and personal concerns — their identities, their mental and physical health — whilst at the same time engulfed with stress about climate change, and intensely engaged with geopolitical causes such as Palestinian liberation.

When we discuss the horrors of Project 2025 which a Trump election threatens, his primary concern is trans rights. Mine is global ecological devastation. We eye each other across the generations with both connection and confusion. We’re on the same side; but our priorities are very different.

Partly we have different ideas of what is possible. Mine was a radical vision of another world. His is about hankering down. He tells me it isn’t that they aren’t bothered by environmental collapse, but they’ve been told for all their lives that it’s happening. Climate activism is not a dominant youth movement, despite the odd Greta and school strike, but actually more the terrain of the over 40s.

A generation with smaller dreams

I’m sure the reasons are plentiful and complex, but what they aren’t about is this being a “selfish” generation. From homes and education to the cost of living — working class youngsters have been seriously screwed even within the thin promises of capitalism and its progresses. At his age, I was not only able to leave home but also to focus outward and take risks. I skimmed through my A-levels rather than sweating them. In terms of affordability and availability, adventures were there to have. A few years older than him, there was nowhere in the world I didn’t feel I could get to somehow and where someone would put me up (or where I’d find a squat I could sleep in). It was easy to earn money, it was easy to sign on, and you even got paid to go to university. From the mountains of Chiapas to the streets of Seattle, another world was possible.

The geopolitical focus of now and then matters, because then we were looking to hope, to possibilities, asking what other societies are building that we can learn from. We were creating anti-capitalist global networks to build a new and just world in the shell of the old. We looked at resistance movements we were akin to or inspired by. It seems that for his age group, it is more about who are the worst victims of geopolitics, who suffers the most, rather than who resists in ways we can learn from. Why do Gen Z’s eyes focus on the prison of Palestine — a recentring of an old theme — and not on supporting the feminist and collectivist aspirations of Rojava? It can’t be because the politics of Hamas are more desirable and laudable than those of the YPG, so I wonder if the vision of this generation is centred on survival rather than on an ambitious craving for another world.

It feels like back then we had big, big dreams and that those of us who bucked the anti-breeding trend of the direct-action movement are now parenting a generation with smaller dreams. Gone are the temporary autonomous zones of protest camps in woods and squatted social centres, at least in this country. The radical youth are instead returning to the more traditional left. Security, rather than freedom, is a priority demand for both the progressive and the regressive kids in my son’s generation, as they all bunker down. He would like more cameras on the streets, more state control. We disagree on the importance of freedom of speech. My interests in pushing boundaries and anti-censorship make me a dinosaur.

Without the dynamic of us being a unit, a team, without the connectedness of our everyday life and love, I wonder if these different political priorities would feel like chasms, whether we would feel like we are on opposite sides of a battle, whether we would be more enemies than comrades. But we have love. We know each other enough to tolerate the places where we feel quite opposite, we can understand each other enough to manage issues that have split movements.

Yet I struggle with political disagreements with my son. I’m much more likely to call it quits on a discussion that’s proving controversial because my desire to stay close outweighs my desire to explore ideas. At his age my furious disagreements with my parents were part of ruptures that never healed, because it’s not family that inherently ties us, it’s love. In my family of origin there wasn’t enough care to contain the conflicts. My biggest fear would be that there’s rupture and no repair, that there’s such stark divergence there can be no coming together.

But whilst my first family taught me that it was easy to walk away, my second one — the direct-action movement — taught me about the resilience of relationships. It’s perhaps no surprise that I live a few minutes’ walk from those I struggled alongside for decades, who I loved (and sometimes hated and raged at) whilst we collectively fought the good fight. The allegiance of collective struggle is one that my son’s generation is less likely to experience. They may be riddled with fear of the climate crisis, but with less hope of changing the world and with more draconian prison sentences. They aren’t as likely to be on a physical frontline together, only on an electronic one, which makes for far less bonding.

And if I could grant his generation anything, it would be the solidarity, loyalty and connection that comes with the former.

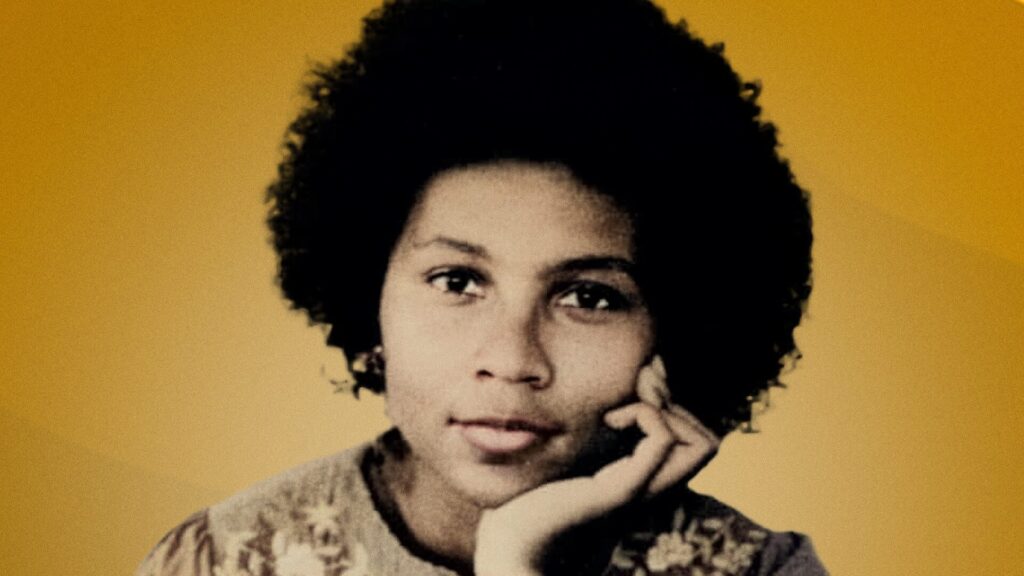

~ Tabitha Bast

SOURCE: Freedom News