Abstract:

It is widely known that Greece faces one of the most precarious and transformative periods of its modern history. Greek society has come to learn, in a baleful manner, that crisis is the sequence of its former political inefficiencies and a slump that must be overcome. The pressure of this awareness leads people to deface previously established social convictions about the self and the world. In this procedure, social and mass media articulate and (re)produce discourses from above, below and the past so to capitalize the present for a new and solid horizon for the future. This article challenges five beliefs that circulate in the Greek public sphere inculcating their incontrovertible realities: the end of Post-Polity era (the ‘former’ political status quo of Greece known as Metapolitefsi), the revival of ethno-socialist movements, the debt crisis of eurozone countries, youth’s stand for social change and the role Greece plays in this global financial turmoil comprise the contents of this critical debate. What I suggest, is that apart from the obvious misfortunes of crisis, the performative effects of the imposed vision of the well-regulated state brings forth collective feelings of offence and oppression in such ways that old divisive ideas about Greece are awaken, reducing the country to a zone of social change in which the subject renegotiates its sense of individuality and community.

Introducing a precarious state

The name Metapolitefsi has come to identify the last 30 years of civic life in Greece. In Greek it means the transition from one regime to another or from one way of being involved in politics to another. In the contemporary collective consciousness though, the name embeds the fall of junta in 1974 and the institution of parliamentary democracy. For British historian Mark Mazower (2000: 7), the name is connected with Greece’s ‘return to some semblance of tranquility’ after ‘Europe’s bloodiest conflict between 1945 and the breakup of Yugoslavia’ among the Left and the Right that started even before the Second World War. The seven-year junta, he observes, was the last bloody chapter of this civil conflict and, for that, Metapolitefsi embodies the promise of a new governmental state deprived of the terror of ideological persecutions and national disunity.

The term Post-Polity I use, aspires to capture the three-fold quality of the name Metapolitefsi that itself obscures due to its historical weight: the political changeover of the year 1974 (what is widely accepted in the Greek public sphere), the transition of one regime to another (the etymology of the word itself) and the promise the preposition post (Meta) withholds, both as an effort to heal past wounds and a quest for a new future. The Post-Polity regime that characterizes the last 30 years of Greece is indeed so grounded to this promise, that it is unattainable to fully understand the political transitions that happened within – such as Greece’s dedication to the European vision and the ideal of the socio-democratic welfare state – or the collective feeling of distress that have grown since 2009 due to the austerity measures taken as to deal with the so called ‘debt crisis’, without taking seriously the resurgent discourses about the ‘end of Metapolitefsi’ that characterize today’s political rhetoric. In the present year of 2012, Greece is under the International Monetary Fund’ s (IMF) instructions for structural reforms inherent to the neo-liberal paradigm and, as a result, a new horizon is procreated ‘from above’ with multiple side effects in the way people deal with their current predicament.

June’s 2012 election results evinced the five-year Greek depression’s simmering trends; yet they still came with a shock for the public sphere. They were a shock, above all, because of the destined way the results affirmed themselves: the striking fall of the once dominant socialist party, the change of the two-party system after the youth, the ‘indignants’ and many other frustrated people’s turn to the radical left, and the rise of the ethno-socialist movements are some of the tangible events registered in the Greek social body. At that time, voters and candidates, dazzled in front of the T.V. screens, ruminated over the ‘already’ predicted yet seemingly unforeseen outcome. Fated and expected as they were though, the Greek election results still mask the presence of all these rampant and perilous events that color the current socio-political setting: anti-immigrants attacks by armed para-state nationalist groups, forest arsons on the eve of the election and stock market sabotages with en masse capital flight affirm and expose the frightful financial and political web. This unnerving scene cannot be seen as a consequence of Greek crisis alone, but as a constitutive feature of this transitory period. Still, ‘Greek crisis’ can be a flexible field for apprehending and communicating the symptoms of this contemporary social change.

The post that never comes: ‘I’m living a dream, don’t wake me up!’[2]

Since the arrival of the IMF and the official announcement of crisis, debates about the end of Post-Polity era has dominated the political discourses. At the same time, the ‘post’ of the Post-Polity regime was speculatively linked to the causes of the current misfortune and the IMF’s proposed reforms. In brief, the ‘end of Metapolitefsi’, has marked today’s collective imaginary, in reference to crisis only – a condition I would like to discuss as a starting point for my reflections. The German literary critic Andreas Huyssen discusses the ‘end of modernism’ in a similar manner. He sees postmodernism as a field of collective memory for the imaginative production of modernism. ‘The problem’, as he says, ‘is not what modernism really was, but rather […] how it functioned ideologically and culturally after World War II’ (Huyssen 1986: 186). In a way, the post for Huyssen has been introduced in the context of a disengaging process and has served for the production of knowledge(s) displaced from the modern myths of progress and rationality. In a similar fashion, I believe that the post of the Post-Polity era exists only as a performative gesture of retrospective accusation that functions as a political tool for the discomfiture of the Post-Polity societal claims for a socio-democratic welfare state, and for the acceptance of the sacrifices needed to reform the Greek society – in the neo-liberal paradigm – for its return to much awaited political and financial stability.

Thereby, the identity of that post media usually portray to make the need of a new structural paradigm more plausible and appealing doesn’t indicate an already here present. It rather belongs to a manifold process of incriminating Greece’s recent political past, aimed to support the abrupt importation of neo-liberal reforms formerly considered ‘extreme’; disclosing, at the same time, the empowerment and encouragement, in a local level, of ‘the same global rhetoric about horizons of long-term economic growth’ (Guyer 2007: 410). Thus, this incrimination process serves for the penalization of the epistemic and ideological platform of the Post-Polity regime, leading all previous governments to a rampant criticism in terms of corruption, misappropriation and embezzlement. In result, the identity of that post as an outcome of this incrimination performance synthesizes and channels a public demand for a complete political change; a demand though, in which the ideological platform of these streamlined accusations is delicately masked.

To understand the identity of the post of the Post-Polity era in accordance to the sensitive issue of the societal claim for change, we have to ruminate over the imaginative construction of the past by the media and their capacity to effectively channel public’s discomfort and complaints. It is imperative in order to understand the massive salary and pension reductions – in some cases exceeding the 50 per cent – the increase of working hours, the extensive dismissals of bureaucratic personnel, the increase of personal taxes and the discontinuing of many social provisions; measures impossible for a previous government to take, and now enacted in only three years time. Because, for a society to accept the dismissal of all its social accomplishments, means to feel critical for the whole infrastructure that made them possible in the first place. So, Greece performs this ‘new’ identity of the post, by preserving a collective trauma (i.e. corruption, as the bankruptcy of Post-Polity’s promises) so to recast the image of its past and to extort a different – yet once criticized – field of innovations. Thus, the post of the Post-Polity is not a temporal event but an affective condition grounded in the population’s unconfessed complicity for the failures of Greece’s former political and economical life. A complicity (re)produced dialogically with the praise of a lawful and congruous state in the liberal market context.

The return of the damned as (mass-mediated) democracy’s self-punishment

The imaginative construction of the Post-Polity era was heralded in with the establish-ment of the democratic constitution. At the time of the 1980s, the opening of the press and television market to private interests, attached Post-Polity governments to the tele-visual way of conversing with people and to mass media holders’ political and financial interests. In the affective condition of the post, this notion of ‘financial interests’ pertains to a grid of secret, masked and undercover agreements that is not only used for the incrimination of Greece’s most recent political past, but also for the mystification of the current situation in terms of conspiracies and concealed – global or otherwise – plans.[3]Consequently, one of the manifestations of the political strategy to implicate Post-Polity in the ordeals of the present is a sound distrust towards political life as a whole, in addition to the general disregard of the (social)democratic welfare.

In the Greek public sphere’s collective imaginary, democracy’s corruption is felt, first and foremost, in the collapse of expectations that were cultivated by the two main Post-Polity parties. Previous election slogans remain engraved on voters’ memory, such as ‘The citizen first’, ‘Greece first’, ‘Hat-in-hand’[4] and ‘People won’t forget what the Right stands for’[5], they are now internalised in the affective condition of the post and are inverted from their initial meaning producing a nervous turn towards nationalistic and patriotic movements; particularly towards the one that vaunts for authenticity: Golden Dawn. The slogan ‘The citizen first’[6], as the last ‘lie’ of the Post-Polity era becomes, in a reflective way, the ground for questing that promise’s literal sense through the shadows and the ghosts of the now wounded democratic system. In other words, mass-mediated democracy’s promises are quested through the constitutive Other of Post-Polity’s regime, which is the ‘reprehensible’ ethno-socialist ideal.[7]

This turn to patriotic movements is, obviously, coherent with the ultra right-wind streams of fanaticism that dominated Greece in the years after the civil war (see Mazower 2000). The Post-Polity regime had denoted, in a reserved way, the termination of the ideological divisions through Greece’s devotion to the European social-democratic ideal. And despite its incrimination, most people are not willing to ‘remind’ themselves the post civil-war traumas.[8] Since Golden Dawn’s allocutions are disjoint from previous military languages, the ‘politics of memory’ which permeate the political disputes of Post-Polity create a political space in line with the affective condition of the post. Namely, Golden Dawn’s rhetoric of hate on leftists, corrupted politicians, gays, foreigners, artists and academics, is based on an accusation of national betrayal due to financial, diplomatic or other partialities. [9] This is the common ground that relates the incrimination of the Post-Polity regime with the fanatic ruffle of Golden Dawn: the affective condition of guilt being embedded in the madness of revenge.

Thereby, Golden Dawn, the political party/movement that, as mass media portray, cannot be controlled by ‘democracy’ shines through the darkness it promises and its unlawful attacks against the corrupted political system. In voters’ consciousness, Golden Dawn becomes the par excellence agent of blackmail that places the ‘citizen-punisher’ into parliament life. It also becomes the carrier of the reformed model of ‘citizen’, a one that needs protection from the mass media, which are presented by Golden Dawn as an instrument of the threatening global forces that lead people to precarious states with their conspiratorial policies of nation, race and gender boundary disturbance. The paradoxical relationship of hate between Greek mass media and the Golden Dawn party reveals the power and the limits of modern mass mediated democratic system, in which the claim for the ‘lost’ democratic ideal brings forth inglorious movements for democracy’s complete and apocalyptic disablement.

Greece in a ‘state of emergency’ or the state of exception as a condition of crisis

It was after the elections of 2009 that Greece entered into economic ‘crisis.’ Its public announcement came from the lips of the newly elected prime minister himself, G. A. Papandreou, who declared that Greece now was in a ‘state of emergency.’ On his invitation, consultants from the European Union (EU) and the IMF arrived in Athens in no time to help the government take the necessary steps to decrease the deficit and improve the economy overall. This governmental discourse on Greece’s ‘state of emergency’ – as Greece’s state of exception from the markets – was necessary for today’s crisis to take shape and for the stigmatization of the Post-Polity regime as responsible for it. Additionally, the vision of a lawful, modern and Europeanized state became the rule for this ‘state of exception’ to take shape, presaging and arranging a field of changes and reforms which without crisis wouldn’t have been possible; and to which not only Greece but all European countries must conform. Mass media and political agents were the main channel for this grand narrative to take form and until now the vision of a modernized state is still the one that acts as a metaphor for a desired outcome.

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben uses Carl Schmitt’s concept of ‘state of exception’ to investigate the exceptional measures taken in periods of political crisis. He believes that the legal measures taken in states of exception cannot be easily understood from a legal point of view. For him, they are political, insomuch as the state of exception entails the paradoxical position of presenting itself as the legal form of that which can have no legal form. He, then, stresses the importance of the condition in which the state of exception becomes the rule, so the exceptional measures turn into government techniques and, as a result, the once familiar form of political constitution loses its traditional distinctions (Agamben 1998: 122). In a way, since this evasive state becomes the rule, an opening for a space devoid of law occurs where different power relations may become proximate As he puts it, the state of exception is the provenance of every juridical placement since it opens up a space for the stabilization of a new kind of order (Agamben 1998: 19).

Using Agamben’ s analyses, we may say that the Greek government’s decision to except Greece from the markets, due to its inability to fulfill its debt obligations, and put it under IMF’ s patronage, as the figurative schema which supervises and controls them, is not just part of a procedure that disciplines or re-programs Greece (what both ill or well disposed discourses tend to put forward) but rather a part of one, that tests the ability of the EU to sanction the new principles of its restructuring. A speculation that leads us to think that the abrupt reforms Greece is forced to adopt belong to a political intention of reforming European governance. So, in a way, Greece, the last geographical and financial frontier of the EU becomes, simultaneously, the barometer of European deficiencies and the laboratory of multiple strategies for EU reform. In this sense, the ‘advanced European country’ as the rule for the ‘state of exception’ to take shape becomes the exception itself, for Greece becomes now the lawless space in which the ‘new European country’ is procreated. The fact that G. A. Papandreou declared with such ease ‘either we change or we sink’ to every European council denotes that there is a vision of a new financial, governmental and state order at stake, which is continuously being exceeded as a trace, although never denominated as such.

Thus, we may assume that the danger of Euro’s collapsing doesn’t just show the ‘structural’ problems of the European countries, but, much more, it shows the liberating ‘structural’ solution of a more coordinated, flexible and effective governing mechanism. The language Europeans officials use, such as the statements German and French prime ministers frequently make about a ‘European government’, a ‘trans-European executive authority’ or a constitution of a federation like the United States of America (USA) don’t belong to an abstract vision of European consummation, but they hold a very specific projection of a modernized European future, which is being anticipated in the present as a virtual horizon through this crisis. In this fashion, the ‘event of crisis’ is not just an objective social and economic matter needing attendance, but a bio-political laboratory of key signifiers that connect everyday life with the projection of the future.

Youth’s stand for change: ‘In these elections, we hide our grandparent’s ID cards!’[10]

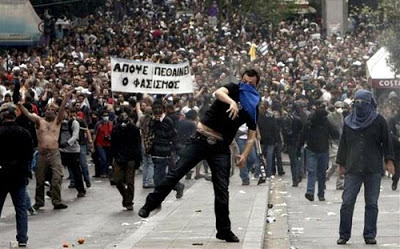

Greek society is filled with outbursts of riots each and every time a package of austerity measures passes the parliament. Images of the most raging scenes are traveling around the world declaring, in a way, that the Greek public denies to submit to a change imposed ‘from above’. We might say that this disobedience belongs, in some measure, to the same spirit of demanding political change, as the one that Theodore Roszak (1968) finds in the ‘counterculture movement’ which flourished in the USA and Western Europe in the 1960s. In his effort to make sense of the huge wave of confidence people had in changing the world, Roszak observes that 50 per cent of those populations was below the age of 25. In respect to his observation, I ought to note, that Greece of 2012 has 50 per cent of its population over the age of 40;[11]and it is this part that accomplished its life-goals at the Post-Polity era. That means that a great deal of the Greek population operates with an outward mark of obeisance towards the austerity policies, in fear of losing its vested interests; while simultaneously, the young productive force embodies this part of society that craves for change, as it suffers the unbearable violence of austerity.

This picture becomes a lot evident during the months running up to the June 2012 election. that were marked with massive protests, riots and acts of disobedience. The confirmation of the belief for ‘discipline’ found Greeks tacitly divided, facing, through this ‘involuntary’ choice of austerity, memories of this ‘long forgotten’ polarization between the Left and the Right. Through the 30 years of Post-Polity, these oppositions may had been smoothed over, but, as Danforth and Boeschoten (2012) have shown, there are still strong communities of memory – people that have witnessed the civil war – that ‘would vote’ for stability only to ‘forget’ the past. That is, this belief for discipline fully embodies the memory of past national misadventures, while the youth, in an ironic way, incarnate the part of the population that crave for change; even in the cost of dismantling the relative peace made in the Post-Polity era.[12] Thus, being young in modern Greece means to feel a minority force in the construction of Greece’s future. For a young person, to live in Greece means to partake in the collective depression of seeing his/ her expectations and demands be set aside for the sake of older people’s (bank accounts) safety and their fear of new national misadventures. Hence, current prime minister Antonis Samaras’ rhetorical campaign dwelled on the catastrophic scenario of Greece’s exit of eurozone is not such a surprise; as timid and divisive (and alien to the youths) as it was, it intended to reach the terrified ears of the seniors. It was also of no coincidence that in his first post-election speech he was eager to thank ‘the masses of youth that supported him’.

Half of Greece’s population has experienced the post-war, post-occupation and/or post civil-war traumas. It grew up out of ‘nothing’, yet with plenty of opportunities to make its dreams possible. It also grew up with the need to escape rural life and the desire to live the modern urban, consumerist (and with one or two kids) nuclear family life. Greek families, as shown in respective ethnographies, are formed with the principle of ‘honor’. That is, the collectivity of the family is bounded when the individual’s shares and interests conjoint with the safekeeping of the family’s private sphere. Many theorists (Campbell 1983, Herzfeld 1987) have pointed ‘honor’ as an indicator for both structural continuity and social change. Despite differences, all commentators will agree that massive urbanization and industrial modernisation have shifted the ways ‘honor’ is manifested, yet it is still a way to understand the boundaries of the family by means of individual action. Yet, in the site of crisis, this ‘peculiar Greek individualism’ (Abdela 2002: 218) is presented in ambivalent terms. Because the boundaries of the family seem to frame both of these contradictory tendencies of muffled safety and rabid escapism; denoting the multiple articulation of ‘honor’ itself which family’s private sphere retains.

On one hand, the image of the paternalistic Greek family gets blurred in the misty shadow of crisis and reveals an opportunistic dimension which face such a concern for its offspring’s future, that it even accepts their sacrifice. On the other, the idea we have of the overprotective behavior of the Greek family shatters with the ‘event of crisis’, as ‘honor’ is detached from the strict connotations of the family’s private sphere’s interests. Through these multiple shiftings in individual concerns, the ‘young’ are forced to claim a space of ‘adult’ decisions and deny a juvenile precariousness, nourished by their elders. For the adults, a sense of sacrificing the most sacred gifts like security and (paternalistic) protection is produced, with their offspring as the first victims, who now ought to re-learn how to be modern. Thus, current youth’s stand for social change is not just clashing with some restraining and conservative forces (what can be easily conceived through the mainstream ideological platforms) but with an attitude of passive impartiality that shares this uncofessed complicity for the ‘failures’ of the past. Crisis, as it seems, is another plateau of modernization where the Greek subject reconfigures its individuality and sense of community. It is a contemporary rite of passage for Greek society; a process of violent adultness for all generations.

Greece, the cradle of the world.

In an article of his that was popular within the Greek public, British historian Mark Mazower (2011) says that Greece’s national history goes hand in hand and sometimes presages the great changes of the modern western world. The 19th century great empires’ fall, the adventure and collapse of Nazism, the European cold war division, the expansion of the EU and now the crisis of the worldwide financial system spark are, as he points out, resultants of modern Greek history. At the same time, the little country of Greece acquires the heroic and tragic role of being ‘in the forefront of the fight for the future.’[13]I don’t find the real role of Greece in the worldwide theatre of changes that important; to my mind, each country partakes with a different role and degree of tragedy in this play. But, what I really find interesting is that Mazower takes up a philhellenic tradition in a time of war; representing Greece’s various resistances ‘as the noblest of causes’[14].

In a non-committal way, this popular article belongs to a storehouse of help that encourages the revival of the Greek spirit, by internalizing in the collective imagination the belief of a ‘Great Greece’ that holds the capacity of an explosive way of participating in ‘worldwide negotiations’. Having the feeling of this capacity means to cultivate, in a collective manner, the conviction that not only Greeks are capable of, but it is incumbent upon them to counteract against any assault to their private/national domain. The ability to unilaterally terminate the memorandum and to refuse paying off the debt, as well as the ‘invitation’ of an ultra-right wing ethno-socialist party in a European parliament, belong to the same reactionary context fed by a tank of allegories that share a common psychic denial best understood with the psycho-analytical themes of sublimity, egocentricity, narcissism, fear of loss, inability to accept criticism and various vindication fantasies.

What I actually want to say here is that the existential fear of a country in crisis, once it internalizes the capacity of assaulting the worldwide financial web, makes it ‘dangerous’ insofar as this country reflexively increases its metonymic power to protect itself by means of attacking the joints of the skeletal structure which finds itself entrapped in. So, to visualize the characteristics of a country in a precarious state, one has to bear in mind this shrewd oscillation between the capability of an explosive reaction and attending the exhortations for legitimacy. In that sense – and in a diametrical opposition to Mazower’s view – for a country to be ‘the cradle of the world’ means to be a screen for projecting the worldwide circulating needs for change and, at the same time, a camera that projects for itself the eventualities of crisis as a virtual horizon for the whole world. Greece as the cradle of the world is the crisis’ point of no return. And it resounds the crisis’s center since it has been reduced to a laboratory of multiple and contradictory narratives and metaphors of an imminent future through the most common conspiratorial stories of the hidden, yet terribly tangible, global financial relations.

‘Capitalizing’ these five thoughts

In illustration of what I have said, I am tempted to use another ‘common’ belief, one that is not only ‘Greek’ but, on the contrary, it resounds the global image of the modern and well-regulated state in the market’s context. It is the one saying that societies ought to control, as a moral stance, the financial steering wheel of their country. In the event of crisis, we can see that what this stereotype conceals is the disconnection of the steering wheel from the rest of the vehicle’s navigation system and its participation in automated, by ‘invincible’ programmers, steering movement transmission systems. In the context of Greek crisis, it is a matter of trust of a faded and frayed map, with a very great obligation involved in society’s part, to show a brave, authoritative and confident attitude. In other words, it means that what the Greek society has to prove is not that it can take the ‘right direction’, but rather that it can take on its back the burden of change imposed by the ‘international fund community’, as an after-effect of the harsh prescription for stability. Stereotypes like this, are not just vehicles for imposing, ‘from above’, the vision of a well regulated state, but they zigzag in monstrous rhythms in and out of multiple private and public spheres, producing ambivalent images of the self and the world (see Athanasiou 2007; Guyer 2007).

For the subject, the event of crisis becomes a zone for renegotiating the idea of self and community. The violence of this process is not just evident in the reduction of salaries and expenses, as politics of reform. It is presented in the products of this shrewd oscillation between the vision of a well regulated future and the apocalyptic dystopias of the present. This oscillation is an evidence of the contradictions of the eurozone figure as well. Because for Greek society to be in this crisis means to occupy EU’s margins and at the same time cry with all its strength about its inefficiencies. For the same reasons, EU learns through this crisis how to reinstate its authoritative and paternalistic role, by trying schemes and models for an updated inter-national paradigm. Therefore, the post of the Greek Post-Polity era is something more than Greece’s passing to a regime of risk and precariousness. It means that Greek society is living the parallel eventualities of crisis in which novel horizons are reflexively projected as the European rescue plans are being tested. In this condition, Greece becomes a social zone for reconfiguring its sense of orientation through facing the same divisions, exclusions and ideal projections which haunt its past and have made its present possible. And yet, the sense of its present is linked to the future as an image governed by the forces that control the financial steering wheel of the country. Ultimately, to capitalize on the present amidst a condition of crisis means to force a specific value onto the future; a value that conceals all the social and financial relations that produce it and sustain it.

Bibliography:

Abdela, E. (2002) “For Reasons of Honour”: Violence, Emotions and Values in Post-Civil-War Greece. Athens: Nefeli.

Agamben, G. (1998 [1995]) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. tr. D. Heller-Roazen. Stanford University Press.

Athanasiou, A. (2007) Life at the Edge: Essays on Body, Gender and Biopolitics. Athens: Ekkremes (in Greek).

Campbell, J. K. (1983) ‘Traditional Values and Continuities in Greek Society’. Pp. 184-207 in R. Clogg (ed.) Greece in the 1980s. London: Macmillan.

Danforth, L. M. & Boeschoten, R. V. (2012) Children of the Greek Civil War: Refugees and the Politics of Memory. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Guyer, J. I. (2007) ‘Prophecy and the Near Future: Thoughts on Macroeconomics, Evangelical, and Punctuated Time’. American Ethnologist. 34 (3): 409-421.

Herzfeld, M. (1987) ‘“As in Your Own House”: Hospitality, Ethnography, and the Stereotype of Mediterranean Society’. Pp. 75-89 in D.D. Gilmore (ed.) Honor and Shame and the Unity of the Mediterranean. Washington, D.C.: American Anthropological Association.

Huyssen, A. (1986) After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Mazower, M. (ed.) (2000) After the War was Over: Restructuring the Family, Nation, and State in Greece, 1943- 1960. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Mazower, M. (2011) ‘Democracy’s cradle, rocking the world’. The New York Times. [online]. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/30/opinion/30mazower.html?_r=1[Accessed 14 September 2012].

Papailias, P. (ed.) (2011) ‘Hot spots: beyond the “Greek crisis”.’ Cultural Anthropology [online]. Available at http://www.culanth.org/?q=node/432[Accessed 4 November 2012].

Roszak, T. (1968) The Making of a Counterculture: Reflections of the Technocratic Society and its Youthful Opposition. New York: Doubleday & Company Inc.

[1] This article belongs to an effort to ground “crisis” and its aftereffects to an academic glossary and debate. An earlier version of some of the arguments made here has been published on the Cultural Anthropology website (see Papailias 2011).

[2] A famous slogan coming from a Greek advertisement for mobile services. The protagonist – a hot dog seller – promises more ingredients than the other ones, building in a way a promise-land of goods that is within a grasp.

[3] It is very common in today’s anti-memorandum parties to take on discourses of “intrusion of the banking lobby”, “global loan sharks”, “media’s terrorism for the manipulation of voters” etc.

[4] It was one the basic instructions former prime minister K. Karamanlis (2004- 2009) gave to his ministers, to persuade the people of Greece that his government had no intention of being implicated in scandals and corruption.

[5] One of the most well known and repeated slogans of the socialist party of PA.SO.K. The slogan attacks the right-wing party, by “reminding” the society the seven years of military junta.

[6] It was the main slogan G.A. Papandreou used for PA.SO.K. pre-election campaign of 2009. At the second month of his presidency he called the IMF for financial support.

[7] I make this speculation due to the fact that Post-Polity’s ideological platform was built in difference to junta’s military governments and royalist regimes.

[8] For the ‘politics of memory’ in accordance with the Greek civil war adventure and post civil war main governmental policies, see Danforth & Boeschoten (2012).

[9] It is important to note that the main policy Golden Dawn is practicing the few months of its parliamentary service includes attacks and persecutions of immigrants and illegal vendors. Many times it responds to calls of frustrated citizens who are unable to get help from the police. One of the latest ‘rumors’ is an attack to a public hospital’s doctor who asked for a 2.500 euro baksheesh to perform an operation. Despite what is true or false, many people have cultivated an image for Golden Dawn as the punisher who will cleanse Greece from corruption. In addition, Golden Dawn says that ‘gays’ are the next target after immigrants. The first attacks on them being a fact.

[10] A slogan spread throughout the internet social networks among young people, at the time of Greece’s most recent elections.

[11] An estimation based on the 2011 Greek population census.

[12] Youths in Greece face most of the consequences of crisis. According to the National Statistical Service of Greece, the 55 per cent of the population under the age of 25 is unemployed (referring to July of 2012).

[13] With these words Mazower ends up his article.

[14] I’m using – in an ironic political way – the same words Mazower uses to describe the feelings the philhellenists had at the time of Greece’s independence war.

Acknowledgements:

I really wish to thank Athena Athanasiou, Penelope Papailias, Vanesa Ariza Olivera, Evy Vourlides, Natalie Koutsougera, Babis Kontarakis and the editors of the Unfamiliar Journal for their insights, comments, remarks and their overall help and support. Without their contribution this article would have never been possible.

Leandros Kyriakopoulos

Panteion University of Athens

Email: Leky@mail.com

You can access my papers on the Social Science Research Network (SSRN) at: http://ssrn.com/author=1706538

Leandros Kyriakopoulos is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Social Anthropology at Panteion University, completing a dissertation on psytrance festivals as heterotopias and experiences of the self as technologies of constituting humanness. His main interests include new mobility, electronic dance music cultures, new technologies, politics of place, transnationalism, identity, subjectivity.

Leandros Kyriakopoulos participates in Void Network and he took part in the creation of the book “We Are an Image from the Future / The Greek Revolt of Dec. 2008”, edited by A.G. Schwartz, Tasos Sagris & Void Network with the essay titled:

“December’s riots as mediated by the image of mass media”

you can read this essay here: here:http://libcom.org/library/december%E2%80%99s-riots-mediated-image-mass-media

for more info about Unfamiliar Magazine were this article first published:

The Unfamiliar- an Anthropological Journal

Vol. 2, Issue 2, Winter 2012, the University of Edinburgh

- 18-26.

The online version of the article can be found at:

http://journals.ed.ac.uk/unfamiliar/article/view/70