GATHER YOUR PEOPLE

WHITE WOMEN MUST HOLD EACH OTHER ACCOUNTABLE FOR RACISM

We know that 53 percent of white women voted for Donald Trump. We know that some white women are so blinded by their privilege, their racism, and a patriarchal system that insists their lives as wives and mothers are “precious” that they happily carry water for the white men in hoods and iron crosses. We know that some white women march right alongside them in neo-Nazi rallies, drop racial slurs on social media, and push racist legislation in Congress. And we know this has been going on for a long, long time—well before Trump’s Klansman father was born. However, viewing white women’s involvement in perpetuating white supremacy solely through their relationships with men not only denies their agency, but assuages their culpability. As the old saying goes, men talk, women do.

Historian Elizabeth Gillespie McRae’s new book, Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy, is a fascinating, meticulously researched, and damning look into the myriad ways white women have consciously worked to aid racial segregation in the Jim Crow South and sanctify their racially pure vision of white motherhood. The book focuses on four women—Florence Sillers Ogden, Mary Dawson Cain, Cornelia Dabney Tucker, and Nell Battle Lewis—across multiple generations of white-supremacist activism; it takes us from Deep South racism in the “progressive” 1920s to the mob of screaming white mothers who greeted Black schoolgirl Ruby Bridges in 1960 New Orleans through the Boston school busing controversy of the mid ’70s.

For decades, these four women and others performed “myriad duties that upheld white over Black: censoring textbooks, denying marriage certificates, deciding on the racial identity of their neighbors, celebrating school choice, canvassing communities for votes, and lobbying elected officials.” They taught their children that racial hierarchies were not only scientific and just, but actually God’s will; that Black people preferred segregation; Black boys were unintelligent and sexually overdeveloped; Black men were dangerous; and falling in love, marrying, or having children with Black men was the most horrific thing a white girl could do and would hasten the extinction of the white race. (The alt-right “white genocide” meme is nothing new). They formed political action committees, penned newspaper columns, passed out pamphlets, rallied for white-supremacist politicians, and leaned on their maternal image to manipulate the discourse.

After 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling destroyed the fictional idea that white people were the most responsible shepherds of racial justice and Black Americans were happy under segregation, these women pivoted to a family-focused political ideology that painted the Supreme Court decision as federal overreach that threatened mothers’ authority over their own children. This tactic attracted more moderate and liberal types to their cause, and effectively feminized mass resistance (a term used for the package of laws passed in 1956 that aimed to uphold Jim Crow and delay school integration). For white-supremacist women, the home and the school were their battlegrounds, and their most sacred duty as mothers was to keep them free of Black influence. According to McRae, without their efforts, “white supremacist politics could not have shaped local, regional, and national politics the way it did or lasted as long as it has.”

One of the more intriguing political tidbits from the book is the way white-supremacist politics criss-crossed party lines, with its proponents hopscotching between Democrat, Republican, Jeffersonian Democrat, New Right, and the catchall “conservative” tag. To simplify a complex development, following decades of pushing white supremacist policies, the Democratic Party’s growing acceptance of desegregation and racial equality inspired a mass exodus of white Southern women, and led them to seek representation elsewhere. McRae is careful, however, to illustrate that white-supremacist politics were not confined to the South; in cities like Milwaukee, Detroit, and Boston, white supremacy manifested under the cover of dog whistles and obfuscation, where parents weren’t racist for not wanting their white kids to share classrooms with Black students, they were just “concerned about school choice.”

The parallels between the past and our current state are stark, and often unsettling. Everything old is new again, just repackaged and refurbished to suit a new audience. We can find echoes of newspaper owner, columnist, and constitutional fanatic Mary Dawson Cain in the rise of both conservative pundits like Tomi Lahren and white supremacy mouthpieces Lauren Southern and Brittany Pettibone, all of whom espouse “traditional” viewpoints that range from casually racist to virulently white supremacist. Nell Battle Lewis—with her liberal education, outraged editorializing, and patronizing “color-blind” view of her Black acquaintances—is the spiritual foremother to today’s “woke” white feminists, who “don’t see color” and sport vagina hats with pride, but balk at any sort of intersectional analysis of feminism, privilege, or power.

We see the ideological granddaughters of Cornelia Dabney Tucker—who organized the sending of countless handwritten letters decrying the Brown v. Board of Education ruling—in the white women who now send panicked tweets about Black Lives Matter. Elsewhere, Florence Sillers Ogden’s efforts to brand the labor movement as “un-American” and blame outbreaks of racist violence on First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s willingness to freely socialize with people of color would fit right in on any race-baiting FOX News segment. Roosevelt was a target of ire for white segregationist women—her progressive politics and commitment to racial equality rendered her little more than a communist witch in their estimation; one can’t help but think of the way Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton—herself a polarizing, deeply flawed, yet (comparatively) progressive political powerhouse—was treated during her presidential run, and how much of the white female electorate turned on her in the end.

As I read their stories, I saw my mother’s face. The same cold, quiet cruelty that emanates from the photos in Mothers of Massive Resistance stared back at me 15 years ago, when she told me that my boyfriend Aaron* wasn’t allowed to come to our house for junior-prom pictures. He was a skater kid from a nice family who lived in a nice house in a nice neighborhood my family could have never dreamed of affording or fitting into—but since he had locs and dark skin, she forbid me from seeing him again. I remember how she told me, in what she must have imagined to be a comforting tone, “He’s a nice kid, but it just ain’t right.”

The lessons I learned about whiteness, class, and the lengths that white folks will go to protect their ideas have been a foundational part of my political development, and are why I felt it was important to engage with this book and the uncomfortable history it reveals. The task of dismantling white supremacy rests on the shoulders of those who benefit most from it. It’s on us to confront racist, white supremacist white people who assume they can count on us to smile along or stay silent when they step out of line; it’s on us to ditch that poisonous “color-blind” worldview and understand the ways in which race, identity, and political/social power intersect; it’s on us to publicly, materially, enthusiastically, and genuinely support people of color, to confront and interrogate our own internalized racism and learned prejudices without expecting people of color to educate us.

It’s on us to protest side by side with people of color against this racist, fascist, xenophobic regime. When the cops show up, it’s on us to recognize that no matter our specific identities, they will see us above all as white women, and this affords us a vast measure of safety and privilege. We must understand that it is up to us to put our bodies on the front lines to provide cover for those who are under greater threat. It’s on us to do that work, to shut up and listen, to make space for marginalized voices and recognize when we’re veering into performative, self-serving, or otherwise hollow allyship.

The entirety of that 53 percent of white women didn’t vote for Trump because of “economic anxiety;” some of them were voting to uphold an ancient, bloody order, and those sins cannot be forgiven. We need to educate ourselves, and perhaps even more importantly, to educate our children. Mothers of Massive Resistance shows how effective white women’s historical efforts to influence the school curriculum in favor of their own views have been; we’ve done it before, and now we must do it again to ensure that the next generations grow up learning about the uncomfortable, violent, imperialist history of this nation. There have always been moderate, liberal, and radical white women who push back against white supremacy, but as the current state of our nation makes clear, we’ve been far less successful than we could be, and that failure has resulted in decades of unfathomable suffering.

McRae’s book shines a harsh light on our status as collaborators and progenitors in the mainstream white-supremacist movement, and is essential reading for any white woman who seeks to understand our history—and our responsibility to those we’ve failed. White male faces dominate the discourse around the way violent white supremacy has spilled into the mainstream, but lest we forget, there were white women in Charlottesville, too—and while many of us marched alongside Heather Heyer, some of them were there to continue the work their foremothers began. We cannot dismantle what we refuse to confront. White women, we have work to do.

*Aaron is a pseudonym to protect the person’s identity.

_______________________________

Website: http://twitter.com/grimkim

Kim Kelly is a writer, editor, and radical political organizer based in New York City. She’s currently an Editor at Noisey, VICE’s music and culture channel, and also contributes to various publications, including Al Jazeera, the Guardian, and Teen Vogue. Follow her @grimkim

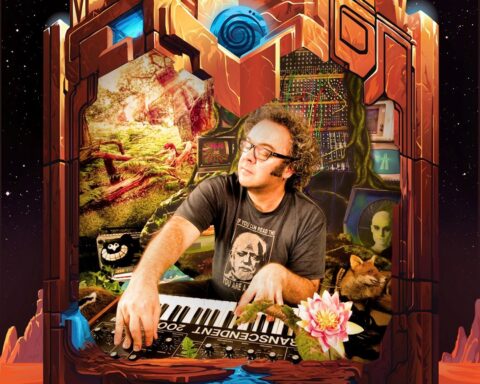

front photo: Mothers of Massive Resistance book cover (Photo credit: Oxford University Press)

article source: bitchmedia