written by Abigail Susik

As the omicron variant sweeps through American communities, many of our workplaces and institutions are grinding to a halt. With nurses, teachers and other essential workers getting ill or quarantining, we are facing disruptions at schools and in hospitals. Some employers are seeking stopgap measures, trying to hire rapidly to fill open jobs, begging for community volunteers to help keep things running and even lowering requirements for substitute teachers to get people into school buildings.

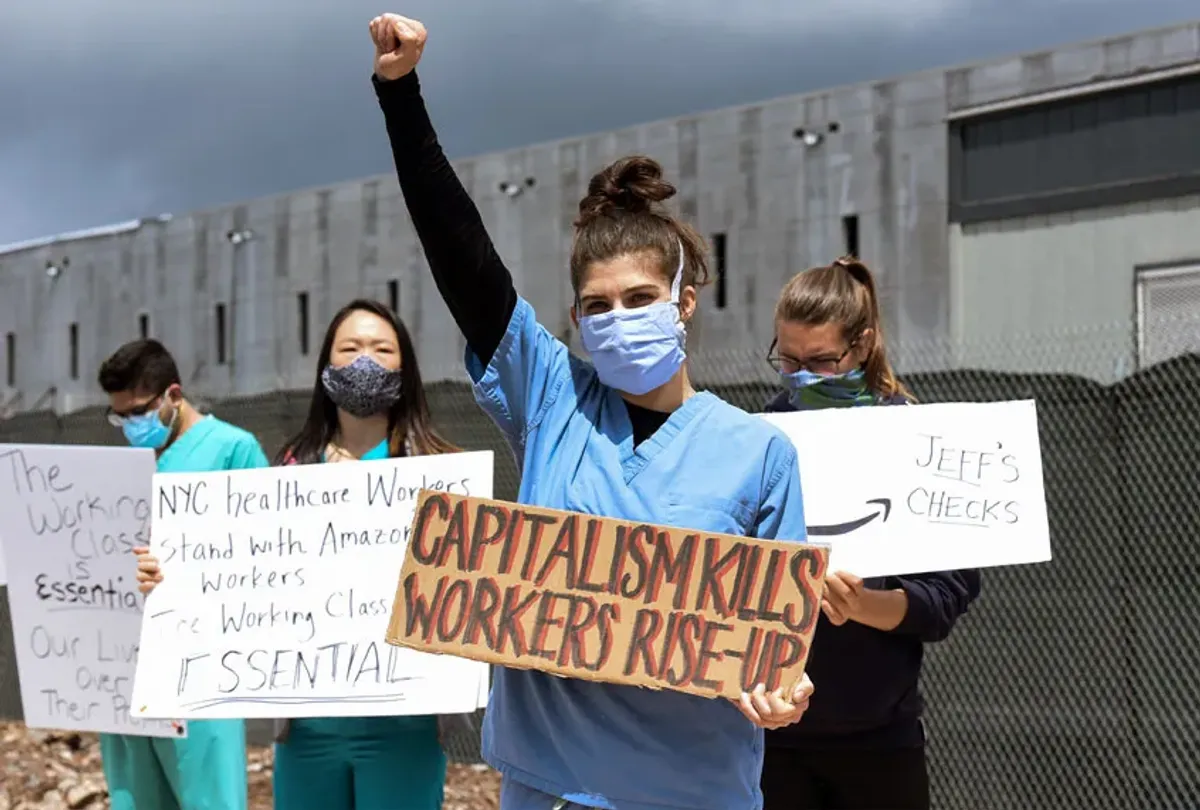

Can this be a moment for workers to demand more from shorthanded employers, whether that be higher pay, more remote work options, hazard bonuses or needed personal protective equipment to lower health risks? And how can gains gleaned in this moment be retained and even surpassed in a post-pandemic future?

Past labor shortages caused by extraordinary circumstances in other places may offer lessons. For example, in the aftermath of World War I and the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, a labor shortage and strike movement in France created conditions for envisioning transformative change. French workers seized the opportunity to pressure employers as well as the state, ultimately succeeding in changing that nation’s labor code and inspiring a growing youth rebellion against work — led by a group of young veterans who called themselves “Surrealists” — that would aim at even more radical changes.

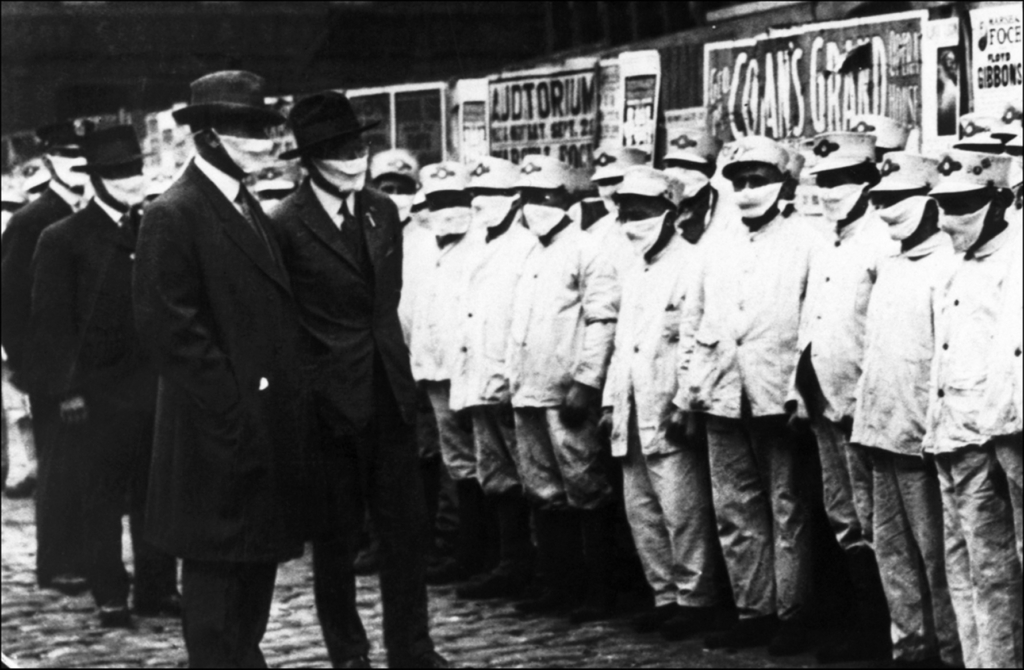

During World War I, France faced a labor shortage because of the mass mobilization of soldiers and the steep military and civilian death toll of the war. With a dearth of workers, France recruited and, in some cases, conscripted immigrant workers from the French colonies of Algeria and Morocco, Spain and elsewhere, who labored to support the war economy. But the onset of the influenza pandemic in 1918 exacerbated the labor shortage because of several conditions, including the large number of maimed veterans unable to work after the war, a low birthrate and the massive pandemic death toll.

To mitigate the labor shortfall and regulate wages, the French government accelerated the supervised immigration of mostly male workers from its empire and other nations, and, in some cases, it re-incentivized work for French women, even amid fears about declining natality.

Despite these efforts to reduce the labor shortage and keep wages artificially low during a period of rapidly rising postwar inflation, the shortfall of workers persisted. Perceiving an opportunity to gain leverage, workers organized and fought for a shorter workday and higher wages.

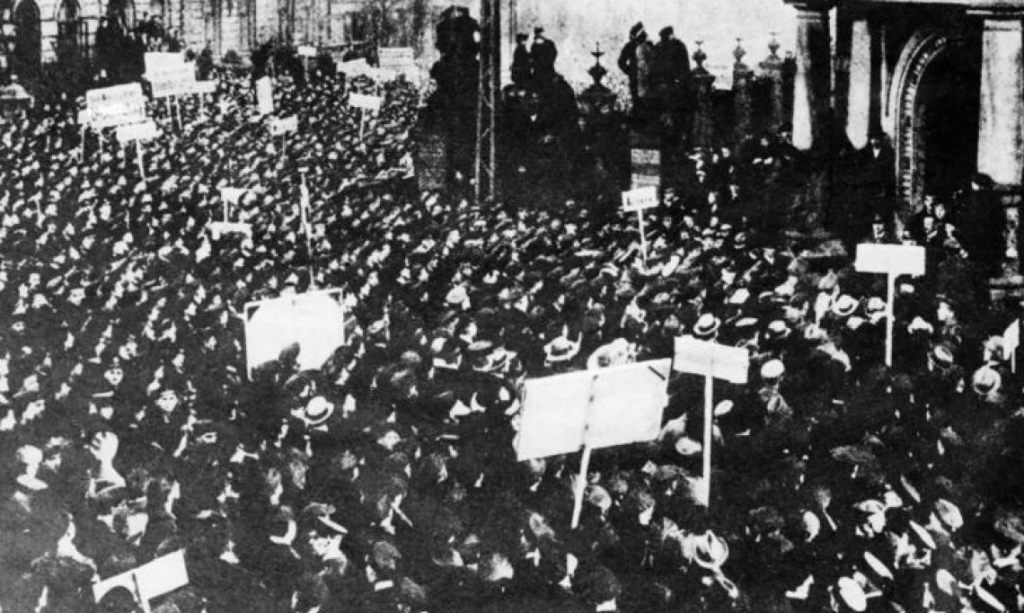

In a concentrated period between 1917 and 1920, French citizens ignited a protest movement in which millions of workers across sectors participated in organized and wildcat strikes, sabotage actions, walkouts, slowdowns and absenteeism.

As a result, the French labor force soon succeeded in winning a major demand: the enactment of the eight-hour workday by Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau in 1919. By comparison, it took the United States two more decades to institutionalize the eight-hour day and five-day workweek, with the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1940.

However, not all French workers were satisfied. Many employers refused to comply with the new eight-hour law, and as pandemic conditions waned and the labor shortage eased slightly in the mid-1920s, dissatisfaction remained palpable. Workers wanted higher wages (there was no legal minimum wage yet), the “English week” (Saturdays off, the precursor to the “weekend”) and improved conditions. Their struggle came to a head in 1936, when nationwide strikes resulted in the Matignon Agreements, which implemented significant wage increases, the 40-hour workweek and the country’s first paid holidays.

But some people had a radically different vision. In 1924, a group of young artists, writers and intellectuals, many of whom were veterans of the war, formed a cultural movement in Paris called “Surrealism,” soon declaring a “war on work” meant to battle wage-labor exploitation and what they viewed as the cult of the work ethic. In 1925, they emblazoned the cover of their journal “Surrealist Revolution” with a declaration of collective work refusal. In 1929, one member, André Thirion, penned “Down with Work!,” a powerful manifesto that echoed the 19th-century utopian socialist Charles Fourier in its demand for the essential human right to “refuse work” whenever desired.

Workers were badly needed in France’s postwar reconstruction, but the French Surrealists, most of whom were white men with some college education or professional training, attempted to abstain from further participation in what they saw as a corrupt system for workers across race and class sectors.

Disgusted by the nationalistic belligerence of wartime France that had resulted in mass death, they rallied behind the idea of a “big quit” — a radical refusal to participate in the French economy. Yet, instead of the temporary solution of voluntary unemployment, in which the worker bides time until finding a better job or higher wages, Surrealists proposed something more extreme: permanent strike.

The notion of permanent strike, or lifelong withdrawal from the workforce, meant a lifestyle of precarious labor, or what is known today as “gig work.” Their radical and utopian demand pushed up against the limits of the practical. Most Surrealists could not afford to live without earning income. Nevertheless, many deserted careers and, on principle, worked barely enough to survive. Whenever possible, Surrealists attempted to resist the allure of consumerism, believing that excessive consumption was the flip side of capitalism’s drive toward production.

For the Surrealists, the system of wage labor was historically linked to the violence of nationalism and imperialism. In 1925, they proclaimed, “We do not accept the laws of economy or exchange, we do not accept the slavery of work, and on an even wider scale we proclaim ourselves in revolt against history.”

The Surrealist goal of the permanent strike was not to pressure the boss, nor to instigate reforms, but to undermine the foundations of the capitalist nation-state altogether. This extreme position presaged (and, in some cases, influenced) the broader work refusal that characterized various youth and activist countercultures going forward in the 20th and 21st centuries — including beatniks, hippies, gutter punks, purportedly “lazy” millennials, today’s anti-work advocates and the current “lying flat” movement in China. If certain anti-work countercultures are primarily pursuing, in the words of 19th-century communist writer Paul Lafargue, “The Right to be Lazy,” the Surrealists were wage labor abolitionists who sought a utopian post-work system.

Today’s labor market differs from that of post-World War I France in almost every imaginable way, and the ongoing pandemic is playing a distinct role right now. Nevertheless, a comparison of our workforce shortages with those of a century ago is telling. The “Great Resignation” of 2021 has been likened to an “unofficial general strike.” For workers, at least, such frictional unemployment and aspirational job switching can be a good thing. Taking stock of the 1917-1920 French labor crisis and the Surrealist “war on work” provides a provocative example of how organized workers can escalate their advantage and bolster their morale during and after a shortage — and how oppositional countercultures can imagine a totally different future for workers.

______

Abigail Susik, who wrote this piece for the Washington Post, is an associate professor of art history at Willamette University and author of “Surrealist Sabotage and the War on Work.”

source: https://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/

READ ASLO