Branded as terrorists by President Erdoğan’s hardline regime, LGBTQI+ people in Turkey are finding ways to express themselves and build solidarity, writes Tuğçe Özbiçer.

As my friends and I climb the old staircase to a bar in Istanbul’s vibrant Taksim district, I’m surprised to hear the establishment’s name. I thought Şahika had shut down but it seems my friends had just stopped going. ‘Queer managers took over,’ they explain, ‘so we have all migrated back!’

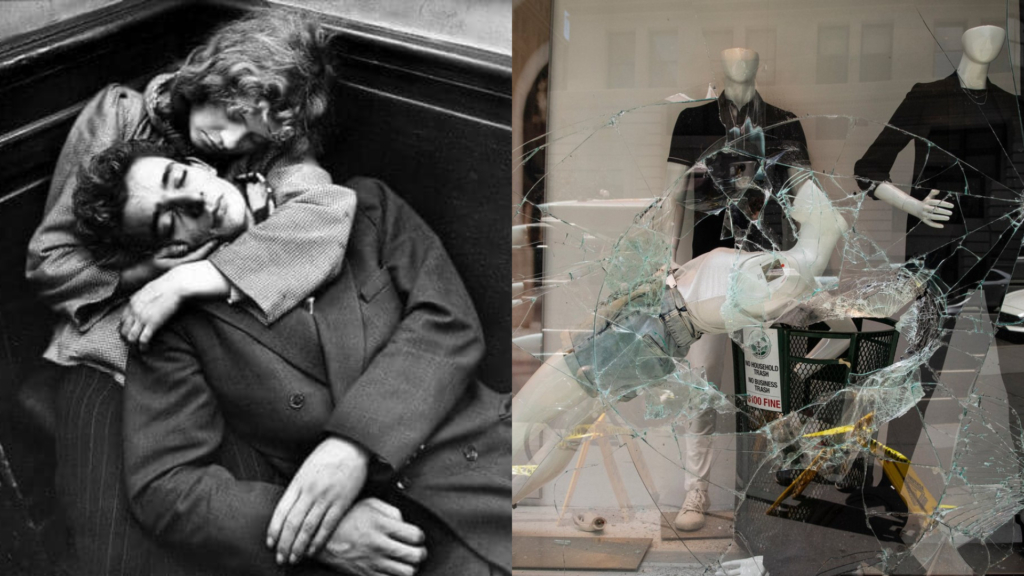

Passing familiar faces in colourful outfits, laughing and kissing, we enter a room overflowing with life. Akış Ka, a drag artist, performs to a cheering crowd. People from the LGBTQI+ community come here to be with each other as they are, true to themselves, despite the hate that the government spreads.

In February 2021, president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan told the nation: ‘LGBT – there is no such thing.’ There are continuous attempts to exclude the LGBTQI+ community, as well as the feminist movement, from the public sphere. But in underground spaces such as Şahika, it’s clear that Erdoğan is wrong.

Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been ruling Turkey for almost two decades now. Since a sweeping electoral win in 2002, the AKP has slowly and meticulously made the transformation from being a conservative rightwing party to becoming an authoritarian far-right regime. When Erdoğan was re-elected as president in 2014, winning 51 per cent of the vote, the most populist chapter of his leadership began. It has been marked by attacks on minority groups and increased suppression of the political opposition in academia, media and civil society.

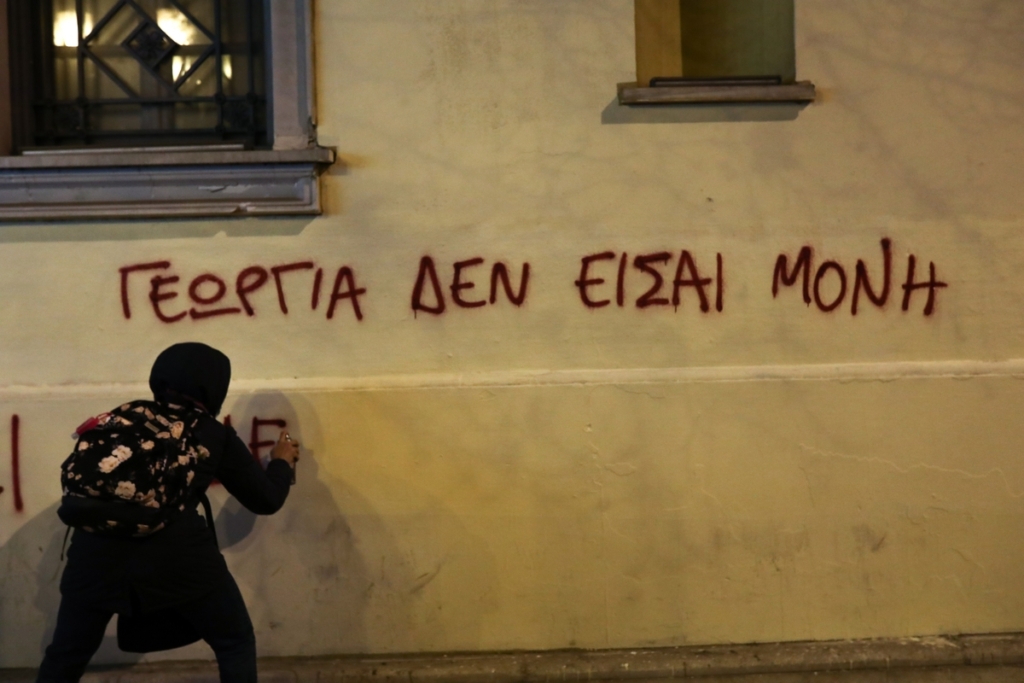

Istanbul’s annual Pride March has been running since 2003 and has been steadily growing in popularity. In 2013, almost 100,000 people attended and by 2014 it was the biggest LGBTQI+ event in Turkey’s history. But in 2015 Pride was officially banned by The Istanbul Governor’s Office, citing security concerns. Although it still takes place, the event is brutally attacked by police every year. In 2021, officers fired tear gas into the crowd and around 20 people were arrested.

Making minority groups ‘enemies’ is a useful tactic for Erdoğan as he deepens his grip on power. It’s a strategy that has proved effective in the past. ‘AKP has been systematically violent towards Kurds, Alevis, working-class people and women. The LGBTQI+ community is the easiest to attack. In a way it is mathematical: individuals from all social, ethnic or class backgrounds can be united by homophobia and transphobia,’ Akış Ka says.

Crucial solidarity

In the face of increased oppression, solidarity has grown, often fostered in spaces like Şahika. This solidarity is crucial for the LGBTQI+ community in Turkey where discrimination often begins within the family and expands into all areas of the society.

This solidarity appears in different forms: listening to each other’s troubles, being there for support when someone has suffered from violence, or sharing creative work to help queer groups and individuals to reach a bigger audience.

‘The solidarity in the LGBTQI+ community made me the person who I am today,’ says Akış Ka, whose stage name comes from the word ‘Akışkan’, meaning ‘fluid’ in Turkish.

Akış Ka points to the core of solidarity and its importance on an emotional level: ‘It is, first of all, being together. And crying together. It means the world. Crying with someone, for the same thing.’

Stronger ties have been made with other social justice movements. Co-operation between the queer movement, political parties, and human rights organizations increased in 2013 when anti-government protests swept the country. These coalitions have made it easier for the LGBTQI+ community to voice their concerns and demand recognition and acceptance. ‘Suddenly we were labelled a “threat” because we had so much support and we were very visible. Erdoğan’s conservative supporters were scared their children would also come out as gay!’ Akış Ka comments.

‘Absurd and scary’

In 2021, a six-month-long student protest movement calling for the democratic election of a university rector turned into a fight for LGBTQI+ rights, with many detained and arrested for offences including ‘displaying rainbow flags’.

Students at Boğaziçi University opposed the appointment, by Erdoğan himself, of rector Melih Bulu. One of the AKP’s parliamentary candidates in 2015, Bulu had remained a close ally of the party and the President.

‘Those who joined the protests are not students,’ said Erdoğan in January 2021. ‘This is something involving terrorists.’

Hazar is an activist and artist from Istanbul and a former student of Boğaziçi University. She was one of the founders of BOUN Art Collective (Boğaziçi University Art Collective) which, as part of the protest, organized a campus-wide exhibition displaying over 400 works submitted by artists across the world.

One piece entitled ‘Yılanı Güldürseler’ (To make the serpent laugh) showed a picture of Kaaba, the most sacred site in Islam, with various LGBTQI+ solidarity flags in each corner. Hazar says that conservative students posted a photo of it on Twitter, saying ‘it is insulting Islam’.

Erdoğan divisively commented: ‘We will lead our young people to the future not as the LGBT youth but as the youth that existed in our nation’s glorious past.’ Following him, interior minister Süleyman Soylu tweeted that ‘the government would not tolerate the LGBT perverts who attempted to occupy the rector’s office’.

Hundreds of students were detained, including Hazar and six others from the Collective. They were charged with ‘provoking the public to hatred and hostility.’ Hazar, who now lives in Berlin, was put on trial – a process she describes as ‘absurd and scary’.

‘The judge asked me if I’m serving for LGBT. As if being LGBTQI+ means that you belong to some kind of illegal organization that you could serve for!’ explains Hazar. She was sentenced to house arrest for a month.

The finger of blame

‘Attempts to present the LGBTQI+ movement as a terrorist organization have a lot to do with the state’s increasingly militarist, transphobic and homophobic ideology,’ says lawyer and activist Eren Keskin, who is the founder of the Legal Aid Office Against Sexual Harassment and Rape in Detention.

This terrifying trend is led by the President but echoed by many others, including anti-LGBTQI+ ministers and corrupt media platforms that continue to spread hate.

LGBTQI+ people have even been made scapegoats for the Covid-19 pandemic. In April 2020, Ali Erbaş, the head of Turkey’s Religious Affairs Directorate, delivered a sermon in which he said that homosexuality caused disease. ‘Let’s come and fight together to protect people from this kind of evil,’ he said. President Erdoğan backed him up, stating that Erbaş was ‘totally right’ in what he said.

Erbaş was also massively influential in relation to Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention on Combating Violence Against Women in March 2021. As the most comprehensive agreement to tackle gender-based and domestic violence, it bothered some conservatives because it recognized the abuse of a husband, boyfriend, father or a brother.

According to Keskin, ‘Erdoğan’s government and its supporters are terrified by the feminist and LGBTQI+ movement because both are bravely fighting against so-called “traditional Turkish family values”.’

At least 280 women were murdered in 2021 according to the ‘We Will Stop Femicide Platform’ – the majority killed in their homes. In 2020, Turkey was ranked by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association as the second worst place in Europe for LGBTQI+ rights out of 49 countries. Turkey was also ranked as having Europe’s highest trans murder rate in 2016.

Space for expression

‘Most of my clients who have experienced human rights violations are trans people. Even when they are wandering the streets, police come to them and charge them with “polluting public areas” or “abusing public spaces”,’ says Keskin.

In prison trans people face a double punishment; if they haven’t had gender-affirming surgery they are held in solitary confinement. Although it is legal to apply to undergo gender reassignment whilst in prison the Turkish state will usually refuse, illegally claiming that ‘gender-reassignment surgery is a type of plastic surgery’.

In 2018 Buse Aydin, a trans woman inmate, applied and went through all the necessary processes to get surgery. She ended up on a 38-day long hunger strike for the approval of a human right that’s covered in the 8th and 14th articles of the European Convention on Human Rights. Even after that, the Ministry of Health refused to cover the costs of the necessary surgeries. ‘After all Buse was forced to go through, she cut her penis in solitary confinement in 2019. With the incredible work of women’s and LGBTQI+ organizations, she finally had her gender-affirming surgery and the state covered the costs. She is happy now, recovering,’ says Keskin, Buse’s lawyer.

Despite all the oppression that Turkey’s LGBTQI+ community has been facing, its existence is more visible than ever. Asserting themselves in various state and non-state spaces, queer people continue to resist, especially through creative works and a growing arts and culture scene in big cities.

‘We’re expressing ourselves through art, music, performance… We’re telling our own empowering stories out loud, writing our own history. If we don’t, then there will be no memory or evidence of a LGBTQI+ community in Turkey,’ says Akış Ka.

‘Our stories inspire and empower others. The state doesn’t support us, but what can they really do? As long as the world keeps running, we’ll be here. If we lose our hope for equality, justice and freedom, there is nothing to hold on to.’

Turkey’s LGBTQI+ community is more resilient than vulnerable. And, the fight will go on.

_____________

Tuğçe Özbiçer is a journalist from Istanbul. She worked for several Turkish left-wing newspapers before moving to London in 2020, Due to the increased oppression of the media in Turkey. She covers mostly LGBTQI+ issues, women, arts and culture, and human rights stories.

This article is from the May-June 2022 issue of New Internationalist.