Lots of people are reading Rodrigo Nunes’s Neither Horizontal Nor Vertical this summer, including some people to whom I recommended the book, and so I thought I’d do a post about it.

When I was writing my review of Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn, I thought that I would end by comparing the Bevins and Nunes. Like Bevins, Nunes’s theoretical tract is a “response to the cycle of struggles that began in 2011” but unlike Bevins, Nunes does not think that the failures of this cycle of struggles can be attributed to ideology alone. While he does offer a critique of “horizontalism,” like Bevins, he recognizes that this ideology is, in part, a response to certain underlying material conditions that remain, for better or worse, unavoidable. The nature of capitalist society has changed and so, therefore, has the nature of class struggle. Leaving aside whether this would be desirable or not, attempting to turn back the clock to an era in which unions and parties and other formal organizations mediated class struggle is itself ideological, an expression of left melancholy that needs to be overcome.

So what is it that has changed? The place to look for answers is in the heart of the book, “Elements for a Theory of Organisation 1.” As Nunes writes, “the idea of horizontality” emerges for three reasons: “an increased awareness of the interconnectedness brought about by capitalist globalization; the discovery of the organizing and mobilizing affordance provided by the internet; and the inspiration coming from autonomous movements in the Global South, especially the Zapatistas in Mexico and those that emerged in Argentina in the wake of the 2001 crisis.” In other words, while the “idea of horizontality” may be ideology, what it responds to are very real changes in the nature of society: globalization, information technology, and new form of class struggle emerging in response to these. Note how different this account is from Bevins, who attributes horizontalism—or the idea of horizontality—to ideology alone. As he writes later in the chapter:

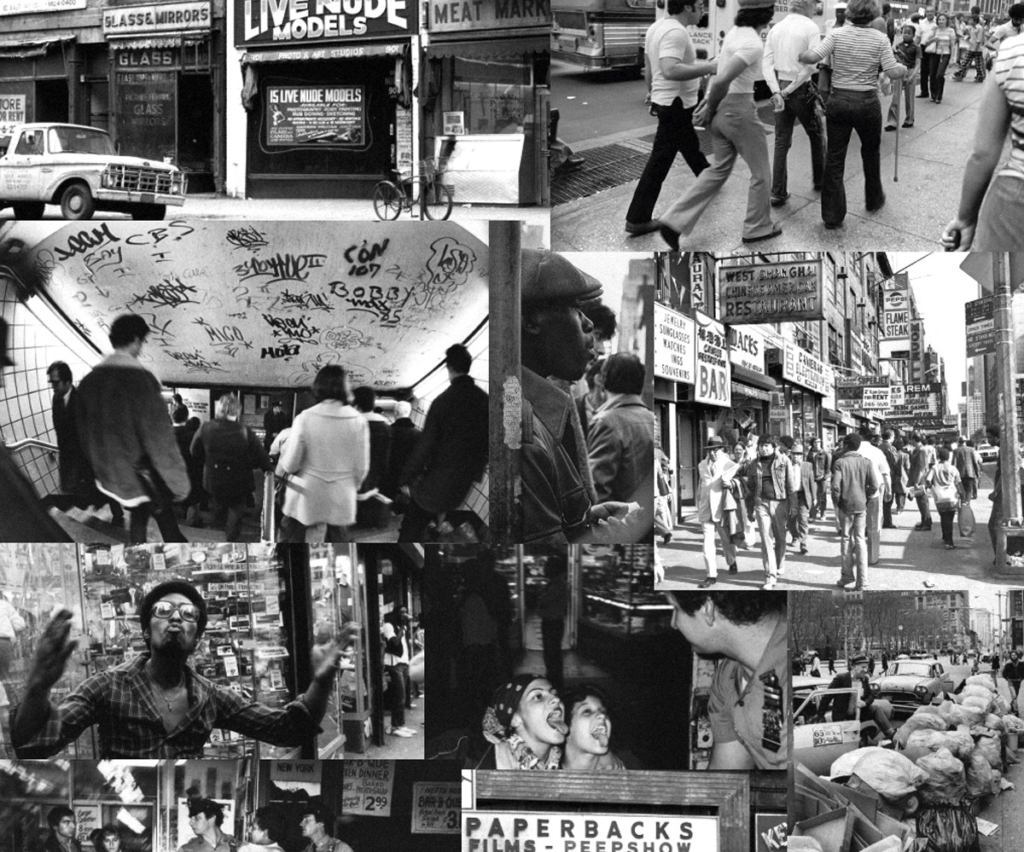

Today’s revolts emerge from a conjuncture marked by the convergence of four historical trends that, at least for now, appear irreversible. The first is the increasing mediatisation of everyday life, and specifically the use of digital platforms that generate an enormous potential for what Manuel Castells dubbed “mass self-communication.” The second is the vertiginous drop in organising costs resulting from that, which enables complex collective coordination on a scale that in the past could only have been achieved through mass organisations. The third is the crisis of the “post-political” centrist consensus dominant in most countries since the end of the Cold War, which has intensified a long-running loss of confidence in liberal democratic institutions across the world. The fourth is the decline, in membership as well as political relevance, of most mass organisations that played a central role in convoking and organising popular struggles in the twentieth century.

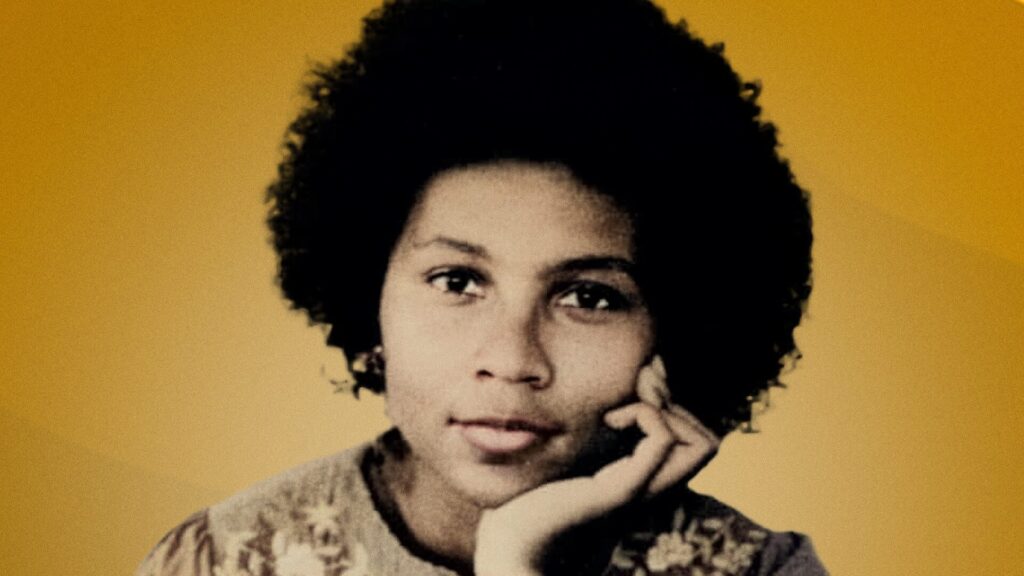

Only reason 3 is a matter of ideology—the others are material changes in the nature of contemporary life that are irreversible except through other material changes. Fighting against the ideology of horizontalism without addressing these underlying material conditions is quixotic because these new forms offer both potentials and drawbacks. The easiness of networked organizing outcompetes formal organizations time and again, and therefore one must accept that, for the time being, this will be a big part of the mix, even if one imagines, as Nunes does, an important role for formal organizations. The result of this recognition is that Nunes suggests we stop thinking about organization as formal organization alone but look at “organisational ecology” which includes both formal and informal organization. In fact, Nunes argues that since the 1960s and 1970s this ecological perspective has been implicitly adopted by movements where a leading formal organization was lacking, such as “Autonomia” or “the movement of ‘77” in Italy and the Gay and Women’s Liberation Movements.

This brings us to some of the most important points of the book, with regard to contemporary debates about organization. Today there is a tendency to treat organization as a quantity which can be measured—organization is something which class struggle today lacks, either in whole or in part, and therefore the problems confronting us are problems of “disorganization.” But for Nunes organization is just what there is, and what some people describe as disorganization is simply a different form of organization. This is a point that has been made many times before, including by me. What people describe as spontaneous, reflexive, and disorganized is often, in fact, quite organized. Riots don’t lack organization, though they do typically lack formal organization. Contemporary movements are, in fact, a kind of fractal—when you zoom in on the disorganization of the riot what you find are, in fact, planned, conscious actions that merely appear disorganized in aggregate. This insight applies the other way, too. When one examines the behavior of a formal organization, what often appears highly organized in aggregate is often quite spontaneous, unplanned, or chaotic when one zooms in, since all kinds of decisions taken within organizations are done so informally. “Spontaneity” is therefore a particularly problematic concept.

Nunes also offers a criticism of another concept, “self-organization,” that is often used by the ultraleft to describe the power of informal organization. But what is the self of self-organization? What we call self-organization is often not really very self-organized but rather in response to some kind of other-organization. In class society, and in struggles against it, there is no real self-organization, since that would imply full autonomy for the self-organized group when, in fact, what we describe as self-organization is a reaction to heteronomy—to the fact of being organized by bosses, cops, unions, and parties.

The critique of self-organization that Nunes offers is gotten at by way of the discourse of cybernetics, and particularly second-order cybernetics. Cybernetics is, in some senses, a study of self-organization. It defines animals, people, machines, and even organizations by their capacity to act on and regulate themselves through circular causality. But any organism deemed self-organizing is always in relation to whatever is outside the self, from which it derives energy, resources, etc. Even though the human body self-regulates it isn’t really self-organized since it is partly produced by forces outside itself, hence second-order cybernetics. This is a useful framework and one of the best aspects of the book is the way it takes ideas from cybernetics and shows their utility. As much as this discourse has been used by capitalism to naturalize economy and society, there are some important truths contained within it, and for better or worse, we can’t get away from the language of “emergence” when it comes to describing society and its class struggle. Without the notion of emergence, it becomes hard to understand how things happen without anyone intending them. Though the Hegelian dialectic is another way to get at this, “emergence” is here to stay and helps explain how movements always surprise us and how they unfold in ways that are beyond the control of individuals

In a subsequent chapter, I will offer some criticisms of Nunes, and indicate some of the problems with his approach.

I wanted to indicate why I think the Nunes book is important, useful, and underrated. Now I want to spell out some of my criticisms of the book.

My first criticism is that I think the account which we get in the book of the emergence of the “network paradigm” lays the emphasis too much on technological change, and the internet in particular. Of the four causes that Nunes gives for this emergence—information technology; cheaper organizing via information technology, the crisis of centrism, and the waning of workers’ parties and unions—the fourth is, in my view, the most important, whereas Nunes’s book lays emphasis on the first two. (I should add that I think 1 and 2 are the same, and 3 not a real thing). But we can easily deduce that the fourth is the determinative cause since the examples he gives of “organizational ecology” date from the 1970s and not the 1990s. If the ecological view emerges with the Women’s and Gay Liberation Movements or the “area of Autonomy” in Italy in 1977 and not the networked, alter-globalizing Zapatista Liberation Army, then we cannot attribute it to digital technology primarily. The crisis of the parties and unions—or what Endnotes and others have described as “end of workers’ identity” of the “end of the workers’ movement” or “programmatism”—emerges much earlier than digital technology, and is therefore determinative.

Furthermore, some of what Nunes attributes to the network paradigm has been a consistent feature of class struggle for as long as we have examples. Informal organization—aggregate action—has always been part of the mix, and we can find recognition of this “self-activity” in Marx, Luxemburg, and others. Nearly every revolution has begun as a consequence of informal organization with formal organizations playing catch up. Since the 1990s, digital technology has acted as a multiplier for this kind of informal organization, but the decline of formal working-class organization is, in my view, far more consequential. Adopting an evolutionary framework, Nunes argues that informal organizing now out-competes formal organization as a result of the low levels of initial investment digital technology affords—anybody can, potentially, reach millions with a single tweet or TikTok. In a fascinating moment in the text, Nunes suggest that, rather than an era without vanguards, digital technology has allowed nearly anyone to become a vanguard, such that the leadership function, rather than having disappeared, has been distributed more widely. Anyone who has participated in contemporary social movements will recognize the truth of this assertion, even if when, we trace things back to their origins, we often find the actions of vouched groups rather than scattered individuals. Aggregate action (informal organization) and collective action (formal organization) are always co-present. It’s not that intentional, deliberate action has disappeared—in fact there is more of it than ever, it’s just that now it’s in the hands of more people.

In assigning relative weight to these various causes, we should place emphasis, however, on the inability of formal organizations to “get the goods” and downgrade the lower investment allowed by digital technology. The affordances of the digital are not, in this regard, all that different than print—or graffiti, for that matter—which is why we see the “ecological” paradigm emerging in the 1960s and 1970s and not the 1990s. In the era of the classical workers’ movement—let’s date it from 1871-1968, for convenience—the unions and parties which were able to assert partial leadership over social movements did so because they were able to deliver tangible benefits to participants through bilateral negotiations with the state and capitalists. But today we live in an era in which, to put it bluntly, due to weakening growth, elites are much less willing to negotiate. There is no longer a compromise position and class struggle has become much more zero-sum. As such, the fruits of formal organization are diminished as a function of investment in such organization, and it is this which explains their decline, and the preference for informal organization, not some deleterious ideology emerging from the Port Huron Statement and sent around the world. It’s not so much that informal organization has become cheaper but that everything else has become more expensive.

The other problems with Nunes’s approach might be described as formalism and monism. Nunes offers us a theory of “political organisation” and not a theory of revolution or communism. As such, its strengths (its lucidity about organisation) rest on weaknesses. In its Spinozism, it defines organization as the “capacity to act” and “produce political effects” but are all capacities and effects equal? While Nunes states that his aim is a theory of political organization rather than organization as such, it’s hard to see how his definition is specific enough to emancipatory, revolutionary, or communist organization—ie, the forms of organization we care about. Doesn’t this definition work for fascist organization as well? Doesn’t it describe the organizing forms of the state and capital? Are those not “political”? A related problem is that (revolutionary, emancipatory) political organizations are usually described and analyzed in the book without any reference to antagonist organizations. But the goal of communist organization is not just to multiply the power of such organizations but to negate the already-existing organizations by which proletarians are always already organized: the organizations of capitalism and the state. In other words, the theory of political organization we get in Nunes’s book lacks negativity and does not sufficiently distinguish emancipatory from counter-emancipatory organizations. This is because its definition of organization is formalist or perhaps functionalist but is missing “content,” missing a sense of what such organization is for, ultimately—ie, the production of classless, moneyless, stateless society. It is possible that such a society can be defined as a kind of organization but the book does not do so.

Marx’s definition of communism as a state of affairs in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” shares something with Nunes’s definition of organization as “capacity to act” but contains some additional predicates. Development is not only capacity to act but capacity to cultivate new capacities and experiences. In other words, we can’t define organization formally but must think about content, about what people want and what people are. This is something which Nunes resists, given the post-Althusserian and antihumanist theory he relies on, but I don’t think it can be avoided if we want to develop a theory of emancipatory organization.

____

SOURCE: https://jasperbernes.substack.com/p/organization-and-its-theories