Written by Harris Kalaitzidis, (MA in European Philosophy from Royal Holloway University of London) and member of Void Network. His first novel, War Machine (Estia Bookstore, 2022) was honored with the Debut Novelist Award of the Hellenic Authors Society.

Translated by Nikos Gatzikis

____________

Marxist theorist Mark Fisher (1968–2017) posed a critical question: “Are cultural resources running out in the same way as natural resources are?” (Fisher, 2009). Through an analysis of cultural production over the past fifty years, he argued that the popular culture of Western societies has ‘frozen’ in the 20thcentury, with the present characterized by timeless repetitions, revivals, and a striking lack of innovation.

According to Fisher, the 20th century was defined by the parallel development of technological and cultural forms: the emergence of new technologies allowed for formal changes in pop culture, giving it a distinct chronological “signature”(Fisher, 2009). As examples, we can consider how the synthesizer became emblematic of the music of the ’70s and the ’80s or how the ‘rough’ assembly of samplers characterized ’90s rave music.

However, from 2000 onward, this trend disappears, and technological progress becomes disconnected from cultural production: technology continues to advance in leaps, but popular culture remains stagnant, clinging to its old forms. In fact, as Fisher notes, new technologies often serve not to produce new cultural forms, but to more faithfully reproduce old ones.[1] In this way, today, technological innovations “have tended to be parasitic on old [cultural] media” (Fisher, 2009).

If Fisher diagnosed a cultural landscape trapped in an endless loop of the past,Generative AI is not just another instance of this inertia – it is its logical conclusion. I argue that applications for text, image, and sound production—such as ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Soundraw, which utilize data from human activity to generate content—exemplify the tendency Fisher identified.

To make this parallel clearer, we must first examine Fisher’s arguments more closely.

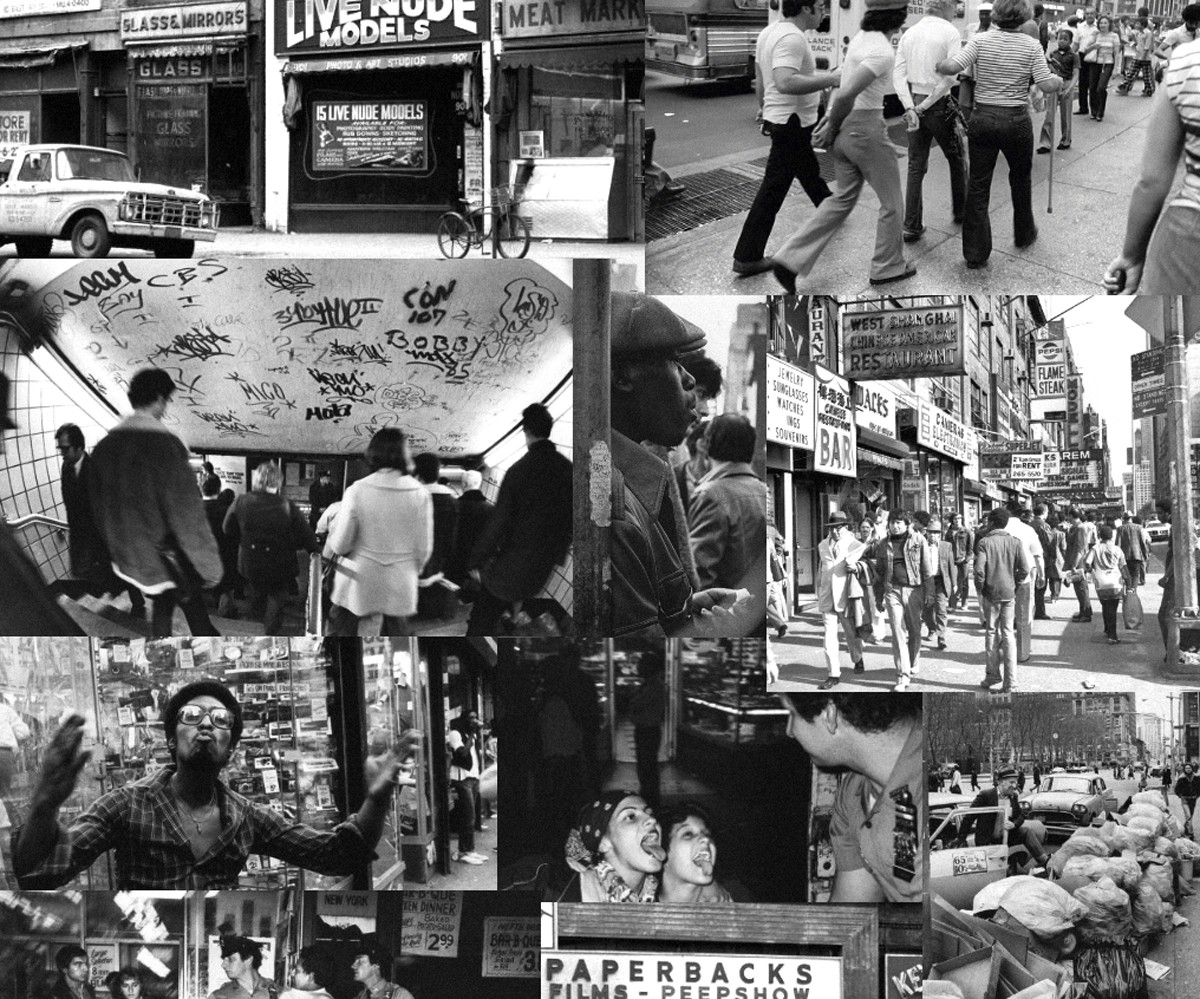

In the texts included in Ghosts Of My Life (Fisher, 2014a),as well as in his blog k-punk, Fisher argues that the Western culture of the 20thcentury was essentially modernist, rejecting the past and striving to achieve some formal innovation. Moreover, in contrast to the elitist and largely inaccessible modernism of the first half of the 20thcentury, the period from 1960 to 2000, which shaped Fisher’s aesthetic perception, was marked by the emergence of a “popular modernism” with mass appeal (Fisher, 2014b). The examples Fisher usesare mainly drawn from British music: 1960s psychedelic rock, 1970s punk, 1980s post-punk, and 1990s rave.

In contrast to this era of unprecedented innovation, the popular culture of the 21st century has abandoned modernism. Cultural forms no longer rebel against the past, but embrace it and repeat it. Thus, the“nostalgia mode” of postmodern capitalism (a term by Fredric Jameson) exhibits a “formal attachment to the techniques and formulas of the past, a consequence of a retreat from the modernist challenge of innovating cultural forms” (Fisher, 2014a, p. 11).

The examples that can be used to support this idea are endless. Fisher points to the disappearance of the ‘retro’ genre in music, a category that has stopped making sense, since, today, everything is somewhat retro and essentially timeless. Thus, Adele and Amy Winehouse—whose “recordings are saturated with a vague but persistent feeling of the past” (Fisher, 2014a, p. 14)—were not considered retro, but entirely contemporary.

Fisher also refers to the inability to identify the distinctive “sound” of the 2000s or 2010s, as well as the sterile appropriation of rave by bands like the Black Eyed Peas (Fisher, 2014a, p. 180) or mod by groups like Blur and Oasis. Rather than genuine tributes, he argues, these repetitions were “confidence tricks which borrowed yesterday’s inventions and half-heartedly passed them off as today’s swagger” (Fisher, 2014b). In the 2020s, one need only look at Hollywood, which increasingly resembles an Ouroboros, endlessly regurgitating its own past through sequel after sequel, spin-offs no one asked for, and countless remakes.

But how can we explain the disappearance of popular modernism in the 21st century? Why has pop culture stopped drawing on the creativity of technological advances? According to Fisher, the main reason is the transition of Western societies from the social democracy of the post-war period (welfare state, relative safety) to the neoliberal era ushered in by Thatcher and Reagan (expansion of the market sphere, dominance of managerial logic). This shift coincided with the transition from Fordist capitalism (stable employment in a specific space with limited hours) to today’s post-Fordist capitalism (precarious work with flexible hours, work that you take home, pervasive anxiety).

This transition brought significant changes to the production and consumption of art, and Fisher argues that these changes are responsible for the stagnation of contemporary pop culture. Regarding production, neoliberal capitalism “has gradually but systematically deprived artists of the resources necessary to produce the new” (Fisher, 2014a, p. 15). With the erosion of the welfare state, free tertiary education, and both private and public spaces (low rents, squats), the “indirect source of funding” that enabled experimentation in 20thcentury pop culture has disappeared. Today, most artists are pressured “toproduce something that [is] immediately [profitable]”and thus turn to “cultural products that resembl[e] what [is] already successful” (Fisher, 2014a, p. 15).

At the same time, in terms of consumption, the audience of pop culture ends up desiring the reproduction of familiar forms, demanding ‘more of the same.’ The neoliberal condition of general uncertainty compels usto seek security in “established” cultural expressions, while the “besieging of attention” imposed by the technologies of communicative capitalism makes us “demand quick fixes,” such as the “easy promise of a minimal variation on an already familiar satisfaction” (Fisher, 2014a, p. 15). In this way, Fisher argues, neoliberalism is the primary mechanism behind the freezing of pop culture.[2]

I feel that Generative AI represents the culmination of the creative enervationthat Fisher diagnosed. Artificial intelligence is anachronistic by nature, inherently bound to the cultural production of the past. Its function is to metabolize the data of human activity (literature, painting, music) in orderto produce combinations of words, pixels, and sounds that satisfactorily respond to a given prompt.

Indeed, AI is very capable. ChatGPT can write a good paragraph “in the style of Woolf,” Midjourney can generate a good image “in the style of Monet,” So-VITS-SVC can even make songs with Tupac’s voice. But they cannot revolt. They cannot rupture. They cannot escape the weight of the pastand bring something new. Paraphrasing Fisher, we might say that “the law of [AI] is that everything comes back” (Fisher, 2014b), whether it be writing styles, artistic techniques, or even the dead themselves.

Thus, if AI artists are selling images online, if Kanye is releasing AI music videos, if Hollywood is considering using chatbots to write scripts and if inspired dissertations are already being drafted by ChatGPT, the result is utterly void. The only thingAI can do is ingest what has already happened and regurgitate it as formula, as undead forms that refuse to disappear. In this sense, Generative AI is the perfect realization of capital’s necromanticdream: culture that consumes itself endlessly, resurrecting the past while preventing the emergence of the new.

It follows that debates about AI’s “intelligence” or “consciousness” are absurd. The fact that we recognize our own reflectionin AI says more about us than it does about it. The ability of AI-generated self-help books or young adult fiction to selldoes not mean that AI writes ‘like a human’ – it means that, for decades, many humans have been writing, reading, and thinking like machines.

Thus, when we speak of AI’s (present or future, actual or virtual) “consciousness,” this tells us nothing about the algorithm’s“intelligence”, but insteadreveals how much we have mechanized our thinking, how much we have distancedourselves from our own bodies, our own experiences, andour own creative capacities, to the point that we now see our image reflected in binary code.

The moment we disconnect consciousness from the emergence of the new is the moment we surrender to the sterile timelessness of capitalist non-sense.

_____________

Haris Kalaitzidis

References

Fisher, M. (2014a). Ghosts of my life: Writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures. Zer0 Books.

Fisher, M. (2014b, January 5). Going overground. k-punk. https://k-punk.org/going-overground/

Fisher, M. (2009, April 15). Running on empty: The lack of innovation in pop music suggests that we are experiencing an energy crisis in culture. New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/long-reads/2009/04/culture-technology-energy-rave

[1] Fisher cites the example of HD televisions, where “we see the same old things, but brighter and glossier” (Fisher, 2009). In the 21st century, we might consider how Hollywood uses CGI to make aging actors appear younger (e.g., Robert De Niro) or to resurrect them entirely (e.g., Carrie Fisher).

[2]If Fisher’s analysis has a limitation, this ishis tendency to overwhelmingly focus on neoliberalism without situating it within the broader tendencies of capitalism and the oscillation between the contractual and the authoritarian poles of the state. As a result, and even though Fisher insists that he is not proposing some nostalgic return to social democracy, his work—or, at least, many interpretations of it—struggles to shake the sense that things ‘were better back then’, and that the main problem in today’s world is neoliberalism. I suspect this was one of the reasons that led him to take up one unviablepolitical position after another: engaging with accelerationism and left cybernetics in his youth, becoming enamoured with Syriza, Podemos, and Corbyn later on, and attacking the “neo-anarchist” tendency of horizontalism and rejection of parliamentary politics.