Void Mirror accomodates 3 articles from the mainstream press proving that the time for the Global Legalization of All Drugs has come.

He says U.S. drug policy leads to corruption of politicians and law enforcement

“Legalizing drugs is the best way to reduce drug violence.”

He says drugs should be controlled through regulation and taxation

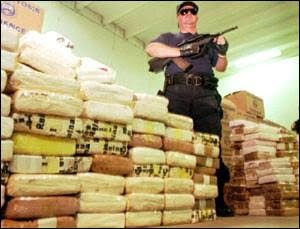

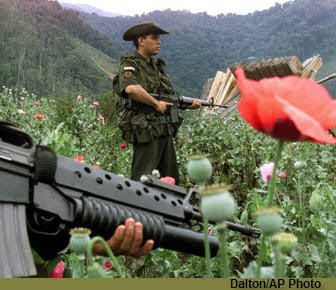

CAMBRIDGE, Massachusetts (CNN) — Over the past two years, drug violence in Mexico has become a fixture of the daily news. Some of this violence pits drug cartels against one another; some involves confrontations between law enforcement and traffickers.

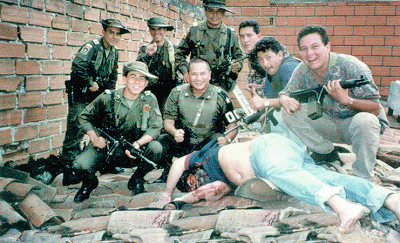

Recent estimates suggest thousands have lost their lives in this “war on drugs.”

The U.S. and Mexican responses to this violence have been predictable: more troops and police, greater border controls and expanded enforcement of every kind. Escalation is the wrong response, however; drug prohibition is the cause of the violence.

Prohibition creates violence because it drives the drug market underground. This means buyers and sellers cannot resolve their disputes with lawsuits, arbitration or advertising, so they resort to violence instead.

Violence was common in the alcohol industry when it was banned during Prohibition, but not before or after.

Violence is the norm in illicit gambling markets but not in legal ones. Violence is routine when prostitution is banned but not when it’s permitted. Violence results from policies that create black markets, not from the characteristics of the good or activity in question.

The only way to reduce violence, therefore, is to legalize

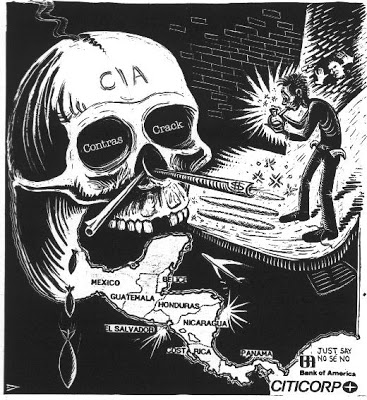

Prohibition of drugs corrupts politicians and law enforcement by putting police, prosecutors, judges and politicians in the position to threaten the profits of an illicit trade. This is why bribery, threats and kidnapping are common for prohibited industries but rare otherwise. Mexico‘s recent history illustrates this dramatically.

Prohibition erodes protections against unreasonable search and seizure because neither party to a drug transaction has an incentive to report the activity to the police. Thus, enforcement requires intrusive tactics such as warrantless searches or undercover buys. The victimless nature of this so-called crime also encourages police to engage in racial profiling.

Prohibition harms the public health. Patients suffering from cancer, glaucoma and other conditions cannot use marijuana under the laws of most states or the federal government despite abundant evidence of its efficacy. Terminally ill patients cannot always get adequate pain medication because doctors may fear prosecution by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Drug users face restrictions on clean syringes that cause them to share contaminated needles, thereby spreading HIV, hepatitis and other blood-borne diseases.

Prohibitions breed disrespect for the law because despite draconian penalties and extensive enforcement, huge numbers of people still violate prohibition. This means those who break the law, and those who do not, learn that obeying laws is for suckers.

Prohibition is a drain on the public purse. Federal, state and local governments spend roughly $44 billion per year to enforce drug prohibition. These same governments forego roughly $33 billion per year in tax revenue they could collect from legalized drugs, assuming these were taxed at rates similar to those on alcohol and tobacco. Under prohibition, these revenues accrue to traffickers as increased profits.

The right policy, therefore, is to legalize drugs while using regulation and taxation to dampen irresponsible behavior related to drug use, such as driving under the influence. This makes more sense than prohibition because it avoids creation of a black market. This approach also allows those who believe they benefit from drug use to do so, as long as they do not harm others.

Legalization is desirable for all drugs, not just marijuana. The health risks of marijuana are lower than those of many other drugs, but that is not the crucial issue. Much of the traffic from Mexico or Colombia is for cocaine, heroin and other drugs, while marijuana production is increasingly domestic. Legalizing only marijuana would therefore fail to achieve many benefits of broader legalization.

It is impossible to reconcile respect for individual liberty with drug prohibition. The U.S. has been at the forefront of this puritanical policy for almost a century, with disastrous consequences at home and abroad.

The U.S. repealed Prohibition of alcohol at the height of the Great Depression, in part because of increasing violence and in part because of diminishing tax revenues. Similar concerns apply today, and Attorney General Eric Holder’s recent announcement that the Drug Enforcement Administration will not raid medical marijuana distributors in California suggests an openness in the Obama administration to rethinking current practice.

Perhaps history will repeat itself, and the U.S. will abandon one of its most disastrous policy experiments

SO FAR this year, about 4000 people have died in Mexico’s drugs war – a horrifying toll. If only a good fairy could wave a magic wand and make all illegal drugs disappear, the world would be a better place.

Dream on. Recreational drug use is as old as humanity, and has not been stopped by the most draconian laws. Given that drugs are here to stay, how do we limit the harm they do? The evidence suggests most of the problems stem not from drugs themselves, but from the fact that they are illegal. The obvious answer, then, is to make them legal.

The argument most often deployed in support of the status quo is that keeping drugs illegal curbs drug use among the law-abiding majority, thereby reducing harm overall. But a closer look reveals that this really doesn’t stand up. In the UK, as in many countries, the real clampdown on drugs started in the late 1960s, yet government statistics show that the number of heroin or cocaine addicts seen by the health service has grown ever since – from around 1000 people per year then, to 100,000 today. It is a pattern that has been repeated the world over.

A second approach to the question is to look at whether fewer people use drugs in countries with stricter drug laws. In 2008, the World Health Organization looked at 17 countries and found no such correlation. The US, despite its punitive drug policies, has one of the highest levels of drug use in the world (PLoS Medicine, vol 5, p e141).

A third strand of evidence comes from what happens when a country softens its drug laws, as Portugal did in 2001. While dealing remains illegal in Portugal, personal use of all drugs has been decriminalised. The result? Drug use has stayed roughly constant, but ill health and deaths from drug taking have fallen. “Judged by virtually every metric, the Portuguese decriminalisation framework has been a resounding success,” states a recent report by the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank based in Washington DC.

By any measure, making drugs illegal fails to achieve one of its primary objectives. But it is the unintended consequences of prohibition that make the most compelling case against it. Prohibition fuels crime in many ways: without state aid, addicts may be forced to fund their habit through robbery, for instance, while youngsters can be drawn into the drugs trade as a way to earn money and status. In countries such as Colombia and Mexico, the profits from illegal drugs have spawned armed criminal organisations whose resources rival those of the state. Murder, kidnapping and corruption are rife.

Making drugs illegal also makes them more dangerous. The lack of access to clean needles for drug users who inject is a major factor in the spread of lethal viruses such as HIV and hepatitis C.

So what’s the alternative? There are several models for the legal provision of recreational drugs. They include prescription by doctors, consumption at licensed premises or even sale on a similar basis to alcohol and tobacco, with health warnings and age limits. If this prospect appals you, consider the fact that in the US today, many teenagers say they find it easier to buy cannabis than beer.

Taking any drug – including alcohol and nicotine – does have health risks, but a legal market would at least ensure that the substances people ingest or inject are available unadulterated and at known dosages. Much of the estimated $300 billion earned from illegal drugs worldwide, which now funds crime, corruption and environmental destruction, could support legitimate jobs. And instead of spending tens of billions enforcing prohibition, governments would gain income from taxes that could be spent on medical treatment for the small proportion of users who become addicted or whose health is otherwise harmed.

Unfortunately, the idea that banning drugs is the best way to protect vulnerable people – especially children – has acquired a strong emotional grip, one that politicians are happy to exploit. For many decades, laws and public policy have flown in the face of the evidence. Far from protecting us, this approach has made the world a much more dangerous place than it need be.

While Latin American countries decriminalise narcotics, Britain persists in prohibition that causes vast human suffering

There is no sign of reform emanating from the self-satisfied liberal democracies of west Europe or north America. Reform is not mentioned by Barack Obama, Gordon Brown, Nicolas Sarkozy or Angela Merkel. Their countries can sustain prohibition, just, by extravagant penal repression and by sweeping the consequences underground. Politicians will smirk and say, as they did in their youth, that they can “handle” drugs.

No such luxury is available to the political economies of Latin America. They have been wrecked by Washington’s demand that they stop exporting drugs to fuel America’s unregulated cocaine market. It is like trying to stop traffic jams by imposing an oil ban in the Gulf.

Push has finally come to shove. Last week the Argentine supreme court declared in a landmark ruling that it was “unconstitutional” to prosecute citizens for having drugs for their personal use. It asserted in ringing terms that “adults should be free to make lifestyle decisions without the intervention of the state”. This classic statement of civil liberty comes not from some liberal British home secretary or Tory ideologue. They would not dare. The doctrine is adumbrated by a regime only 25 years from dictatorship.

Nor is that all. The Mexican government has been brought to its knees by a drug-trafficking industry employing some 500,000 workers and policed by 5,600 killings a year, all to supply America’s gargantuan appetite and Mexico’s lesser one. Three years ago, Mexico concluded that prison for drug possession merely criminalised a large slice of its population. Drug users should be regarded as “patients, not criminals”.

Next to the plate step Brazil and Ecuador. Both are quietly proposing to follow suit, fearful only of offending America’s drug enforcement bureaucracy, now a dominant presence in every South American capital. Ecuador has pardoned 1,500 “mules” – women used by the gangs to transport cocaine over international borders. Britain, still in the dark ages, locks these pathetic women up in Holloway for years on end.

Brazil’s former president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, co-authored the recent Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy. He declares the emperor naked. “The tide is turning,” he says. “The war-on-drugs strategy has failed.” A Brazilian judge, Maria Lucia Karam, of the lobby group Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, tells the Guardian: “The only way to reduce violence in Mexico, Brazil or anywhere else is to legalise the production, supply and consumption of all drugs.”

America spends a reported $70bn a year on suppressing drug imports, and untold billions on prosecuting its own citizens for drugs offences. Yet the huge profits available to Latin American traffickers have financed a quarter-century of civil war in Colombia and devastating social disruption in Mexico, Peru and Bolivia. Similar profits are aiding the war in Afghanistan and killing British soldiers.

The underlying concept of the war on drugs, initiated by Richard Nixon in the 1970s, is that demand can be curbed by eliminating supply. It has been enunciated by every US president and every British prime minister. Tony Blair thought that by occupying Afghanistan he could rid the streets of Britain of heroin. He told Clare Short to do it. Gordon Brown believes it to this day.

This concept marries intellectual idiocy – that supply leads demand – with practical impossibility. But it is golden politics. For 30 years it has allowed western politicians to shift blame for not regulating drug abuse at home on to the shoulders of poor countries abroad. It is gloriously, crashingly immoral.

The Latin American breakthrough is directed at domestic drug users, but this is only half the battle. There is no rational justification for making consumption legal but not the supply of what is consumed. We do not cure nicotine addiction by banning the Zimbabwean tobacco crop.

The absurdity of this position was illustrated by this week’s “good news” that the 2009 Afghan poppy harvest had fallen back to its 2005 level. This was taken as a sign both that poppy eradication was “working” and that depriving Afghan peasants of their most lucrative cash crop somehow wins their hearts and minds and impoverishes the Taliban.

The Afghan poppy crop is largely a function of the price of poppies compared with that of wheat. The only time policy has disrupted this potent market was in 2001, when the old Taliban responded to American pressure by ruthlessly suppressing supply. Since the Nato occupation it has boomed, inevitably polluting Kabul politics and plunging western diplomats and commentators into hypocrisy over Hamid Karzai’s corrupt regime. What did they think would happen?

The crop has shrunk because the wheat price has risen and the recession has dampened European demand. It will rise again. The policy of Nato and the UN’s economically illiterate drug tsar, Antonio Maria Costa, of treating Afghan opium as the cause of heroin addiction, not a response to it, means trying to break supply routes and stamp out criminal gangs. It has failed, merely increasing heroin’s risk premium. As long as there is demand, there will be supply. Water does not flow uphill, however much global bureaucrats pay each other to pretend otherwise.

The trade in drugs is a direct result of their unregulated availability on the streets of Europe and America. Making supply illegal is worse than pointless. It oils a black market, drives trade underground, cross-subsidises other crime and leaves consumers at the mercy of poisons. It is the politics of stupid. The incarceration (pdf) of thousands of poor people (11,000 in England and Wales alone) also deprives economies of a large labour pool.

As the Brazilian judge pointed out, the tide of violence associated with any illegal trade will not abate by only licensing consumption. The mountain that must be climbed is licensing, regulating and taxing supply, thus ending a prohibition now outstripping in absurdity and damage America’s alcohol prohibition between the wars.

From the the deaths of British troops in Helmand to the narco-terrorism of Mexico and the mules cramming London’s jails, the war on drugs can be seen only as a total failure, a vast self-imposed cost on western society. It is the greatest sweeping-under-the-carpet of our age.

The desperate politicians of Latin America have at last found the courage to grasp the nettle. Will Britain? According to the UN, it has the highest number of problem drug users in Europe. I imagine Gordon Brown and David Cameron agree with the Argentine supreme court, but they are too frightened to say so, let alone promise reform. In all they do they are guided by fear.

I sometimes realise that, if Britain still had the death penalty, no current political leader would have the guts to abolish it.

One need not travel to China to find indigenous cultures lacking human rights or to Cuba for political prisoners. America leads the world in percentile behind bars, thanks to ongoing persecution of hippies, radicals, and non-whites under prosecution of the war on drugs. If we’re all about spreading liberty abroad, then why mix the message at home? Peace on the home front would enhance global credibility.

The drug czar’s Rx for prison fodder costs dearly, as life is flushed down expensive tubes. My shaman’s second opinion is that psychoactive plants are God’s gift. Behold, it’s all good. When Eve ate the apple, she knew a good apple, and an evil prohibition. Canadian Marc Emery is being extradited to prison for selling seeds that American farmers use to reduce U. S. demand for Mexican pot.

Only on the authority of a clause about interstate commerce does the CSA (Controlled Substances Act of 1970) reincarnate Al Capone, endanger homeland security, and throw good money after bad. Administration fiscal policy burns tax dollars to root out the number-one cash crop in the land, instead of taxing sales. Society rejected the plague of prohibition, but it mutated. Apparently, SWAT teams don’t need no stinking amendment.

Nixon passed the CSA on the false assurance that the Schafer Commission would later justify criminalizing his enemies. No amendments can assure due process under an anti-science law without due process itself. Psychology hailed the breakthrough potential of LSD, until the CSA shut down research, and pronounced that marijuana has no medical use, period. Drug juries exclude bleeding hearts.

The RFRA (Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993) allows Native American Church members to eat peyote, which functions like LSD. Americans shouldn’t need a specific church membership or an act of Congress to obtain their birthright freedom of religion. John Doe’s free exercise of religious liberty may include entheogen sacraments to mediate communion with his maker.

Freedom of speech presupposes freedom of thought. The Constitution doesn’t enumerate any governmental power to embargo diverse states of mind. How and when did government usurp this power to coerce conformity? The Mayflower sailed to escape coerced conformity. Legislators who would limit cognitive liberty lack jurisdiction.

Common-law must hold that adults are the legal owners of their own bodies. The Founding Fathers undersigned that the right to the pursuit of happiness is inalienable. Socrates said to know your self. Mortal lawmakers should not presume to thwart the intelligent design that molecular keys unlock spiritual doors. Persons who appreciate their own free choice of path in life should tolerate seekers’ self-exploration.

Bill C-15 in Canada. Presently in the Senate being 'debated'. Check it out. A huge step backwards to say the least.

Canada is in Afghanistan also.

Thanks Void Mirror for the info.

Valid medicinal value, it’s a victimless crime, the War on Drugs WAY too costly, too many arrests for simple possession, tax it and use the money to pay for health insurance and to reduce the deficit…Need I say more?

Woodstock Universe supports legalization of Marijuana.

Add vote in our poll about legalization at http://www.woodstockuniverse.com.

Current poll results…97% for legalization, 3% against.

Listen to RADIO WOODSTOCK 69 which features only music from the original Woodstock era (1967-1971) and RADIO WOODSTOCK with music from the original Woodstock era to today’s artists who reflect the spirit of Woodstock. Watch Woodstock TV.

Peace, love, music, one world,

RFWoodstock