Do you want to ‘Divide & Kreate’, ‘Kick Out The Clocks‘ or discover ‘K Time‘? These are the concepts Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty are promoting as part of their latest project, the K Foundation. In certain quarters, the adverts concocted by this organisation have been met with disbelief. Countless journalists seem convinced that Drummond and Cauty are simply throwing away the money they’ve earned from their pop hits on an expensive and pointless campaign. However, to anyone familiar with the history of the KLF and the various utopian currents that fuel the counter-culture, these ads make a great deal of sense.

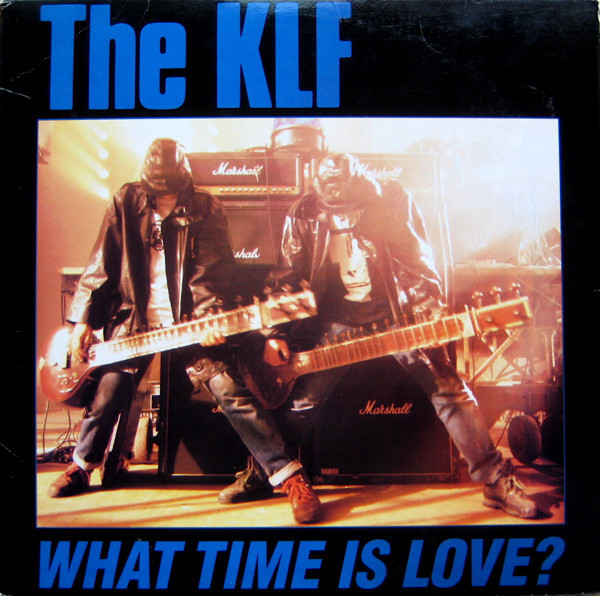

To understand the K Foundation, it’s necessary to acquire some historical knowledge. For those not in the know, Drummond and Cauty have been active in the music business for many years. Drummond moved from playing guitar with the Liverpool punk band Big In Japan, to setting up the independent Zoo Records, then on into management and A&R work for major labels. Among many other crimes against humanity, he is responsible for inflicting The Teardrop Explodes and Echo and the Bunnymen upon an unsuspecting public. Cauty is chiefly a musician. The first fruit of their collaboration was the single All You Need Is Love, released in March 1987. Drummond and Cauty promoted this attack on the media’s coverage of AIDS with a graffiti campaign in which the slogan Shag Shag Shag was daubed over advertising hoardings.

Having made a mark as avant-hip satirists, the JAMS or Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (as the duo dubbed themselves at the time), consolidated their cult following with the release of an album entitled 1987 – What The Fuck’s Going On? The platter received rave reviews in the music press, although the record was soon suppressed by lawyers acting for ABBA who objected to the heavy sampling of their hit single Dancing Queen. Drummond and Cauty milked the legal proceedings for press coverage, then released a new version of the LP with all samples removed and detailed instructions on how to recreate the original sound.

Further records followed under a bewildering variety of names, including Disco 2000 and the KLF. The duo had their first number 1 in 1988 with Doctorin’ The Tardis which was credited to The Timelords. It was at this point that Drummond and Cauty began earning the money that currently finances the K Foundation. Stunt was followed by stunt and these pranks acted as adverts for a series of hit records. In April 1992, Drummond and Cauty dumped a dead sheep on the steps of the hotel where the Brit Awards ceremony was being held and then went on to be named Best British Group. The following month, the KLF placed a full page advert on the back of the NME announcing that they would not be releasing any new material in the foreseeable future and that their entire back catalogue was deleted.

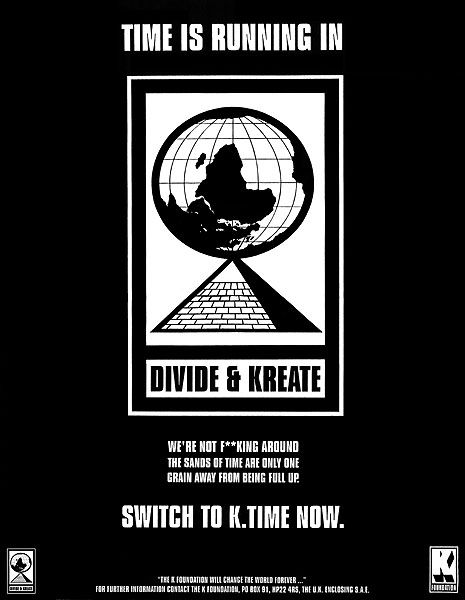

A year later, the existence of the K Foundation was revealed in the first of a series of one page press advertisements. Having established an identity for the K Foundation, the campaign went into higher gear with the advice that ‘TIME IS RUNNING IN… SWITCH TO K TIME NOW‘. Then came an advert for a record that wasn’t available. All three of these ads invited the public to send an SAE to a post office box for further information. To date, none of the people I know who wrote to this address have received a reply. Possibly the organisation has been swamped with requests for information because ads have appeared in the NME, Guardian, Independent On Sunday and Sunday Times.

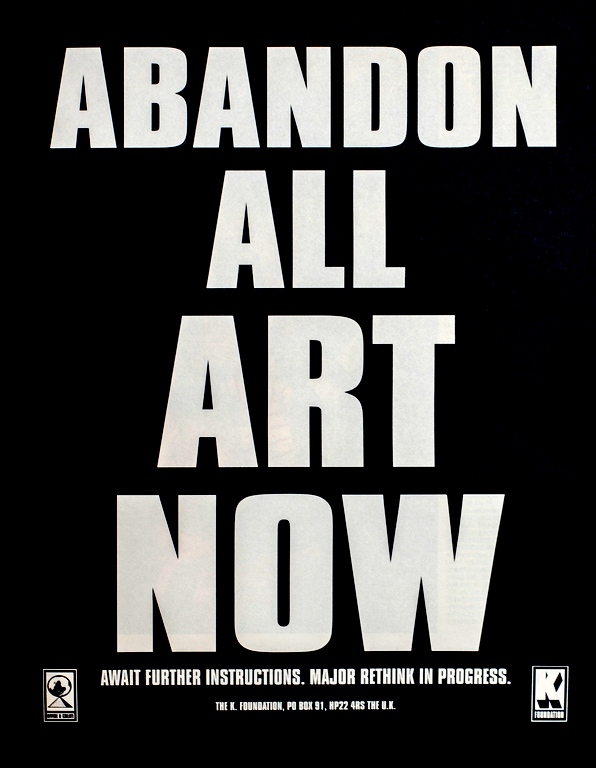

The campaign took a new turn with the fourth ad in the series, which consisted of the slogan ‘ABANDON ALL ART NOW‘ in letters nearly three inches high. After this came the announcement of the K Foundation Award, a forty thousand pound prize to be given to the artist who’d produced the worst body of work in the previous twelve months. The four nominees were identical to those chosen for the prestigious Turner Prize, which awards a mere twenty thousand pounds to its winner. The next ad in the campaign carried the headline ‘LET THE PEOPLE CHOOSE’ and a voting form, so that the public could have its say on who was the worst artist in the world.

Needless to say, Rachel Whiteread won both the Turner Prize and the K Foundation Award. Earlier in the year, Whiteread had obtained permission from Tower Hamlets council in East London to erect a temporary ‘sculpture’, in the form of a life-size concrete cast of a terraced house. It was the media coverage Whiteread’s supporters drummed up against the looming demolition of this eye-sore that brought her to widespread public attention. If, as is sometimes asserted by cultural reactionaries, the task of the artist is to give representation to the unconscious, Whiteread has succeeded admirably in her chosen vocation. Houses are traditionally considered a symbol of the unconscious, by filling a terraced house with concrete and then removing the brickwork shell, Whiteread showed herself to be intellectually, creatively and emotionally blocked — something that is evident in all her ‘work’.

In the promotional verbiage that surrounded this ‘work’, rather prosaically entitled ‘HOUSE’, Whiteread talked about the ‘sculpture’ being typical of the Victorian domestic architecture found all over London. Her desire to ‘universalise’ the meaning of this particular terrace, resulted in the original building being stripped of it’s history and the deep political implications of that history. One of the major sponsors of Whiteread’s activities was Tarmac, who were daily throwing people out of their homes so that big business could bulldoze unwanted motorways through Britain. Whiteread had nothing to say about the politics of housing until it was suggested that the money wasted on her ‘sculpture’ could have been better spent building homes, at which point she shamelessly began claiming that ‘HOUSE’ was somehow a protest against homelessness!

In the Times on 23rd November 1993, Richard Cork was given half a page to berate ‘Britain’s perennially begrudging attitude to the avant-garde’ on Turner Prize day. Among other things, Cork defended Rachel Whiteread’s reactionary work HOUSE as ‘an austere yet melancholy monument’. Neither Whiteread nor Picasso, who Cork also ‘defends’ in his piece, are actually members of the avant-garde. As Peter Burger points out in his book THEORY OF THE AVANT-GARDE, avant-gardism entails a critique of the institution of art — whereas Whiteread and Picasso enjoy an unproblematic relationship with the art world.

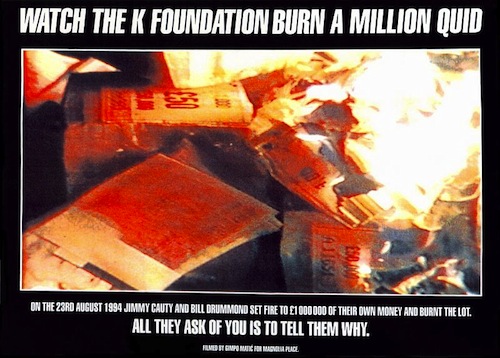

After Drummond and Cauty announced they’d burn forty thousand pounds worth of low denomination bank notes if Whiteread refused to accept them as prize money, this ‘artist’ took the K Foundation’s cash ‘under protest’, claiming she was forced to do so to avoid the dosh being wasted. Whiteread either has a very low estimation of the public’s intelligence or else she is just plain thick. Money is only a symbolic representation of wealth; burning it doesn’t alter the sum total of resources in the world. Indeed, millions of bank notes are burnt every year because they have become worn through use. Drummond spent a good part of Turner Prize day talking to Whiteread on the ‘phone and he concluded from these conversations that ‘she isn’t very bright’.

Drummond and Cauty dealt explicitly with the symbolic nature of money in a series of ‘works’ they created to compliment the K Foundation Award. The Melody Maker of 4th November 1993 reported that they’d produced a series of ‘art works’ which consisted of money nailed to pieces of wood, and that these were to be sold for half the value of the cash they contained. The following press statement was also quoted: ‘Over the years the face value will be eroded by inflation. While the artistic value (due to the works’ position in the amended History of Art) will rise and rise. The precise point at which the artistic value will overtake the face value is unknown. De-construct the work now and you double your money. Hang it on a wall and watch the face value erode, the market value fluctuate, and the artistic value soar. The choice is yours.’

In November 1993, the avant-garde wasn’t to be seen at the Turner Prize gathering, it was to be found among that select band of individuals who’d organised the K Foundation’s attack on the smug complacency of the arts establishment. Thanks to the adverts Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty placed around the WITHOUT WALLS tv coverage of the Turner Prize ceremony, ‘dignitaries’ such as Lord Polumbo were revealed as buffoons. While Polumbo ranted about the dunces who attack cultural innovations, his rhetoric showed him to be a complete idiot — several people immediately pointed out that he was unable to correctly name Van Goth’s art dealer brother. Likewise, Polumbo claimed that there are no monuments erected to critics and presented himself as a champion of progressive culture, while ignoring the fact that it was critics who picked the winner of the prize he was awarding.

It is the K Foundation, rather than Whiteread, who represent a vital and innovative strand within contemporary culture. Their work is simultaneously a critique and a celebration of ‘consumer capitalism’. Above all, what’s enjoyable is the gusto with which they attack the self-righteous bureaucrats who pretend to be the guardians of our culture. From the beginning, what struck me about their campaign was the way in which it drew on the same underground and avant-garde sources that had inspired many of the KLF’s finest moments. While Drummond and Cauty have moved away from the pop industry, there is a deep sense of continuity between their earlier music based work and the recent multi-media campaign.

One of the few influences on the KLF that music journalists have been able to pin down is that of Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea’s Illuminatus novels. The historical material on which these books are based is part of a millenarial current that runs through western culture from the very beginning of the Christian era to the present day. These tendencies are given a more secular veneer in both communist and fascist doctrines. On the left, they are expressed in terms of ‘the end of history’. The Nazi obsession with establishing ‘a thousand year Reich’, is a different formulation of very similar concerns. Likewise, the K Foundation’s infatuation with time and its transformation is rooted in the same soil, although the branch to which Drummond and Cauty belong is that of mystical anarchism.

Springing from the same source, but to date not fully recognised as an influence on the KLF and K Foundation, is the twentieth-century tradition of avant-gardism. Movements such as the Futurists, Dadaists, Surrealists and Situationists are well known for the pranks they pulled on the cultural establishment. F. T. Marinetti paid for his First Futurist Manifesto to appear as an advertisement in Le Figaro of 20 February 1909. In this text, Marinetti spoke of his desire to ‘destroy the museums, libraries and academies of every kind’. In other words, like the K Foundation campaign, Marinetti’s Futurist advert was an attack on institutionalised art.

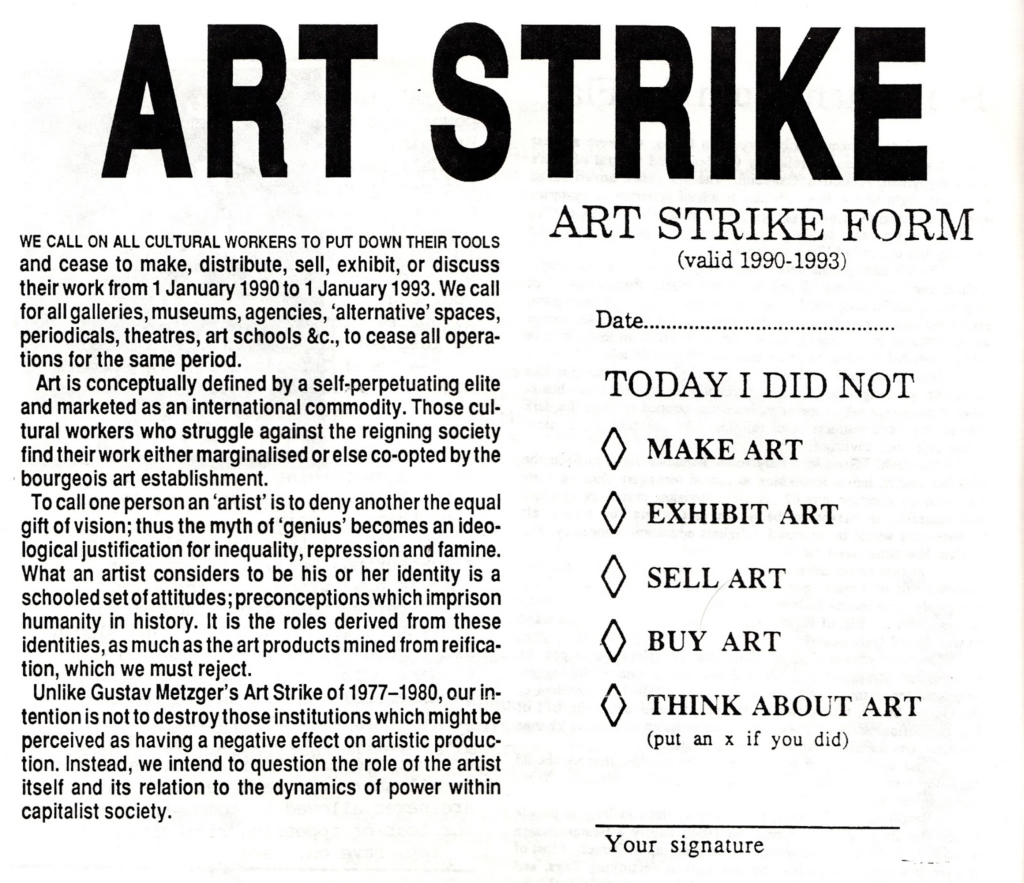

Drummond and Cauty have been described on numerous occasions as Situationists, but to label them as such is rather misleading. Situationism is simply one of many movements that make up the twentieth-century avant-garde tradition. The K Foundation are undoubtedly an outgrowth of this tradition but their work is not explicitly Situationist. Indeed, it has much more in common with the Neoist, Plagiarist and Art Strike movements of the nineteen-eighties than with the avant-garde of the fifties and sixties.

Obviously, the KLF (Kopyright Liberation Front) shared an interest in plagiarism with the eighties avant-garde. Over the past decade, columnists in avant-garde magazines such as Photo Static and Vital have spent a great deal of time ranting about why xerox machines and sampling technology make all existing copyright laws redundant. Likewise, during the eighties, a series of Festivals of Plagiarism were held in Europe and North America so that those concerned with these issues could meet and promote their cause. Drummond and Cauty drew on the heated discussion taking place everywhere from unofficial galleries to small circulation magazines and transformed it into something capable of setting the pop charts alight.

Another concern of the eighties avant-garde was with the use of multiple names as a means of raising questions about the nature of identity. By 1986, fifty different avant-garde magazine editors were calling their publications Smile, which of course caused a great deal of confusion. Even more people were using the name Karen Eliot — so that countless pictures, articles and songs, were produced by an artist who didn’t actually exist! In a similar fashion, Drummond and Cauty’s use of a variety of names for their musical projects made the listener question traditional notions of authorship.

From 1985 onwards, propaganda began circulating amongst the avant-garde for an Art Strike, during which cultural workers would stop producing and selling any product. Drummond and Cauty’s 1992 decision not to release any more records echoes these demands and provides another example of how they’ve taken ideas developed on ‘the margins’ of contemporary culture and used them to great effect within the pop ‘mainstream’.

Returning to the K Foundation adverts, we can see that they make perfect sense when viewed in the light of the avant-garde tradition that runs from Futurism at the beginning of this century through to groups such as the Neoists and the London Psychogeographical Association in the eighties and nineties. The ultimate meaning of the K Foundation’s slogan ‘ABANDON ALL ART NOW’ is remarkably similar to that of ‘DEMOLISH SERIOUS CULTURE’, a formulation much used by the Art Strikers. As I’ve already said, the avant-garde has always been concerned with criticising institutionalised art.

As one would expect, much of the press reacted with utter incomprehension to the K Foundation’s brilliantly conceived campaign. Charles Nevin, writing in the Independent On Sunday, described the advertisements as ‘screamingly obscure’. Susannah Herbert and Victoria Combe, reporting for the Daily Telegraph, spoke of the K Foundation being ‘incapable of reckoning the year correctly‘. Robert Sandall, in the Sunday Times, suggested that the campaign ‘served no obvious purpose other than to fritter away about £70,000’.

Several articles have stressed the fact that Drummond and Cauty have no recorded product available. This is not actually true, since much of the KLF output is readily available as American, German and Japanese imports. Likewise, the supposedly suppressed 1987 LP can be obtained easily enough in its original form as a bootleg. However, even if there was actually no product available at the retail end of the trade, the ads could still generate income for Drummond and Cauty because publishing remains the most lucrative area of the music business for major acts. Apart from anything else, the K Foundation campaign has exposed the pundits who’ve suggested the ads are economically unviable as being completely ignorant of how the entertainment industry operates and what constitutes effective advertising.

Meanwhile, a Guardian article by-lined to John Ezard, called the K Foundation Award a ‘hoax’. This description is utterly misconceived. From a financial perspective, the K Foundation Award is considerably more substantial than the Turner Prize. Rather than questioning the validity of Drummond and Cauty’s activities, anyone with a modicum of intelligence will see the intervention as a means of deflating the value of prizes awarded by bureaucratic institutions for what a bunch of suits imagine to be individual creative excellence! The K Foundation campaign functions on numerous levels but the so called quality press appears incapable of comprehending this.

And so, Drummond and Cauty are succeeding in another of their stated aims, which is to ‘divide and kreate’. The pundits who found the K Foundation campaign ‘confusing’ clearly belong among the ranks of reactionaries. Those who see the campaign as a remarkable manifestation of the contemporary avant-garde, will no doubt join the growing band of individuals who wish to build a new culture, so that they can live in a world of ever-growing ecstasy. As for future K Foundation plans, Drummond and Cauty are keeping them under wraps. When I ran into Drummond a couple of months ago, he simply told me, ‘I do what I have to do’. Something will come up and we’ll know soon enough that the K Foundation are involved in fanning the flames of creative liberation.

_____________________________

An amalgamation of an article for G-Spot and material from a lecture at Trinity College, Cambridge, this mix of the material was first published in Rapid Eye #3. edited by Simon Dwyer (Creation Press, London 1995).