A former Metropolitan Indian (member of a situationist-influenced group in Italy) recounts some experiences with the group during the “Years of Lead”: the violent late-1970s.

It all began a long time ago but our story leaps the intervening periods and begins in fact in the spring of 1975. It had been a bloody spring. Fascists and police had killed militants belonging to the left. Practically overnight the situation was radicalised. In this moment of political and ideological stasis, the political and ideological struggles in the late 1960s and early 1970s were reaping their predictable rewards.

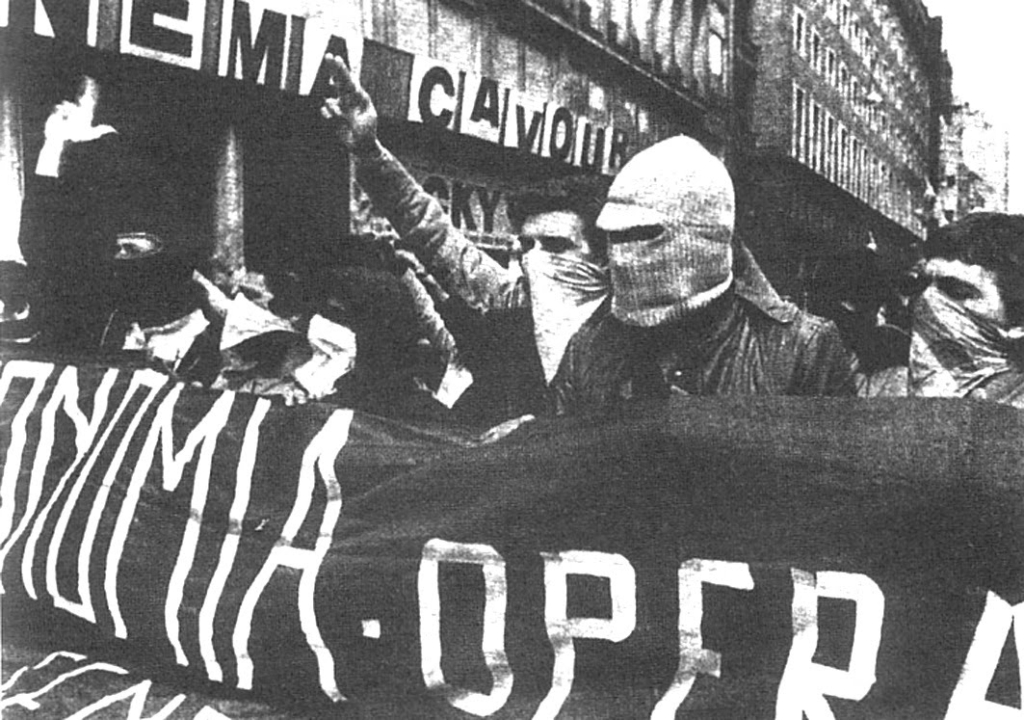

However, an event occurred (one amongst many) which, passing almost unnoticed, was to quickly reveal its importance as a sign of the times. Some 100 militants from Lotta Continua broke away to set-up autonomous groups, collectives and similar bodies of the same order. Their implication was none too clear to the youthful masses who had wearily dragged themselves along to agitate in the seedy little groups of the extra parliamentary left. But by the end of the year they had a more precise connotation. In fact the creation of the first groups of Workers Autonomy (Autonomia Operaia) dates from around 1972, the same year in which Rosso was founded in Milan and the Via Volsci collectives in Rome.

In June 1975, the first Italian regional elections took place. The PCI (Italian Communist Party) scored a striking victory with a 7% increase in their vote. It was not yet the party of the majority in Italy as the DC (Christian Democrats) still maintained a few points lead, but it had conquered a relative majority in all the big cities, even in Naples the centre of clientilism and corruption.

On the evening of June 6th 1975 in the Bottega Oscura (CP headquarters in Rome) the left were exultant – even the most extreme of the extremists. Crushed in a crowd, which was laughing and crying for, deep down (yet so deep down) they were thinking they had not agitated in vain, that all those deaths had served some purpose and that Italy was “red”. It was the triumph of the “historic compromise”, of Berlinguer’s (CP General Secretary) social democracy initiated scarcely three year previously at the end of a period of intense struggle for the proletariat.

The summer slipped by between more or less alternative music festivals. In these crowded festivals the enthusiasm of youth looking for new experiences had not yet been extinguished.

Drugs, including heroin, which had made its appearance the previous year on the Italian market for mass consumer goods, were spreading, forming part – in spite of the hostility of political formations – of the quest for new experiences. Autumn 1975 was marked by another episode, carelessly brushed aside at the time but which was a classic forewarning, signalling a situation which was becoming ever more insupportable to young proletarians.

The occasion was provided by a large anti-Franco demonstration. In Madrid 5 militants belonging to FRAP (armed Maoist group) and ETA (armed Basque party) had been executed. The newspapers, which today would call them terrorists, then described them as patriots. Two demonstrations had been called, one by the parties proper and the other by the smaller parties (Lotta Continua Avanguardia Operaia, Partito del Unita Proletaria). This second demonstration had terminated in the Piazza del Popolo in the centre of Rome. That evening while meetings and torch light processions were taking place, a few hundred people shouting, “burn down the embassy” suddenly shot off down the Via del Corso, the most elegant street in Rome, and began looting shops. On the following day it was estimated 37 shops had been looted. The suppression of this action had not come from the police, rather it came from stewards belonging to the various groups ready, once more to loyally demonstrate their bureaucratic purpose and do the dirty work normally left to the police.

At all events the silent haemorrhaging of the small parties continued and many militants went on to form autonomous collectives in thought and in action, separate from all logic of a party political character.

In December 1975 there took place the first and perhaps only national gathering of all these autonomous groups. It was organised by the Via Volsci collective, which was to the forefront of collectives with a quite strong presence in the work place. Unfortunately we have not been able to find any documents originating from within the assembly itself and as a result we are not in a position to provide even partial account.

In retrospect, we can see however that it was these groups, which came to constitute the array of ideas and action that defined “Workers Autonomy” (Autonomia Operaia). It was unified at a theoretical level by an ideology which, even if in practise was not homogenous, did have in common a clear cut refusal of reformism as practised by the PCI and the groups alike. This refusal was to be expressed in a certain cult, though not exclusively, of street violence and rebellism:

1. Autonomous factory and neighbourhood collectives spread the length and breadth of Italy.

2. Autonomous assemblies in the big factories in northern Italy.

3. Autonomia Operaia (Workers Autonomy) collectives (hospitals, ENEL Electricity Board)). Some had come from particular groups (like the CUB related to Autonomia Operaia) who stressing the necessities of their own work situation had, thanks to that, often scored a notable success as a result of the radicalism of their methods of struggle.

4. The “Rosso” group. This was a movement (as it now defined itself) newspaper. Many were cadres and ex-militants from Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power). It is necessary to go into this separately because these militants were the only link in 1977 with the movement of 1968/’69 and the beginning of the 1970s.

5. Those who had left Lotta Continua in Rome and southern Italy for various reasons.

6. The ‘creators’ – to use capitalist terminology – libertarians, ex-Potere Operaio (Workers’ power), anarchists. The most well known were those from Bologna who along with Radio Alice and the review A/traverso were immediately to become the main point of reference for the movement in the first half of 1977.

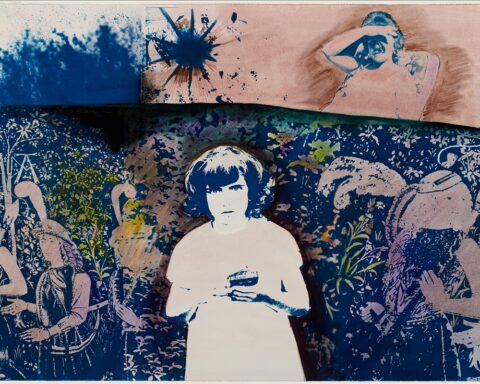

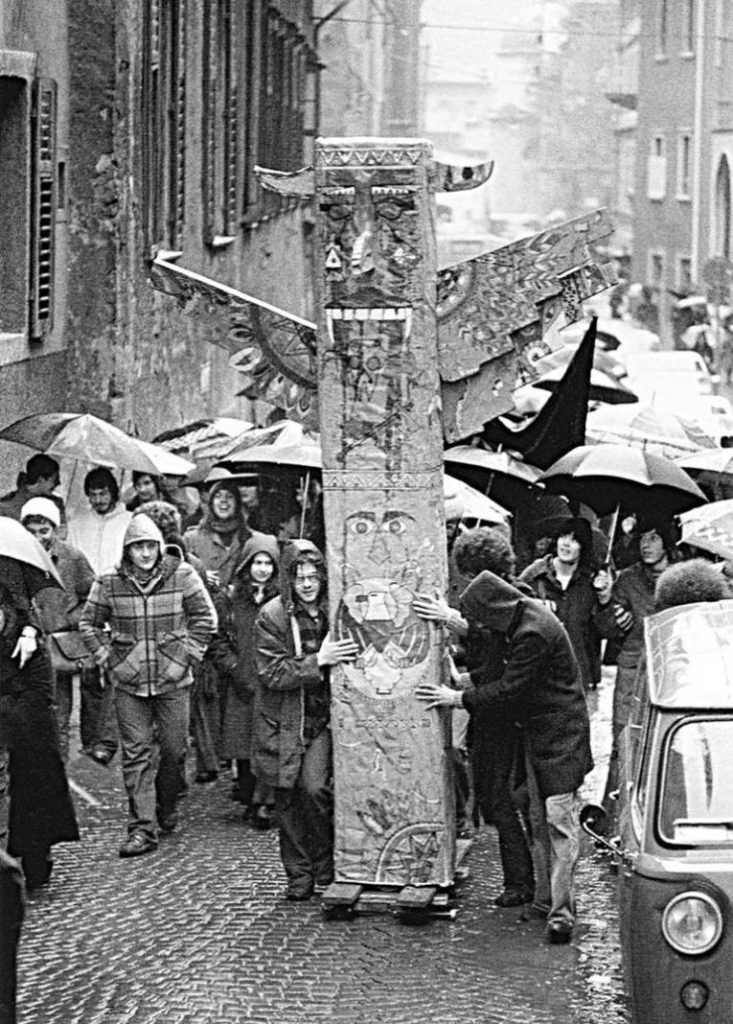

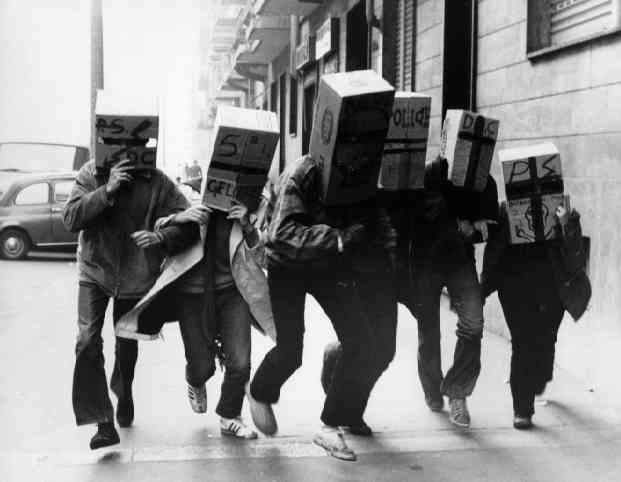

In fact it was within the ambit of the latter, there took place in December 1975 another event which had little immediate consequence but whose fertile influence in Italy was enormous. This was the emergence of the first public sortie of the “Metropolitan Indians” or (more precisely) “Geronimo” the ex-Cassio collective. The genesis of this group shall serve to elucidate partially the formation of so many groups coming from the urban periphery.

The background of the people belonging to this group was very different coming from Lotta Continua, Autonomia Operaia, the PCI, Via Volsci, etc. Moreover, the group included many isolated proletarians, nowhere people from the back of beyond.

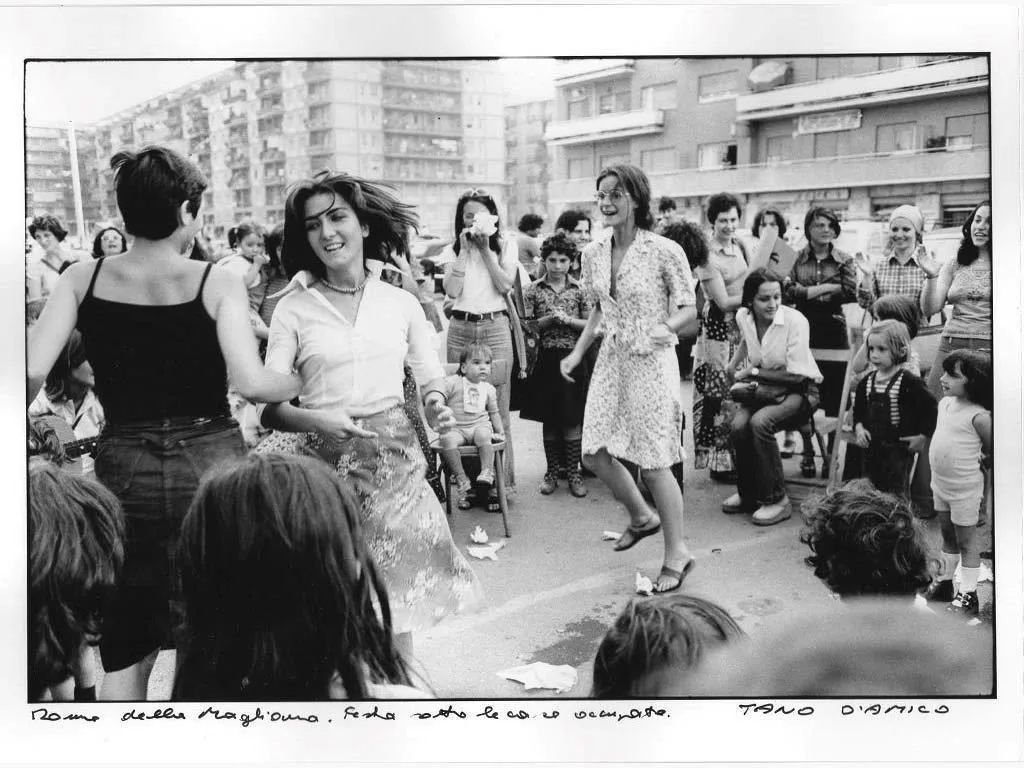

Events, neighbourhood games, the occupation of parks, partially gutted houses as well as attacks on bulldozers belonging to building contractors, were organised. Strongly opposed to local sections of the PCI “Geronimo” became very active in neighbourhoods.

The idea of defining themselves Metropolitan Indians came about almost by chance. One evening during which the group had organised a sortie to cover neighbourhood walls with graffiti like “death to the sense of guilt”, “masturbate peacefully” etc it became necessary to find a name for the group. At one point someone shouted, “Let’s leave the reservation” (meaning by this the ghettoes of the big cities, i.e. metropolitan ghettoes). The rest came of itself. Geronimo was the American warrior who dared leave the reservation without asking permission.

On Xmas Eve 1975 Geronimo organised a series of provocations against the local church. It was a question of pushing an action to a paroxysm: this was even to be its essence, a parody of lived experience. Whilst some poured pots of red paint on the steps of the church others wrote on the surrounding walls: “bourgeois bastards, this is the blood that Christ sheds everyday in the streets and in the factories” – it was a semi-bourgeois, semi-proletarian neighbourhood.

Geronimo survived for a further five months during which it organised in addition to going to Autonomia (autonomy) demos’, its own “acid” Committees, self-criticism groups and parties.

As a matter of fact everyone enjoyed themselves a lot and felt free finally to step off the beaten track. Spontaneity and parody merged with a criticism of everyday life. To introduce a theoretical note, certain members of the group attempted to put together a small magazine with a situationist content. But the result was a total break with the editors of this magazine who found themselves excluded.

But the explicit demands of Geronimo very rapidly found a fertile ground on which to expand. It was February 1976 and the occasion was provided by a demonstration in aid of comrades who had been arrested. On it were Lotta Continua, Autonomia Operaia, Pdup, Au Communista etc and Autonomia Romagna, which at this time was a group few in number comprising essentially the Volsci collective. Geronimo comprising some 50 people assembled behind the Volsci, carrying a multi-coloured banner. The Volsci, workerists to the core, were ill at ease with the mix. However, to begin with, it was only a verbal conflict. Then later when the Volsci broke away from the procession formed from individual groups, to seek a confrontation outside the Regina Coeli prison, Geronimo followed them resolutely. The confrontation with the police did not take place. On the contrary, in the little procession the slanging match had reached a critical point. From being verbal, the confrontation became physical. Certain of getting the upper hand, the former attacked with sticks but Geronimo promptly charged the attackers really letting them have it. In the wrangle the inevitable happened, a large number of comrades who had trouped behind the Volsci banner switched over to Geronimo who numbered behind its banner something like 300 people when the procession ended. It was another revelatory sign of how strong the individual need to be liberated from oppressive rnilitantism was. It was a great success for Geronimo. It had asserted itself as an autonomous group, which it was, without compromise and without demanding anything of anyone.

With all the comrades in Rome knowing about Geronimo it ceased to be only a neighbourhood phenomena from that day. An article in La Republica newspaper came to the conclusion it was the most radical group and in fact ended by saying “one cannot exclude links with NAP”. This was completely ridiculous as it was precisely the target of Geronimo’s attacks.

Anyhow, a link was forged with people in Rome who looked towards Radio Alice in Bologna. After the group was dissolved (which was not decreed by some jumped up nobody, simply that it had nothing more to say) the movement continued unabated.

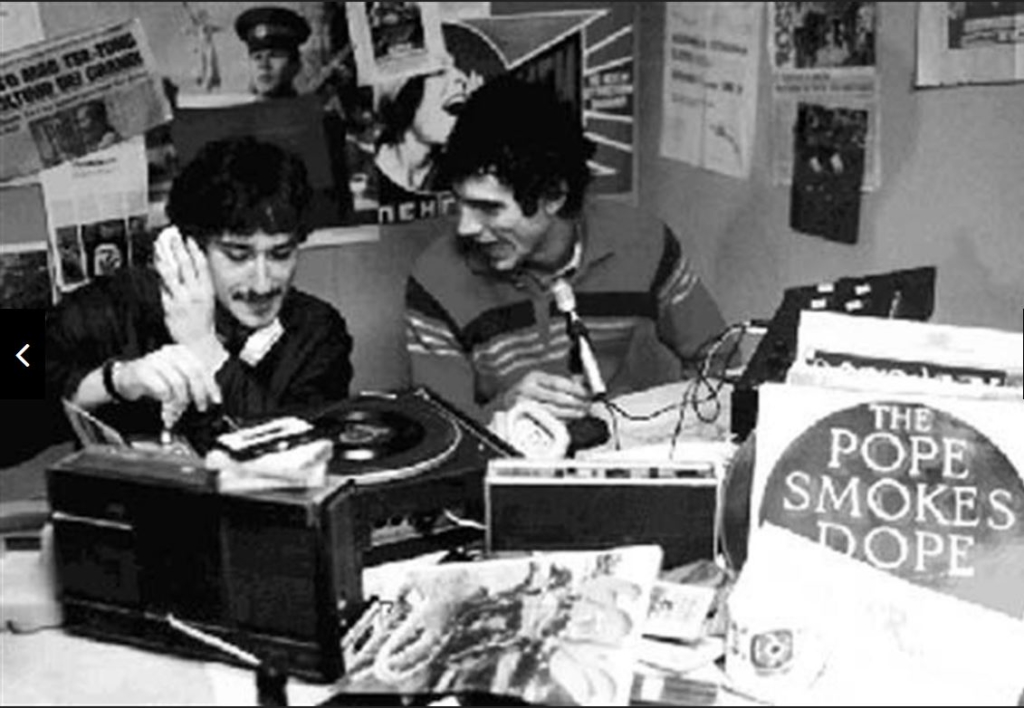

Links, which had been forged during the demonstration in February, gave birth in May of the same year to a kind of plenary assembly calling for the creation in Rome of a radio station for the movement in contact with Radio Alice. Although there was no shortage of ideas, money was scarce and for this reason a sizable group got into contact with an already existing Radio Bleue. For a definite period of 3 to 4 months Radio Bleue (whose interests lay in fact entirely in the opposite direction) was transformed into a radio station belonging to the movement, alternating with the groupuscule radio Citta Futura or, if you like Fottutta meaning an anarcho.

It was June 1976. Lotta Continua at the Rimini Congress had agreed to dissolve. It was plain to see no one there had anything more to say and that henceforth voting for the PCI was a good idea plus counselling people to comply with the great party of the working class.

In the legislative elections in June, the PCI confirmed its advance remaining however behind the DC. lnspite of that, with 34%/35% of the vote it found itself decisively placed when it came to forming a government. Anticipating the entrance of the PCI into the Government the unions gathered together in a plenary assembly at the sports palace in Rome and decided to initiate a social contract. This decision for those who still had any doubts on that score, confirmed the institutionalised character of our unions. This development merits a further explanation but let’s return to the movement and look at what was happening to it in Rome.

During the summer Radio Bleue had invented a new way of conceiving radio and politics making use of parodies on news broadcasts, information on the autonomous movement, anti-statist sketches and a music that was in opposition to the constraints imposed by multinational recording companies. But the core of the disagreement with the owners’ concerned themost directly politicised broadcasts in which the autonomous collectives spoke freely. By September the wrangle had become impossible. There were attempts later at broadcasts on Radio Citta Futura but the radio’s directors Renzo Rossellini and Sandro Silvestri (now a director of a multinational firm) did not permit any coverage of the movement.

Autonomy continued to advance. The poxy political manoeuvres of the unions began to bear fruit. Unemployment was rising remorselessly. The young were really being kicked from pillow to post.

In Milan auto-reductions were organised at cinemas. Every Sunday a large number of people under the watchful eye of group stewards would make their way to a posh cinema, paying a reduced price for tickets. Until the opening night of La Scala this was more or less successful. With the aim of attacking the bourgeoisie done up in their best on their way to La Scala, the circles of proletarian youth from Milan and autonomous neighbourhood groups, were to stage guerrilla events in the centre of Milan. The result was one great cock-up. Crushed by the total disorganisation, thanks to the behaviour of some organised autonomy sections, many young comrades were hurt in the confrontation. The papers exaggerated the affair and autonomous groups had their moment of notoriety.

Auto-reductions were also organised in Rome on two consecutive Sundays. This bore no relation to what was taking place in Milan because in Rome the groupuscu1es did not possess stewards. Thus everything concerning the groups was in comp1ete disarray. The result was spontaneous confrontations.

On the first occasion on December 1st a thousand or so people had gathered in the drizzle in the Piazza Cavour. The aim was to get into the Adriano Cinema. A contingent of police was all that was needed and on being charged the crowd scattered.

The following Sunday things were different. During the week without any stickers or leaflets the rumour spread especially in the schools. Come Sunday 5000 comrades had gathered in the Piazza Trilussa in Trastevere. The “America” cinema was attacked from the outset. Some sort to purchase an auto-reduced ticket but immediately realizing it was not about that; the crowd entered the cinema with no intention of watching the film. The police charged and arrested – an ironical stroke – the people attempting to buy auto-reduced tickets. The mass of the people left the cinema and formed a procession, which marched towards Testaccio, a popular neighbourhood in the city centre.

At the “Victoria” cinema people burst inside without delay this time. Not everyone succeeded in getting in and the police charged and dispersed the crowd outside. Inside there remained some 200 people under siege. When night fell an agreement was reached after several attempts to charge the cinema. Without a blow being struck the surviving remainder withdrew from Testaccio.

They were the first symptoms of a malaise which was to become widespread amongst the youth whether students, workers or marginals. The New Year passed and 1977 arrived. No one, not even remotely guessed what was to happen. In the first weeks of January tension was high but nothing occurred.

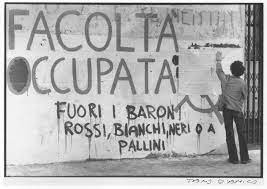

On January 23rd the Humanities Dept was occupied to protest against the reforms proposed by the Christian Democrat, Malfatti. The papers barely reported the news. It seemed a theatrical occupation organised solely by militants. After staying away three days many began to take a look for themselves. The first debates commenced and attempts were made to bring people together but all these initiatives still appeared unrelated and gave no one any satisfaction.

It was merely the beginning. In a matter of days a blazing fury burst out in many individual and collective acts containing in a single moment both prologue and epilogue, consummating the desires of those taking part.

The first act unfolded on February 1st: a fascist attack took place in the Law Dept. Comrades who were occupying the Humanities Dept went to the aid of those in the Law Dept. The fascists fired wounding two comrades, one seriously in the head. On the same day a revolt began which straightaway went beyond the immediate situation, given that the fascists were only one aspect of state repression. After the Humanities Dept, students occupied the Physics Dept, the Teachers Training Dept and the Engineering Dept. On the same evening Italian TV began colour transmissions.

The following morning the battle began and firearms made their appearance in the street.

We will never know who fired first and it scarcely matters to us.

A demonstration was called against the fascists and there were assemblies in all the schools. During the demonstration some fascists were punched then shots were heard – hand gun and machine gun fire. An officer belonging to the public security arm of the police fell to the ground, shot in the head and two comrades from the Autonomy collective, Paulo Tomasini and Daddo Fortuna were seriously injured in the legs by a machine gun wielded by public security agents. They were arrested and charged with attempted murder having been found in possession of a gun. The story grew and the news spread all around Rome. Come midday and the university was packed with people. Sharp exchanges and insults flew directed at militants from different groups and their loyal followers who supported the notion of a student occupation by students.

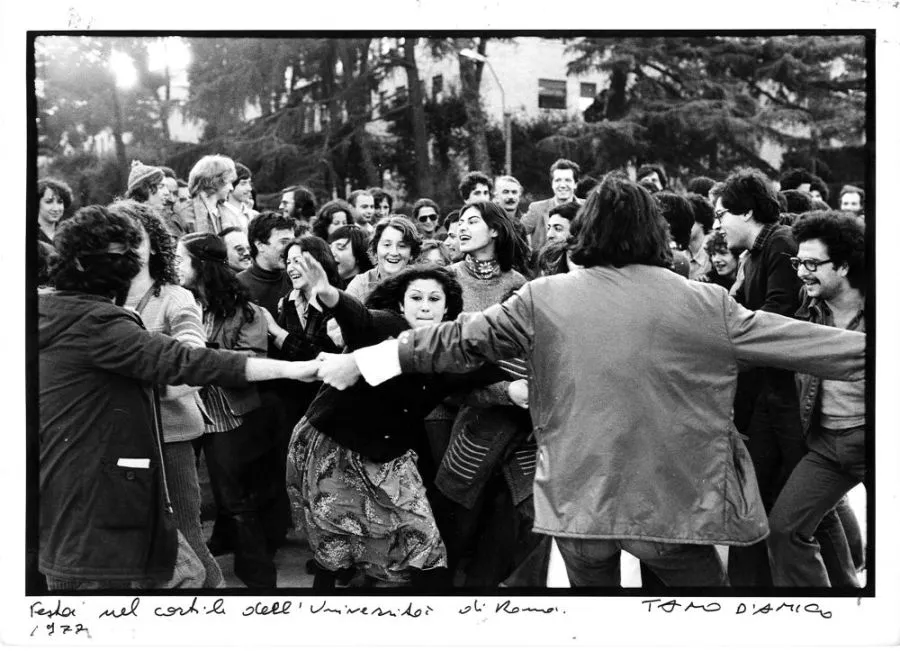

People thronged to the university from every neighbourhood – school students, the unemployed, youth from estates on the urban periphery, druggies, gays, young workers in the black economy. This was the ‘movement’, which exploded. It had scarcely seen daylight before it began to bawl out loudly and ever yet more loudly causing, even if it was only for a few moments, the pillars of the social contract to shake – i.e. the unions and the party – even if it was far from achieving its real objectives, the institutions of capitalism.

These were the great days during which marginals, autonomists from neighbourhood collectives and work places, footloose mavericks of every variety united in hot pursuit of pettifogging political parties, wresting from them any attempt to reduce the movement to a series of organs, reflecting in miniature, the institutions themselves.

“La Rivoluzione” (a Mao-Dadaist paper from Bologna) wrote:

“On demonstrations we cry out: “it’s another 1968”. “No it isn’t ’68” Rinascita replies. We say it is another ’68 in intention, to underline the desire to turn everything upside down as then and to engage in a process of struggle, which will be broad and powerful, not just a flash in the pan, something off the cuff. At the same time however we are living through a different process. It is much more massive than before, far more radical far more determinedly anti-reformist. Because it is composed of proletarians, of people who are already working, have worked already, or are looking for work. It is not reducible to a student dimension. Today, explosion is the continuation of a history begun in April 1975, which has grown throughout ’76 eventually broadening out into a movement of young proletarians. The February movement was the conquest of a mass social terrain and the central territory of the university by a subject incarnating the refusal of work.

It is the moment of creating free space.”

“La Rivoluzione” wrote (Number 12, March 1977):

“The solution consists in the growth of the movement itself. Marginals coming together at several different points on the urban terrain, occupation of space and houses, meeting places and Departments. Inspection committees, for instance made up of workers and the unemployed to enforce the new conditions of life, wages and work, providing work for the unemployed and regularsing casual employment.

To arrive at a generalised rupture let’s make a leap. The terrain remains the same but the programme becomes:

Liberation of inner city areas, (workers quarters, marginal quarters, university precincts). Here we will impose a “political price” on the enemy who will be forbidden to enter (cops, carabinieri, fascists and PCI).

Generalised expropriation of Church property and property belonging to it. Generalised occupation of empty houses. In the liberated areas the numbers at work are to be increased, overtime is to be banned, work undertaken whose terms the movement will determine.

All this is indispensable and a possible mode of organising a counter-power. Without thought, this might be translated into institutional terms or be taken by the state.

Rome University, the cultural fortress, became for 15 days a liberated space (even if this was illusory because there remained within the university precinct, a police station, although a pretty inactive one, which had been set up after ’68) with the intention of realising what autonomous circles had announced some while ago.

During the first few days of February rage and desire exploded in this space in a violent fashion. On the one hand it was ephemeral and illusory but also quite real to all the proletarians present. All false pretexts were swept aside (the Malfatti reform, anti-fascism etc.)

Thus, a total hammering out began, the subversion of daily life pushed to the point of paroxysm with the desire to be liberated from all constraints. And those who affirmed themselves to be the social subject were all those proletarians who right from the days immediately following the struggles of ’68/69 had become known to sociologists, politicos, psychologists and professionals of the party of revolution, bent on preaching to the masses, a pure object of academic discussion. In schools and universities they had extolled proletarianisation and passing through the school of the working class.

All these dregs, the miserable residues of Stalinism and the epigones of reformism, found themselves isolated, derided and ridiculed in every conceivable way. The movement of the “none guaranteed” as it had defined itself put an ever-greater distance between itself and militantism, which it aspired to leave behind forever.

“Fantasy shall destroy power and laughter will bury it” appeared on the walls of the university.

Whilst the PCI began, through its press, a terror campaign against the movement, to show to its friends in the Government its determination to go the whole hog in its role as policeman of the proletariat, the occupation of university departments continued apace.

In early February the PCI and the groups tried to set up some tin-pot assemblies to bring everyone back within the fold of institutionalised “ordered” and “peaceful” protest against the Malfatti reform. In fact, no one knew any longer what it referred to. So much so, that “Paese Sera” (PCI paper) referring to the “youth occupying the university” wrote on February 8th “they don’t even know what they are struggling for any longer”.

On February 5th, the Prefect of Police banned the demonstration fixed for the following Saturday. The occupation of the university up till then limited to the Humanities Dept became total.

In the “liberated” precinct, debates, games, amusements, the fantasia of proletarian festivity continued without let up. The atmosphere that reigned was of a liberated neighbourhood (a wall was separating it from the rest of the world) emulating the Paris Commune. At a more elitist level, the Chicago Commune and Paul Mattick were dusted off by “Marxiana”, the only theoretical journal that enjoyed some credit then.

But the movement’s creativity was expressed in a myriad other ways. What occupied the most privileged place during this period, beyond the struggle against the institutions, was the ludic dimension. Henceforth, this was the impulse behind the decisive victory over the union cops who tried to put a stop to the horror of the February 17th occupation.

Commencing from this date, the movement abandoned the illusory terrain of street confrontation to explode in the re-appropriation of entertainment. Each assembly was supported by theatrical events staged by groups of people ridiculing the daily pontificating of “politicians”, inventing slogans, which changed by the minute. In the space of a day was born the CDNA. (Centre For the Broadcasting of Arbitrary News) the Nazichecka, the Craxi group (“Long live Comrade Bettini Craxi scourge of the fascists who gets around in a taxi” – Craxi was of course Prime Minister – TN).

The more homogenous groups who forsometime past had already fought against the PCI’s social democratic project and who in the main had gathered around Radio Bleue brought out “La Rivoluzione” together with Radio Alice. In the meantime, Radio Alice had been creating a movement of far greater consequence than in Rome (all things considered). “La Rivoluzione”, was a national paper and by way of introduction published the following manifesto:

“WORK MAKES YOU FREE AND BEAUTIFUL”

In the current economic situation millions and millions of young people risk, during a long period not being able to enjoy a fundamental right/duty which is, however, guaranteed by the constitution, to all citizens whose only goods are their chains: namely wage labour.

It is thus that the incentive to get up before daylight, one of the most lively and salutary traditions of our way of life, is being lost to whole generations. Next to go, the regularity and good humour, which characterises the existence of the honest labourer, gives way to confusion, anxiety and deviation. As psychologists, criminologists and sexologists’ stress, isn’t work an excellent remedy against drugs, pederasty and bestiality?

For workers who already have a job, on the contrary, new and unexpected perspectives open up for them and for the development of their work capacity: henceforth, notably thanks to overtime, the creativity and exuberance of adult workers will be able to grow and achieve limits which no one would have dared envisage before now.

But it is not right to be carried away with enthusiasm before such results: While the healthy plant of employed workers grows and prospers, the dry shrub of a lazy and marginal youth becomes more sterile every day.

This is why trade unions and democratic forces, together with the association for parents of runaway children, propose the following jobs for young unemployed:

1. Efface graffiti on walls, schools, factories, universities and toilets.

2. Increase religious and monastic vocations, as well as police vocations.

3. Reforest the bald mountains of the islands and the Apennines.

4. Restore all volumes hanging around libraries page by page, following the instructions of Giorgio Amendola (TN: CP big wig).

5. Cement-up all dens of subversion and chaos.

6. Constitute edifying groups for young marginals.

7. Distribute to students who are behind in their studies a demi-hectare of virgin land in Irpinia, Aspromonte or in the Modonia.

8. Rediscover in a definitive way the last vestiges and remains of World War One.

9. Establish re-education centres for the treatment of worker absenteeism.

10. Self-sacrifice is not enough.

11. Self-immolation is the only way.

This manifesto, like many others, although written before hand, came out only after February 17th, the day Lama (General Secretary of CGIL the CP led union federation) was chased out. Unfortunately I don’t have any tracts and photocopied leaflets from this period.

On February 17th exactly the movement faced its first space/time crises when repression began to shift the movement onto a terrain somewhat different to street confrontations toward a banding together and self-absorption. But during February that was not felt to be an immediate danger.

The movement evolved practically entirely in the direction of self-awareness and in the inevitable nature of its existence and essence. Thus it affirmed the refusal of wage labour and as a result, all forms of workers’ organisation, which ended up in trade unions. This notion was taken to its extreme, to the point where wage labour was considered anti-revolutionary in that it did not partake of the immediate refusal of its own condition. However, not only did it delineate a formal rupture with the traditional communist movement but one that questioned the substance itself of the individual choice of each proletarian. The end result was an exaltation of casual work, non-guaranteed labour and the sub-proletariat as the immediately revolutionary subject in opposition to waged workers whose job was guaranteed by the unions. All this was expressed through festivity and parody. It was really due to these internal practises that the movement drastically rejected all attempts at spectacularisation and stardom (that no leader emerged was not down to chance). It went as far as the assembly decreeing after a public trial of journalists from the PCI, “Corriere della Sera” and “La Repubblica” that no journalists were to be allowed to enter the university. The position taken against the spectacularisation of the media, the PCI and its policing role and the bourgeois press which “sought to understand” was unambiguous.

On February 9th 30,000 people demonstrated in Rome. It was a peaceful demonstration, which passed practically unnoticed, journalists appearing to be more interested in what was transpiring in the occupied university.

At the same time the unions launched a strike in schools and universities against the “Malfatti Reform” (which was undeniably reactionary but it was not a question of going into the details but a matter rather of a pretext for anyone concerned). The PCI and the unions carrying out by proxy the behest of the high and mighty circulated through their papers an invitation to a dialogue with the “sane” (not exactly accurately identified) part of the movement. The grande finale to this music hall turn would be, according to the aims of the organizers, the meeting with Lama in the occupied university. It was announced beforehand as though it was an invitation from “the workers” to a dialogue. It was trumpeted forth as “Lama goes to talk with the university occupants”, power being only too glad to leave it to the PCI (who, for its part, continued to want to demonstrate its zeal was unimpeachable) the thankless task of lancing the boil.

February 17th was quite warm for the time of year. The sun seemed about to come out anytime but from time to time a fine drizzle would delay its appearance. The quadrangle of the Minerva, the centre of the university campus slowly began to fill. Militants belonging to the PCI and the union put up a makeshift platform and a loud speaker system adjacent to the Law Dept, formerly a fascist stronghold and now used by the PCI and certain other groups for their earbashing ceremonies. At the other side of the quadrangle comrades regrouped around the Humanities Dept, the movement’s centre.

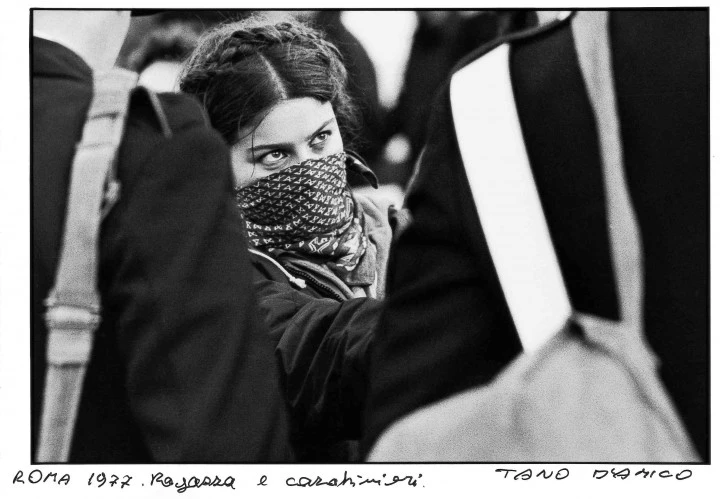

In the front were to be seen the “heads” which the bourgeois press had attempted to, more than once, recuperate in the form of spectacle. Dressed in multi-coloured clothes, their faces covered in grease paint they wore an expression somewhat between anger and laughter. With them are the non-organised comrades, the uncontrollables (literally “unchained dogs” TN). The more organised comrades from the remaining autonomous collectives stayed to one side – at least to begin with. Before the Humanities Dept were grouped hardly more than 3000 to 4000 comrades. In comparison to the 7000 to 8000 militants the PCI had brought in as an occupying force, the comrades belonging to the movement were in a minority.

To begin with they just stared each other out. Then, on the platform, Lama opened his mouth to speak and immediately he was barracked. A chorus of “imbecile, imbecile” continued uninterruptedly in the background, punctuated by cries of “Lamas are in Tibet” and “the PCI and the unions are provocateurs. Shaking with fear they are at the service of the state”.

The PCI heavies lost their cool and threw themselves into the fray. A furious onslaught was unleashed against those who on this occasion were the state’s policemen. With stones and fire extinguishers at the ready the movement had, minutes later, turfed-out the provocateurs, destroying the platform and all the symbols of mystification. With a single voice the shout was raised “this is our space and you will not succeed in taking it from us so easily”.

The herd of militants legged it as fast as they could. The girls were in tears. Many amongst them had begun to reflect, some were to change and join the movement. Whilst the crowd massed in the forecourt of the Science building chanting their defiance, comrades took up positions at the locked gates. Meanwhile the PCI’s hit squad went in search of isolated comrades who coming from the schools and adjacent quarters continued to flock towards the university. Many were roughed up.

It had been a great victory and everyone was happy and content. But the victory was as sweet as it was short lived. Whilst the PCI was ordering its troops to withdraw, the police once more surrounded the university. They came super-equipped with their new fireproofed armoured cars and bullet-proof vests. And this time they came in earnest.

It was lunchtime and in the university there were only some 2000 to 2500 comrades. People who risked entering to lend a hand to those now under siege inside, were roughly searched by the police. An assembly was called and after a brief discussion an impossible resistance was rapidly organised. All the gates were barricaded except one to allow for escape.

The attempt to erect a barricade the entire length of the main entrance was a bit of a shambles in seeking to block a space of some 30 metres with cars, flower pots, benches etc. The sun went in – it had shone during the hour of victory over the invader. Everyone, both inside and outside the university, knew they would be evicted sooner or later but the resistance that was mounted was not purely formal. It was a concrete way of saying “goodbye”. It was the conviction of being part of a growing movement, a movement that was made up of subjects, not objects. It was a conviction which, although real within terms of the movement was revealed to be illusory in relation to the rest of society. It was to lead to an overestimation of the events, which followed.

Towards evening the police went into action. The armoured car charged the flimsy barricades across the main entrance. Just behind came Martian aliens advancing clumsily in their space suits and on first seeing them one wondered if they had laser guns!

The spectacle ended with the university in flames. It was a military occupation taking away from the movement its arena. This was not just a formality and the consequences of this break up were felt rapidly. For the time being people transferred to the Economics Dept outside the university campus.

The university was closed.

Following February 17th the assemblies which were held throughout the entire city in schools, neighbourhoods and some work places were to heighten every time the level of confrontation. The alternative henceforth was clear: either with us or against us. For the PCI and the state, the question had been settled right from the start. However, it was after February 17th that a rift developed in the plan to suppress the movement. The PCI, who had been given the task, had failed: even worse, after the confrontation some trade union cadres timidly began to sympathise with the movement. In some districts and work places this phenomenon was particularly important.

The hour had at last arrived when the state had to take on the task of repression completely. Seeing that “political” recuperation wasn’t possible, the only alternative was to destroy the movement by dragging it onto the terrain of the spectacularisation of violence. This meant its concrete aspects were not given an emphasis any longer, only, to the exclusion of all else, its formal aspects. Obviously the “plot” which Judge Catalonsalti had mentioned, referred to the one organised by the state to destroy and isolate the movement.

The media spieled out its own version creating the following personages:

1. The hippy like Indian “heads”: ripe for recuperation.

2. The intellectual always ripe for recuperation.

3. The autonomist brandishing a P.38 pistol: non-recuperable, bad, to be eliminated.

One must point out that the movement was more deeply rooted than the institutions had been led to believe and it would provide a lot more to chew on before it would permit itself to be dressed in stage costume.

In the days that followed people continued to meet in other places like the Economics Dept and student residences. The amount of graffiti appearing on walls increased, as did the ironical sending up of institutions. On February 23rd a large, peaceful demo playfully wound its way around Rome. The Indians daubed S. Carvieri in green paint.

The number of universities that henceforth were occupied were many. Apart from Rome and Bologna there were Florence and Perugia and then Naples, Bari, Sassari, Cagliari and Palermo.

The movement’s fulcrum was in central Italy, backed up by southern Italy. It was in these places that the weight of unemployment was most keenly felt and where the concept of class was far less determined by the capitalist nexus. The refusal of work was interpreted along the lines of there was no work and it seemed impossible for there to be any. There was the endemic refusal by the state to import from the north a productive capitalist structure, dismissing the social benefits to be had from drawing people into wage labour. Two tendencies were present in this refusal of work. On the one hand there was a progressive desire to overcome a poverty stricken human condition. And, on the other there was a specific feeling, typical of a pre-industrial society which boiled down to demanding a system of state support (the case of the Neopolitan proletariat).

A signal was awaited from Milan and the industrial triangle i.e. from those sectors of the proletariat most directly involved in the productive process. But the movement in Milan brought to its knees by years of groupusculism produced nothing more than militantism and sectarianism. Even the young proletarian circles had been engulfed by these sectarian games. It was not by chance that some of the people who had produced “Insurrezione”, calling also for a spreading of the movement across the entire territory moved immediately to Rome. In Milan, throughout the whole of 1977 there came nothing other than a discourse of death – an increasingly extreme confrontation of representation cut-off from the productive reality of the north.

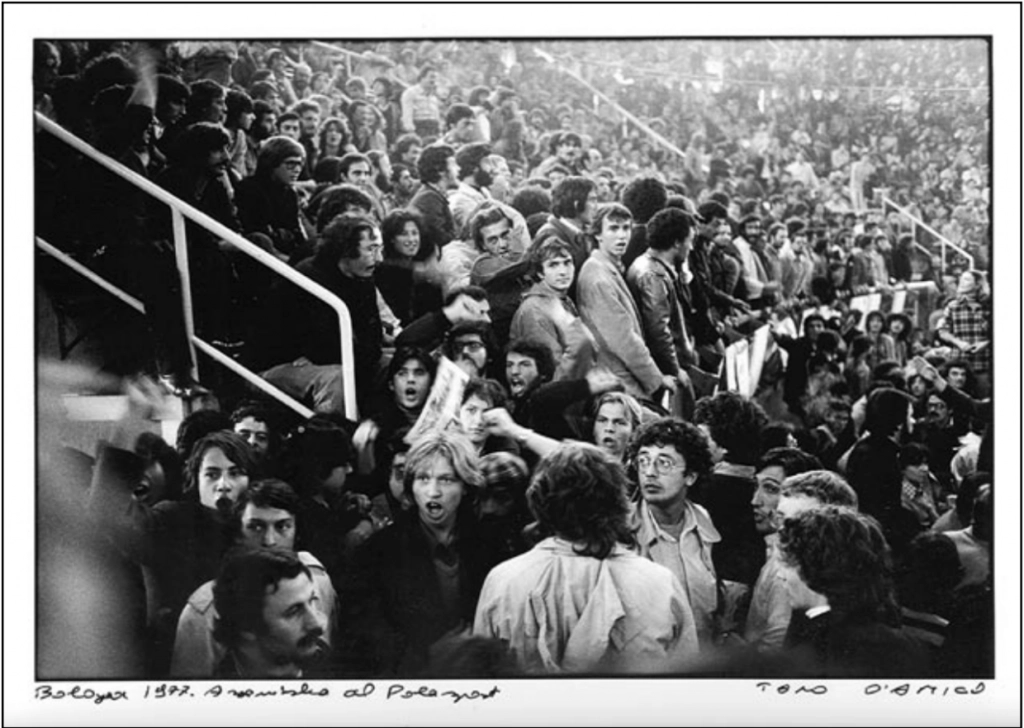

At the end of February, on the 26th and 27th to be precise, the first national assembly was held in Rome in the Economics Dept. The attack on the reformist and militaristic tendency flared into the open once more. It was a violent attack – giving rise to misunderstanding and confusion.

The following is from “La Rivoluzione” (No.11): “The Rome Assembly”:

“Minoritarism is defeated, prepare for revolution immediately. Rome, February 26/27th 15,OOO revolutionaries, expressions of situations where the movement is already on the offensive, from the movement of the unemployed in Naples to the displaced persons of Bari, to the Metropolitan Indians, to the Mao-Dadaists in Bologna, to the workers’ coordinations in Milan …..

It is crystal clear to those whose vision isn’t clouded that in the assembly groups don’t confront and oppose one another. Rather, in their respective positions, a socially based mass movement is evident, capable of bringing about, with the overthrow of capitalist power, a successful programme of total transformation.

It is crystal clear reformism and the party of small business are out of the running. Their presence already constitutes a provocation and the Berlinguists’ (Berlinguer was then leader of the PCI – (TN) denounced and scattered have been driven out because it is necessary to put a wounded animal out of its misery.

It is crystal clear that Adup and Autonomia Operaia are revolting lice, a mite unsure whether to take up residence on the back of social democracy or the movement.

It is crystal clear that destroying lice is an elementary hygienic precaution.

It is crystal clear lice and fascists have come to Rome to cause trouble but everywhere they came up against the kind of response a mass movement of the proletariat manifests.

Within the movement no coercion is necessary. Whoever has not grasped this, who holds problems can be resolved with the aid of shock troops and through the display of macho force, has remained bogged down in the most wretched minoritarism. Making a great deal of fuss, it is a leftover on the verge of extinction. The behaviour of sectors of Autonomia Operaia (Workers Autonomy) – the organised part with a capital A – comporting themselves on military style parades, acting in a violent, aggressive way with comrades, young people and women observes the logic of coalitions. It indicates a profound inability to grasp the newness contained in the movement. But the worst thing is by now imposing a minoritist and organisational logic, whether of a militarist or workers stamp, they risk forcing on the movement a centrist position alien to it.

Inspite of the militarist pressure exerted by these sectors the Rome assembly came out victorious and unitary. The Metropolitan Indians rejected manipulation by the wretched palefaces of the Pdup (jacket, tie, cashmere sweater), the motion was carried by thousands of cries of approval, and the concluding feeling was one of decision, convinced the movement would not falter.

The restoration of the paranoiac stage of politics with all its aggressive armoury, voluntarism and repression threatens to crush and deny reality, that which exists, the revolt born from the transformation of everyday life and the break with the mechanisms of constraint.

But what is obscene floats to the surface once more and the corpses of the institutions and the paranoiacs of militantism carry away the phrasemongers”.

The motion adopted by the assembly was in reality a bit weak, because at that point, the bulk of the forces present had been wasted by internal battles. The motion claimed all the street confrontations that had taken place up to then (including the ones in the Piazza Independencia) as part and parcel of the movement and proposed “mobilizing for a direct link-up with factories, quarters and schools in order to re-launch the struggle for full employment, a reduction in the working week, a wage increase and to oppose restructuration. It was decided to send a mass delegation (in practise anyone who wanted to go) to the FLM (Federazione Lavoratori Metal Mecanica) meeting, which was to be held in Florence the following week.

Really it boiled down to things many had taken for granted already. They had hoped the assembly would provide a point of departure in determining on a revolutionary strategy however minimal. The necessity of re-affirming it put the accent on the degree of disinformation and the vanity of enclosing each space and political group within a predetermined trajectory.

What did emerge was a general lack of preparation tending to favour isolated concrete acts undertaken often as an end in themselves and as the only practicable revolutionary terrain.

Preparations were laid for the days of revolt. Over and above the discussions the movement simmered, feeling an ever stronger need to re-appropriate public space to encounter the city. But repression restricted it to a generalised anger. Revolt was imminent. Everyone needed to stick together to reoccupy the university campus to be in a position to say more. But events supervened narrowing the space for creation and reflection.

On February 28th two pupils from the “Mamiani” school were wounded one seriously, by a fascist who was not properly identified. In the light of events that followed, in particular the most important, the fascist could also have been a state agent – however to ascertain if this was the case was henceforth impossible.

The “Mamiani” school was one of the schools where the movement was at its strongest. It was a bourgeois school, the most bourgeois in Rome. Inspite of the fact the FGGl (young communists) had, at least by the end of the year, some 100 members and activists out of a total of 2000 pupils, the movement had taken root there, creating a situation of permanent agitation, as in many other school, which no one could stand aside from. Playful forms of self-management and assemblies were organised which made it impossible for the functionaries of the little scholastic parliaments to continue with any kind of activity. Teachers who glorified in ’68 were openly challenged being, in fact, the most ferocious champions of social democratic normalisation.

There spread throughout Rome’s schools a capillary movement, which was total and in same respects infantile but which assuredly desired to challenge and attack “left” culture as recuperated by the spectacle of the party game.

The “Mamiani” school was a focal point within this framework being a school for the children of the enlightened bourgeoisie – a school for tomorrow’s leaders of recuperation (the same state of affairs as today in fact).

The demonstrations in response to the attack were however monopolised by the anti-fascists of the PCI and the groups.

Come the end of February, there was no getting away from the fact, the movement of opposition in the schools was a broadly based phenomena. The schools that were occupied and self-managed numbered more than 20, which is over half the high schools in Rome.

On March 1st the Humanities Dept was re-opened. But on March 4th a further repressive provocation struck the movement. Fabrizio Panzieri, a comrade belonging to the movement accused of killing a fascist during a street battle two years earlier, was condemned to nine years in prison. Thus the judicial practise of “moral responsibility” was commenced which today has been amply exploited by our repressive judicial apparatus.

There had been trouble in the court on that same evening. The demo of school students called for the following morning passed without incident. But by the afternoon many people had gathered in the university. But the police refused to allow the demonstration to leave the university perimeter because it had been banned. In the university whilst some were debating what to do, very violent confrontations broke out in the San Lorenzo quarter adjacent to the university, which then started to spread toward the centre. This time guns were repeatedly used, shots ringing out from every direction – it was no longer a question of an isolated incident. Some police cars were hit and a small car set alight. Two carabinieri suffered gunshot wounds. In the centre of Rome from the Largo Argentina to the Trastivere trouble erupted. Practically everywhere attacks took place – on a bank, a police station in the Piazza Farnese, the Ministry of Justice and in the Via Avenula. Lastly, a gun shop was attacked, the same one that had been looted a week earlier. Barricades made from burning cars were impossible to count.

On the following day the rector ordered the university to be closed remaining garrisoned by the police.

It was March 7th and in Florence the national conference of the FLM (the engineering union), which the movement had been invited to take part, was held. But throughout the two days of the conference the situation of incommunicability between the movement and the workers became accentuated. It reached the point where the movement questioned the idea of a union even – not just its controlling function – a thing which was in fact central to the workers’ delegates who subsequently held an assembly in the Lirico in Milan disclaiming the official position reached by the tri-partite union meeting. It was not a matter of weakness or incapacity but sprang from the fact that the demands put forward by the movement as immediately realisable were regarded by the employed working class as utopian and unrealisable. Translated into practise, the refusal of work became unemployment rendering survival impossible as a consequence. In the class more directly involved in the productive process there was not, in short, that apocalyptic sense of the end of time which pervaded the movement, becoming the dominant spirit in the days immediately after.

A national demonstration was fixed for March 12th in Rome.

But on March 11th a revolt broke out in Bologna. The bourgeois newspapers straightaway stated that this revolt, which lasted for two days, had involved thousands upon thousands of comrades, townsfolk and proletarians. It had been provoked by some 50 autonomists who had not been properly identified but who refused to allow a meeting of the Comunione e Liberazione (a Christian Democrat youth organisation) to go ahead in the university.

However, there was no getting away from the fact that an extremely determined struggle had been waged by the Bolognese proletariat. The Comunione e Liberazione holed up in the university by the comrades asked the rector, Rizzoli, for help. It was he who brought in the police and carabinieri. The movement immediately organised a protest demonstration. According to those taking part in this little demo a small detachment of carabinieri began firing blindly at the comrades who instantly fled. But someone amongst them did not. He was Pier Francesco Lorusso, killed by a bullet in the back. Lorenzo Tramontini was the carabiniero responsible.

It was the spark that set Bologna alight. Radio Alice immediately informed the comrades about what had happened. A demonstration wasn’t even called. The anger of the Bolognese proletariat, though poorly supported and hemmed in, exploded into furious revolt.

The university quarter of Bologna, right at the heart of the historical centre became for two days a liberated zone from where attacks were launched against all the symbols of bourgeois peace and quiet and local social democratic power – shops, banks, gun shops, the station – nothing was exempt from the anger of the proletariat.

It was a genuine, authentic revolt even if it never remotely took on the features of a revolutionary situation because it was the expression of a minority of the proletariat, no matter their number and determination. In any case, it really shook the institutions, particularly the PCI because Bologna was the jewel in the crown of its social democratic project. So much so that in order to safeguard it, armoured vehicles were sent in at 6 am on the morning of March 13th to remove the barricades. Throughout that entire day battles kept breaking out only to spend themselves before the military detachments, which were to be a permanent fixture in Bologna until the September Congress. Radio Alice which had sought constantly to supply counter-information and to rally people was closed down by a police raid and the editors arrested or obliged to go on the run like all the most active elements in the movement in Bologna.

On the morning of March 12th many people had arrived in Rome from all over Italy.

On the morning of March 12th many people – too many people! – had arrived in Rome from all over Italy. The national demonstration of school students set for March 11th had been transformed into a national demonstration against state repression and murder – like that of Lo Russo’s. By early afternoon an enormous crowd of comrades had gathered in the Piazza Esedra. The predominant feeling in the hearts of the 100,000 people gathered there had an apocalyptical touch to it – the ultimate expression of rage and anger. This was reinforced by the city’s appearance like as if it was under siege: shops were closed, no pedestrians about only detachments of police and carabinieri in riot gear.

The clearest political judgement passed on this day was given on the same evening by all those comrades who weren’t merely seeking in the movement a spectacular flare up, but an action oriented continually toward the creation of a genuinely revolutionary situation which they consciously felt to be a long way off.

Such a large concentration in Rome emptied all the other Italian cities of the vanguard of struggle (where the conditions existed that could foment rebellion) and created the situation of a pitched battle against the armed force of the institutions, which even though tired out after journeying through the night was well equipped and trained. In fact the entire effort was concentrated on Rome, which militarily was unfavourable because it had been occupied in a particularly highly trained manner. Thus the chance was lost to extend the struggle to the entire peninsula where demonstrations on a much smaller scale took place instead.

If one had to make a show of force Rome was probably the right place to do it in, in so far as it is the institutional centre of a well-organised powerful movement. However, it remains true that tackling the institutions through all out confrontation on a military terrain was a tactic doomed to defeat. It was not a matter of storming a Winter Palace, henceforth stripped bare, but of organizing a capillary action to circumvent all attempts at normalisation. And, further, to bring into the movement all those proletarian strata, which were still having doubts about the social democratic programme.

To storm the Montecitorio or the Palazzo Chiga was a mad idea not only because from a military point of view it was impossible to pull off but also, because even if it were to come about, we would be right back to square one. The need, in other words, was to work out really revolutionary ideas. The absence of any communication with the working class was a problem that was deeply felt by the movement and, after the March days, in an even more acute form.

“La Rivoluzione” dated March 19th, 1977 wrote: “The Movement and Power”

“Faced with the bosses attack on living and working conditions and on organisation there is no other way.

Bourgeois power is aiming at one thing – to get workers on their knees, cut wages, stamp on the indexing of wages and increase exploitation savagely.

If it succeeds in destroying the student movement and the unemployed movement, it will succeed in destroying insurrection. After that it will be the turn of factory workers. It is therefore necessary to engage in struggle immediately and to collate all the information coming from the barricades that tens of thousands of young students and the unemployed alongside advanced workers have erected in Bologna, Milan and Rome.

To prevent the movement from being massacred there is no other way except to carry the fight into proletarian quarters.

To block the path of Cossiga’s fascism, the armed violence of special units and counter revolutionary terror, there is no other way but to carry the fight into proletarian quarters.

Let us work out a programme on which to construct power: the force is not lacking to impose an increase in the workforce, plant by plant, quarter by quarter; the force is there to reduce overtime and speed-ups. The force is there to occupy the 100s’ of 1000s’ of empty houses while 100s’ of 1000s’ of proletarians don’t have a place to live. The force is there. Comrade workers, there is no other way. Comrade workers for hell’s sake let’s unite in struggle”.

With the benefit of hindsight we could say the force would have been there if the comrade workers had come along. And on March 12th in Rome instead of force the movement expressed its emotion, spontaneously deciding to openly confront. It was not therefore a pre-ordained decision but it did reflect badly on the capacity of groups of comrades who had analysed the situation more clearly. Over the preceding days they had created a broadly based revolutionary consciousness going beyond a rebellism of street confrontation which would only incline the movement towards a mad destructive militarism as had already been observed in the national assembly held in February.

So 100,000 people had assembled in the Piazza Esedra in Rome. Trembling with rage they were packed against the railings of the metro yard facing the police drawn up several lines deep in the Via Nazionale. Rome the beautiful was deserted, the sky was overcast, the shops closed and in the streets there was not a soul to be seen. It seemed the street had been cleared so the battle could take place without doing too much damage.

Towards 5 o’clock the demonstration moved off. Even the Indians with their painted faces, displayed under their cheerful make-up, signs of anger. Even they, like over half the other demonstrators, carried under their coats molotovs, bricks, stones and some had guns.

The demonstration moved forward slowly, unpunctuated by slogans no one in the Via Cavour would hear. It began to rain. The stewards, to coordinate action attempted to pass around an instruction to block the historic centre, in order to repeat on a larger scale what had already happened in Bologna (where the effectiveness of the police was greatly reduced because they were from Rome).

The front of the demonstration crossed the Piazza Venezia and arrived at the Piazza Argentina. The Corso Vittoria had been blocked off by a detachment of very well equipped carabinieri. Then, at that moment, whilst the front of the demonstration tried to pass word back about the barrier to those behind, the attack broke out in a predictable, disconnected manner. One, perhaps two, projectiles were thrown at the police guarding the headquarters of the Christian Democrats in the Piazza del Gesu. In a split second all hell was let loose. The long procession splintered into several fragments. Some sought to save comrades who weren’t organised for a street battle, letting them cross the river to reach a quieter spot .At the same time, others confronting the armed deployment of police and carabinieri created a wall of fire.

To describe the guerrilla events that took place that day, which the press described as “Black Saturday” may appear superfluous. But it is useful for measuring the range of confrontation which in spite of the insanity shall always remain a moment not easily forgotten.

After the attack in Piazza del Gesu, a few dozen comrades tossed molotovs through the Ministry of Justice. The carabinieri, barricaded behind the gates let go with a murderous volley. To cover the comrades’ retreat a bus was set alight. Despite everything, many were quite seriously wounded by the carabinieri. These casual ties and many others throughout the day were cared for at home; going to a hospital would have meant getting arrested. The official total included only 4 or 5 comrades amongst the wounded – whilst amongst the cops it was a dozen. But the reality was quite the opposite.

The attack on the Ministry of Justice was immediately succeeded by an assault on another gun shop at Ponte Sisto. A group of comrades tore down the metal grill and burst into the shop. But the confusion and rage did not give this gesture, a valid one given the circumstances, an organisational strength, which might have led to a better-armed defense of the movement’s destructive acts. The group, which led the attack on the armoury was not homogenous, it had come together at random in front of the gun shop. It was therefore a totally spontaneous action. The arms were dished out like sweets and in fact the majority were abandoned on the riverbank where the police picked them up the next day. The same thing happened a few hours later when the Casciani gun shop was attacked in the Piazza Cairoli.

Attacks continued to take place everywhere in the centre of Rome until well into the night – shops, banks, police stations, offices of multinationals. Proletarian anger didn’t spare anything, acting in a tempestuous, yearning manner hoping for an impossible and unforgettable revolutionary day.

The mass of people, dispersed and fragmented to the point that not even the most organised group succeeded in reforming, plunged into diffuse guerrilla actions creating spontaneously a nucleus which proceeded to attack a shop, a bank, a police station etc, splitting up immediately once the action was over. But the urban guerrilla plan was not realised. The movement had intended to put this plan into operation when it had occupied one or more districts in the historic core managing them as liberated areas. From this bastion attacks were to be launched on the sites of the institutions themselves.

Even if this project was not pure madness, the opportunity to extend it to the entire country was lost because it was a show of weakness not of strength, as appearances might have seemed.

In CASK, the Metropolitan Indian paper was the following:

“I attacked the gun shop at which I had carefully taken aim as we charged. Away with the false, away with the new. A flash, teargas, a bang? Bang they were shooting. Bang, bang you were firing but I couldn’t see you behind all those faces. Shit, but its heavy, a really heavy thing to have to run away. Get rid of it, asshole, get rid of it. Away with the false, away with the new. Splash – straight into the Tiber. Leave it there for another time which will never come – this was not the right moment. I’d been afraid”.

However, it did allow institutionalised repression more room for manoeuvre, to split comrades up and to isolate and repress nuclei of revolt. Above all the so-called proletarian and/or workerist parties who drew a vanguardist, militarist conclusion from this experience, preparing the terrain for the spectacle of terror, glimpsed already in the demonstration in Milan with the attack on the Assolombarda.

On March 14th the funeral of Lorusso took place. Hemmed in by armoured vehicles, 5000 comrades attended it in Bologna.

After the days of revolt the movement, bedevilled by arrests and a repression without precedent, suffered a brief setback. This left the terrain open to small terrorist acts against the black economy, sweat shops and the like. But, above all, it allowed the press to get all het-up over the actions of the major terrorist organisation. On March 12th, a police inspector, Ciotta, who sympathised with Lotta Continua was killed in Turin.

On March l6th, Rome University reopened. In the assemblies, which were held, the groupuscules were to display once more their institutionalized fixation. At the same time many comrades got all raffled-up in dull discussions like those about examination requirements. In the assembly held on March 22nd to prepare for the tripartite general strike (i.e. the 3 trade union confederations) agreed for the next day, a fight broke out between those who no longer wished to put up with the farce of “dialogue” (who were in the majority) and those who intended instead to persist with the groupuscule line.

On March 23rd, the counter-demonstration held by the movement succeeded in attracting a varied cross section but there weren’t as many as previously. There were a lot of truisms but little conviction – it did look as if the previous 10 days of confrontation had tired a lot ofpeople out.

Despite the fact the university had meantime been occupied by the police, confrontation continued to break out. It was “The Red Barons” themselves who were to incur the costs – Lucio Coletti, Albertor, Asor Rosa and others – were mercilessly ridiculed but weren’t physically harmed. However, these incidents were enough for the rector to justify closing the university for the nth time. It was a preventative measure to avert renewed attempts to reassemble. The movement had to remain physically split up. It was basically the same tactic that the PCI had adopted when faced with the school students. Continuing to occupy schools and less heavily targeted by repression, the students found themselves at the centre of the movement. The FCGI (young communists) succeeded in convening false assemblies, announced as belonging to the movement, which were controlled by its militants. The intention was to get suitable motions and resolutions passed in order to split the real opposition.

On April 1st the university was reopened. In the assemblies, which were immediately held in the Humanities Dept, a platform was approved comprising the following demands:

1) The police to vacate the university.

2) Depts to remain open from 8 in the morning until 10 at night, weekends included.

3) Courses of 150 hours duration to be officially recognized.

4) The 27 to be guaranteed.

5) Freedom of choice on examination subjects.

6) Evening university courses for workers.

7) University teachers to clock-on.

8) Teachers to be refused royal ties on photocopies and a fund for expensive books to be set up.

But in April sensational terrorist acts were to multiply (the kidnapping of Costa and De Martino, the assassination of the fascist Bubak in Germany). Given prominence in the media they were to be the focus of attention.

At the same time, repression continued apace; on April 15th the Government passed the Malfatti reform as if nothing had happened. On April 16th school students protested, the only ones still allowed to do so. There were more than 30,000 but they had to reckon on the attempts at recuperation by the FGCI and the groupuscules. The struggle was fought out by way of slogans and in the end it was all too obvious people were seeking a breathing space through the school students movement to co-opt protest into official channels.

However, it was the movement, which, on the contrary, recovered its breath. In Bologna, once the armoured vehicles had been withdrawn, several Depts were reoccupied. But a difficult moment came next day in Rome when confrontation broke out afresh. On the morning of April 21st many comrades gathered outside in the Minerva quadrangle in the university to confine the demands formulated by the movement on April 1st. First among these was the demand the police withdraw from the university. The members participating had fallen slightly even though the determination to struggle was always very much alive. What’s more despite having endured hard battles the movement was as sound as ever. It continued to proclaim the university a liberated, free space to be appropriated in order to have a physical space in which to organize actions and ideas – a space that allowed individuals and groups of individuals to gather together to confront one another. Otherwise they would remain isolated in their own private spheres or by the sectarian logic of the groupuscules. It was a requirement each was mindful of and which had formed the basis of the mass confrontations, which had taken place up to then.

The assembly organised a march around the university campus. It furnished a new pretext for Roberti, the rector, to order the police to once more evacuate the university. The evacuation took place relatively calmly. The comrades present at the university were not in the least bit organised to mount a confrontation. They left without offering any resistance. But after a brief period, around 3 in the afternoon, the comrades had once more regrouped in the adjacent popular quarter of San Lorenzo where some of the more organised autonomous groups were located. They, in their turn attacked the university citadel, or rather the police detachments that were holding it. Immediately a front was established in the access roads leading from San Lorenzo to the university, which was not more than some 100 metres away. The police reacted by firing blindly and taking aim at body height (on the walls of the Via dei Sardi the holes left remain a testament to that day). The comrades reacted by hurling molotovs from behind barricades of buses creating a wall of fire to prevent a furious police assault from claiming further victims. But the armed force of the institutions did not let up, sending in a squad of police cadets firing at will in the direction of San Lorenzo. The comrades overwhelmed by the hail of bullets, this time responded by taking aim at the police. 3 cadets fell to the ground, one of them was dead, another gravely wounded.

Attempting to defend itself the movement had killed a cop. He was a proletarian just like the proletarian comrades killed by the state. Ordered to butcher he had been butchered on the contrary. The movement did not have any sacrificial lambs; it was not directed by generals locked away in sanitized rooms. The movement expressed the desires and anger of each one of its participants and each one laboured and suffered just so long as proletarians like Settimo Passamonti, a police cadet were exploited and manipulated all on account of their proletarian status.

It seems an obvious reflection but in April 1977 it wasn’t even remotely taken into consideration and the movement harboured in itself a lot that was questionable. The logic of division was established.

In the assembly held in the Architecture School immediately following the confrontation the groupuscules and the militants clashed indulging in a party political game playing the majority of the comrades were totally estranged from. They were playing reactions game finally, which, on the following day was unleashed in all its forms.

It remains necessary however, to give some consideration to this episode, which up to now has been described and analysed only for self-serving ends. Either that, or, in the majority of cases forgotten about.

The police cadet Passamonti had been killed as an act of defence by the movement. It had not been part of a pre-ordained strategy. No one in the movement of ’77 believed that Lo Russo had been killed in order to precipitate revolt (we can leave this sort of speculation to the Red Brigades). In the same way, no one in the movement wished to kill a cop to raise the tempo of combattivity (it was already too high for its own good). The fact is this last incident signalled the beginning of an action/re-action spiral which was wholly unfavourable to the movement. But like now, at that moment one could not pose the question whether the person who had killed Passamonti had acted advisedly or ill advisedly. Because, unlike the bullet that killed Lo Russo, which had been fired by the state, the shooting in Rome had not been the act of a bunch of fanatics but of an opposition movement in its entirety. Everyone shouldered the responsibility now; there was no shifting the responsibility onto others. But that was scarcely what happened the following day.

In fact, drawing sustenance from this incident, a concentrated reaction without let up was loosed. In the 20 or so schools occupied in Rome, the FUGCI and groups let fly with an anti-autonomy hysteria. The comrades belonging to the movement couldn’t muster the strength to reply. Defying public opinion the few who defended the movement risked being lynched. The quality newspapers like ” Il Messaggero” printed terrorist editorials like “it’s necessary to isolate them”. Amidst the general applause of all the institutions and their information channels, the Minister of the Interior, Cossiga, declared, “the State will respond with armed force”. In Rome, police H.Q. banned all demonstrations until May 31st.

But in San Lorenzo, the proletarian quarter, which was most involved with the revolt, the conflict with the PCI became very violent. More than half the militants and cadres of the local communist party quit to join the autonomous collectives.

On April 25th, liberation day, the PCI asked that it be allowed to stage a demonstration in contravention of the banning order. The authorisation to do so arrived two days after.

On the same day, the university senate had decided to reopen the university on May 2nd.

Meanwhile, the spectacle of terror continued, which the newspapers gave particular prominence too. In Turin, the Red Brigades killed Croce, a barrister and president of the bar. In Rome, the head of the Law Dept, Rosario Nicolo, was kidnapped and held to ransom.

In Bologna, where a meeting of the movement was to be held on April 29th / 30th, the university was closed and the town garrisoned. The implicit aim was to make sure the meeting was a failure. Many comrades from Bologna were in prison or on the run. It was a trying moment and in the course of the meeting, which was poorly attended, the weakness of the movement was obvious. The analyses on offer there, even if they were not totally wrong, were based on unreal presuppositions.

Even the group Zut/Atraverso, which had brought out “Rivoluzione” and which, during the days of revolt, had expressed a high degree of lucidity, indulged in overestimation. Confusion and the disjuncture between the movement and reality increased.

In Zut/Atraverso: “From Lyric to Epic (avoiding the tragic)” there appeared the following:

“After the trouble in March, the Italian situation was revealed in all its dramatic intensity to revolutionaries. There is no doubt this time about it, we are in a revolutionary situation – it is not just a phrase. What do you mean by that? We are going through a moment of historical rupture in the course of which the entire basis of existence for the masses, of the masses, of the relationship between people and between classes, is transformed. In the impenetrable web of everyday life, in the tension of desire, in material needs, in the form of life, in the conditions of production and reproduction – what’s specified in the Winter/Spring of 1976/’77 is an extraordinary large nucleus. No one can pretend not to see it nor believe anything will remain the same”.

That revolution can come about as a result of acts carried out by a marginalised minority of the population, however combative, is an illusion. Not that the French bourgeoisie or the Russian working class that carried out the greatest revolutions of modern times were a majority of the population. They were a minority but they were central to production even though in a minority. The Italian marginals who made up the ’77 movement were in fact excluded from the process of production and therefore as a result, without any influence on capitalist development. This does not mean they did not express a real situation of struggle and opposition. Only that, however much the movement was committed to creating a revolutionary situation, the support of living labour as the revolutionary subject – even if not the only one – becomes necessary to the movement. It was this premise, which the movement had radically inverted. As postulated by the movement of marginals the aim was to encircle the socially productive structures, thereby causing a rupture. However, the existing historical conditions were far from creating a rupture of this order.

In the assembly in Bologna this distance became tangible. The loudest voices were those of the militarists and the one fact emphasised by the bourgeois press as solidarity with terrorism voiced by some sectors of organised autonomy from northern Italy.

On May 1st in Rome during the official national demonstration, the movement clashed with union stewards. Counting on the dissatisfaction of the Lirico delegates and the workers from the south, especially from Italsider in Bagnola, the aim was to foment a division in the ranks. Though in a minority, comrades from autonomous collectives clashed with the stewards, then were charged by the police. At the same time, workers from Bagnola attempted to rush the speakers’ platform. However, it passed off without an echo and it was all over in a few minutes.

It was the beginning of the minority phase of the movement, which after the tragic May Days was no longer to find the strength to construct a revolutionary project.

In fact it was during the month of May that the repression thrown against comrades reached South American proportions without there being the pretext for it.

At the beginning of the month the DC (Christian Democrats) launched a campaign to reintroduce police detention for 48 hours, while at the judicial and informational level the idea of a plot was hatched. Judge Catalonalti (PCI ) in Bologna issued his first interrogation orders imputing the March revolt to certain comrades. The newspapers repeated this claim putting the revolt down to a plan worked out in advance by organized autonomy groups.

In this climate of a witch hunt an attempt was made in Rome on May 12th to hold a peaceful demonstration to celebrate the victory of the referendum on divorce in 1974. The police order banning all demonstrations in Rome from April 22nd was still in force. The demonstration on May 12th that had been organized by the Radical Party had been conceived as a festive occasion. A stand had been erected in the Piazza Navona on which musical groups could perform. It was an occasion on which comrades could meet up in the face of police terror. There was also the possibility on this neutral occasion of resuming a majority discussion discourse.

But on this occasion with deliberate premeditation the state organised a day of terror. On this day open war on every form of opposition announced a few days previously by Cossiga was expressed in all its brutality. Unfortunately, this time there were no armed comrades ready to defend the main body of comrades. At a point when the weaknesses were two fold – at the level of ideas and organisation – the movement was attacked frontally. May 12th was to actually resemble, in form but not in content, a demonstration in Chile the previous year.