As the world is ending, not quickly like in a Hollywood movie, but slowly, each day bringing a new agony and a new attempt by the world to find balance, it’s thrown into relief how all our commonsense ideas of risk and ethics fly out the window. What does it mean to stay safe in a world that is ending? What is our measuring stick for risk when the forecast for how much life the next world will sustain is pessimistic? And what does it mean to be ethical, or just decent, in a world that is being murdered by monsters who are far more selfish, and who cause exponentially more harm than the villains in the most gruesome horror film, and yet unlike those villains are completely normal, vindicated, and even celebrated within our society?

I think we can simplify these questions in a way that may provide some perspective.

Which future would you rather face?

Having to spend between one and ten years in prison

OR

not going to prison, but living in a world in which:

- you and most people you know will, by the age of 50, probably get cancer, heart disease, diabetes, an auto-immune disorder, or a painful chronic illness that no one understands (with all the suffering and likelihood of death that accompany those conditions)

- you, your immediate family, and your closest friends will have a roughly 10% – 50% chance of experiencing a high death toll extreme weather event or acute famine, and possibly dying in it

- if you have family and loved ones from outside Europe/Australia and North America, they will probably face a 50-99% chance of having to face lethal weather events and famines multiple times, killing many of them

- any natural area that you have ever loved will be forever altered by mass extinction, mining, drought, or other causes

- you would have to sit by and watch as the political institutions, financial institutions, and corporations most responsible for all this suffering gain ever more power over your life and your surroundings, never being abolished, never being held accountable in any meaningful way.

Now let’s assume that the bad things described above—relating to death, disease, extreme weather, mass extinctions—are going to happen no matter what. In fact, yes: let’s assume that. We’re not speaking hypothetically right now. This is a realistic assumption. All the scientific models that have been validated and refined over the last decades predict that we are on a collision course for that level of suffering and death, or worse. In the parts of the world that are on the cutting edge of the apocalypse, those conditions already pertain.

So now let’s come back to our hypothetical scenario. First, the scenario’s realistic foundation:

Every year for the foreseeable future brings with it the grim certainty of skyrocketing death rates, disease, famine, mass extinction, loss of habitat, and the disappearance of entire ecosystems.

Now, the choice. Would you rather:

- face all this harm and suffering, within the approximate probabilities named in the first bulleted section, but also

- take illegal actions against the structures and institutions responsible for all this suffering, and by doing so assume a less than 50% risk of one to ten years in prison

- know that with all the other people also taking forceful action, ecocide and genocide become less profitable, and those in power lose some or all their power, whereas the rest of us, as well as the generations to come, gain a partial or complete ability to organize our communities and tend to our ecosystems in a way that prioritizes healing

OR

take no action other than symbolic protest, avoid the risk of prison, but also do nothing to diminish the power of the world eaters. With nothing to hold them back, the apocalypse becomes even more brutal, and the future you face includes:

- hundreds of millions of humans dying every year from famine, lack of clean water, pollution, extreme weather events, and genocidal warfare resulting from these scarcities occurring within a competitive politico-economical framework

- you and everyone you know facing a significant decrease in life expectancy, as the entire human population decreases between 10%-80%

- the likelihood that you and the people you care about the most have to survive or are excruciatingly killed off by famine, cancer, diarrhea, tropical diseases, heart disease, untreated infection, wildfires, floods, or warfare

- having to obey the increasingly dictatorial authority of the political and economic institutions that are directly responsible for all this suffering, or even worse dictatorships that arise as society falls apart but people just watch it all passively

In the above scenarios, which offer simplified but accurate versions of the hidden choices we all face every day, what does the risk of prison have to do with the apocalypse and how extreme it gets?

Actually, everything. To understand why, there’s some official history that needs to be refuted.

When we learn the standard history of civilization, revolutions are never mentioned until the Age of Reason and the supposedly reasonable revolutions of slave owners, colonizers, military officers, and businessmen in France and North America. Prior to that, we may hear of quite a few earlier civilizations that mysteriously collapsed. Or, we may get spoon fed a tale of continuity from Mesopotamia through Egypt to Rome and the Holy Roman Empire and Spain and then modernity, with everything beyond the shadow of the State (or in the latter version, beyond the shadow of so-called Western states) completely ignored.

In the years I was doing the research for my book, Worshiping Power: An Anarchist View of Early State Formation, I could not find a single example of a statist society that collapsed, that just fell apart from some logistical inefficiency, spiraling warfare, or local ecocide perpetrated by the ruling class. I did come across multiple “mysterious” collapses that were quite clearly caused or at least helped along by lower class revolutions, and after these revolutions people’s quality of life usually improved. As for the other collapses that do remain mysterious, in every case I came across evidence—inconclusive but nonetheless strong—that popular uprisings combined with massive abandonment (back in the day when there was a frontier beyond which State power did not reach) helped tip the balance of power. Yet the vast majority of academic sources I plowed through—historians, archaeologists, paleoecologists, and anthropologists from fifty different decades, twenty different countries, and a dozen different schools of thought—refused to even mention the concept of revolution or to portray the lower classes as a group capable of agency or even thought.

So: revolution. It’s been with us as a possibility as long as the State has. Accordingly, in our present scenario, I am talking about us rising up against the power structures responsible for ecocide and genocide, and taking effective action against the institutions and infrastructures that cause us the most harm.

The question of the law, obviously, is a joke. The law is a weapon in the hands of the ruling class. They only follow it or deploy it when it suits their interests. And if we take effective action against them, they will try to punish us regardless of whether our actions are technically illegal.

So I’m not strictly talking about taking illegal action: I’m talking about saving ourselves from immense harm, which most people would consider an ethically valid basis for action.

For now, let’s leave aside the ethical question of, how many people complicit in mass murder is it okay to kill, provided they are still engaged in mass murder and we’re not punishing them for harms that are no longer ongoing. (I might pick that question up in a future newsletter.)

At the moment let’s just imagine the destruction of things that have no feelings and no existence outside of their status as tools for extraction, domination, and despoliation: pipelines, mines, highways, airports, prisons, mansions, drilling installations, facilities related to the police and military, cash crop and monocrop operations, golf courses, grass lawns, cell phone towers, useless-shit factories, chemical and automobile and weapons manufacturers… the list goes on and on.

We know from past experiences that sabotage campaigns are exponentially more likely than protest to lead to the cancellation of new oppressive infrastructures being built. Sabotage campaigns together with protests are even more effective, especially if those protests focus on blockades and the total rejection of those in power rather than the overtures to dialogue. Regardless, protests, blockades, and sabotage all put us at risk of arrest and imprisonment.

About that risk though. I tossed out the figure of a 50% chance of going to prison. That was intentional, because I think if we are going to take big risks for a revolution, it is much healthier and more sustainable if we face up to those risks and assume the worst will come to pass. If we can imagine ourselves dealing with the consequences and surviving, prison and the police will already have lost most of their power over us. But realistically, the actual risk is closer to, and probably below, 1%, if we follow some basic security practices. Significantly, the actions that may feel the safest if we are inculcated in all the delusions of a liberal democracy, are actually the riskiest.

This has certainly been true for me. In my life, I have been arrested four times. Those four arrests earned me (in order)

- six months locked up in county jails, maximum security prison, and minimum security prison, where I faced various forms of violence from guards and snitches;

- a weekend in a temporary detention facility in conditions that technically qualified as toxic;

- a week in jail, a deportation process lasting two years in which I had to remain in the country and check in at court every two weeks but was not legally allowed to work, and the whole time I was under the threat of a permanent ban, which would mean never being allowed to return and see loved ones;

- and a quick night in jail, respectively.

The first three arrests—the ones with the worst consequences—were for some of the most peaceful actions I have ever participated in. The first was civil disobedience, the second was a legal protest (in fact it was the mass arrest that was illegal, and if I’d had the patience to follow up with some noncommunicative lawyers I would have gotten a huge payout a few years later, in part for the illegal arrest and in part for the toxic site where the holding pens had been set up). And the third was also a legal protest, though it took two years on provisional release and a court case to prove it (there was, um… some disagreement about what constituted “public disorder” and what constituted an “explosive” in the eyes of the law, and it took a good lawyer and favorable witnesses to win that dispute).

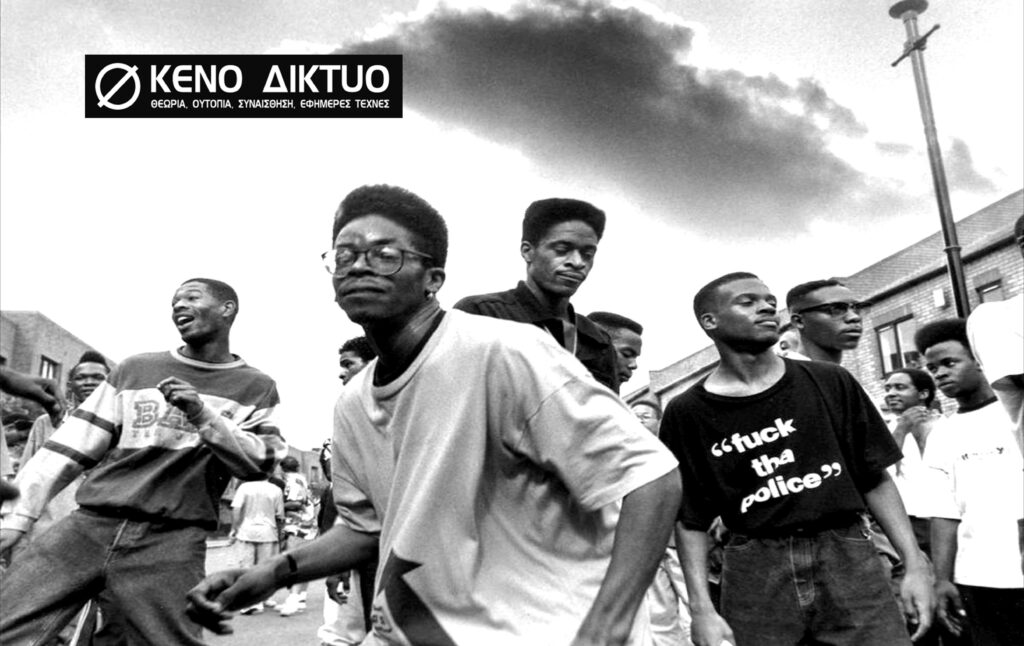

The fourth one actually was an illegal protest in which a number of neo-Nazis and cops got assaulted and even injured, and some property got smashed. My friend and I weren’t assuming any additional risks aside from going with the flow, but going with the flow is its own risk, and we didn’t hightail it out of there fast enough when the signs made it clear that that was the move. However, police couldn’t pin anything on any of the people who got cornered and mass arrested. It was too difficult for them to gather specific evidence, because of the chaos factor, because people weren’t civil, because of all the movement and pandemonium plus a modest amount of destruction. Of course, police don’t needevidence to lock people up in prison, but in a democracy they do need to calculate how much they can stray into the legal terrain of the state of exception. In this case, it would have been harder for the pigs to sell since there wasn’t enough disruption for the media to create a major political scandal or mobilize fragile bourgeois sensibilities enough to justify locking up anyone who had anything to do with the protest. So they let us all go.

Now let’s talk about all the things that aren’t showing up here, all the risks that never resulted in arrests. Or, more appropriately, let’s talk around them. There is an unavoidable inequality between civil disobedience, on the one hand, and on the other the continuum of sabotage, collective self-defense, counterattack, and insurrectionary action. The State will go to far greater lengths to repress or eliminate those they suspect of carrying out forceful actions, and also those who vocalize their support for such actions and the revolutionary culture they belong to.

What’s more, the State proactively organizes society to preempt the capacities we need in order to struggle wisely, like the ability to tell stories and create collective memory. We are shaped as isolated individuals dependent on the dominant institutions for any sense of history. More often than not, they just spoon feed us entertainment to fill the hole where our sense of history should be. And as we know, repression skews sharply in favor of nonviolence: it is far riskier to tell the stories of sabotage, of insurrection, of combat. I won’t be sharing any such stories in this newsletter. Immediately, I can hear in my own head the cynical insinuation that I’m probably just some hypocrite who only writes about this stuff. Which is okay. We need to learn to deal with far worse forms of baiting and harassment.

The most important thing is on the one hand not to respond from a place of ego, not to worry about curating a reputation for being a daring revolutionary, and on the other hand to pay close attention to anyone who mocks or belittles others in a way that would encourage a culture of people having to show off or insinuate their illegalist credentials. And always remember the maxim: you don’t have to be a cop to do a cop’s work. (Don’t spread rumors about people you suspect of being infiltrators or snitches: the cops themselves benefit from rumorology and often spread false accusations against others; instead, share constructive criticism of harmful forms of communication and conflict/avoidance.)

Stepping back from our individual egos and sinking into our collective body, what any one of us can attest to is that there have been tens of thousands of banks and cop shops smashed or burned, pigs and fascists beaten up, government buildings attacked, pipelines and mines sabotaged, construction and clearcutting equipment destroyed, research facilities torched, labs liberated, secrets leaked, useful or valuable goods stolen, and frauds committed, and those who have done prison sentences can best be counted in the hundreds,1 with many of those being people who got framed but didn’t actually do anything.

In other words, we are often the safest when we play it dangerous, as long as we are careful, as long as we use precautions or make smart interventions during chaotic moments, as long as we discourage a culture of bravado, self-isolation, rumor-spreading, or snitching.

And to zoom out for a moment, no one on this planet is safe until we can nourish an ethos of collective self-defense against the institutions that are threatening and harming us, smashing their gears so they cannot function anymore. What use is it to speak of survival if we have no practice of fighting back against those who are killing us? There is room for all of us, but we need to figure out what we can contribute and what it is we still need to learn in order to be a vital part of the webs of solidarity and mutual aid.

Thanks for reading Surviving Leviathan with Peter Gelderloos! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A revolution is not comprised of tactics alone. If we let ourselves get turned around by impatience, desperation, avoidance of criticism, loss of historical memory, if we divorce our strategies from our goals, our visions, and our ethics, we quickly become our own worst enemies. Nonetheless, it doesn’t hurt to proliferate certain tactics, to imagine what a better place we would be in if people realized it’s well worth the risk to attack the infrastructures that are spewing out death, poisoning our futures and our present. What a better place we would be in if people responded to our learned helplessness, to this hegemonic hopelessness, with a thought, a certainty: how many miles there are of unprotected power grids and pipelines! How many bulldozers, construction sites, and offices of evil institutions have no more protection at night than a camera that will log nothing more than a time and a masked figure, unidentifiable! How many of us there are, and how hard we are to surveil when we leave our snitches at home, when we don’t take our phones and other tracking devices out of the house with us!

How powerful, when we realize that we are powerful. How frightful, when we remember that we can be vengeful. How grounded, when we learn to integrate our need to fight and to heal. How inspiring, when we understand that all the walls and cages and cameras and militarized police forces of this whole prison society are there to protect the powerful… from us.

Sooner or later, the odds will flip, and our probabilities for health and survival will begin a slow ascent, and the odds on the plutocrats and police will face a sudden plummet. That moment? Collectively, we decide when it arrives.

1

The approximation—tens of thousands of actions, hundreds of imprisoned—is based on, roughly, the last ten years in the half dozen countries I’m most familiar with.

_____

SOURCE: https://petergelderloos.substack.com/p/ethics-risk-apocalypse