Last night an anarchist from Lebanon gave a report on the situation in Egypt at our social center , and I wanted to pass this information on to English-speaking comrades. This is a series of notes extracted from the talk, highlighting questions anarchists who have read mainstream coverage are likely to have about the situation.

The person who gave the talk has been involved in organizing solidarity with people in Egypt, and as a part of the talk he skyped a friend in Tahir Square so we could ask her some questions directly.

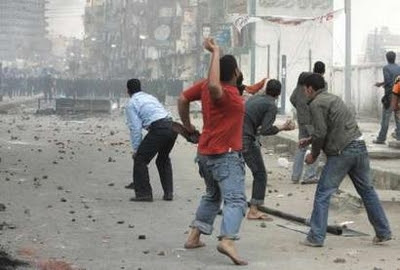

The revolution in Egypt has been spontaneous and self-organizing, spreading from Cairo and other major cities to the countryside, where in some areas Bedouins took up arms against the police and the military. The revolution has not been peaceful, but in most cases it has been unarmed, owing to the simple fact that most people don’t have recourse to weapons beyond stones, clubs, spray paint, and molotov cocktails, all of which have been used against police forces in abundance. (The spraypaint is for the cops’ visors, and once they have to lift those up in order to see, for their eyes). When government paramilitary thugs attacked the protestors on Tahir Square (the incident initially described by Western media as a clash between Mubarak supporters and Mubarak opponents), they were expelled with violent force.

Because Egyptians have lived under dictatorship for so long, only the elderly have any experience street fighting, so a major form of solidarity by comrades in other countries has been the creation of informational flyers in Arabic explaining what are essentially Black Bloc street tactics. Given the participation by anarchists and anti-globalization activists in this direct aid, the reference to the Black Bloc is not intended as metaphor or exaggeration.

Another major form of solidarity was reconnecting Egypt to the internet. Either through personal connections or even in many cases faxing infosheets to random fax numbers in Egypt, hundreds of people outside Egypt showed protestors in Egypt how to get around the blocks and reconnect to the internet.

So far, comrades in Egypt have generally turned down offers of fundraising so the regime could not say the rebellion was being funded by European anarchists.

Participation in the uprising has been general and multigenerational. In a country of 80 million, 3 million have regularly come out in Cairo and many millions more in other major cities. The rural population is less likely to mobilize in central locations but they have participated in the uprising in other ways.

Many Western media outlets have tended to focus on male participation in their images, but from the first day many women have participated in protesting and street fighting. The comrade we talked to in Tahir Square is a queer anti-authoritarian, so when she says “everyone [over there] is united,” we are inclined to interpret this differently than if a union representative had said the same thing.

The masses gathered in Tahir square self-organize through an assembly that has issued communications and organized the feeding of the people there, the cleaning of the streets, and self-defense from government thugs. Multiple times, foreign media have quoted spokespersons from youth-organizations who claim to represent the protestors. Every single time this has occurred, the spontaneous assembly of the square has released an unequivocal statement that they have no representatives. Emphatically, no organization is behind the protests or has been particularly relevant within the protests. Many factories and workplaces are also organizing committees.

The Muslim Brotherhood has been on the streets along with everyone else. Their representation is no more than a quarter of all the participants, and they are not in a particularly strong position. Either cynically or because they too are caught up in the insurrection, they are making no move to increase their power or lead the uprising, nor would they be able to do so. The comrade on the square emphatically stated that the fear of an Islamic takeover in Egypt is the paranoia of the Western media and nothing more. The discourse of the protestors’ spontaneous assemblies, which is the only power in the country next to the military, which has chosen generally not to intervene, has consistently stressed goodwill and solidarity between Muslims, Christians, and atheists (in a cultural context where usually the existence of atheists is never even mentioned).

Regarding the possibility that Baradei will be the next leader of the country, the comrade said this is unlikely since he has no legitimacy among the protestors as he did not participate in the insurrection (although he could easily be made a minister).

The demands of the protestors are overwhelmingly for rights and democracy. A common demand is for elections within nine months, with no power-holder in the transition period being allowed to run. The attitude of the protestors and their intense experience with self-organization suggests at least the possibility that Egyptian society will not go back to sleep after elections, but that there is potential for increasing struggle.

The comrade in Tahir square said that overall, they lack know-how in terms of self-organizing and political visions, as Egyptian society has been asleep under dictatorship for decades. She invites comrades to come visit and build international connections and solidarity.

Currently, everyone is walking around in a state of euphoria, relaxing after 18 days of combat, partying, eating, sleeping. People there feel the Arab uprisings will continue, with Iran being the favored bet for an uprising after Algeria.

Soon, there will be a call-out for an international day of action against Orange and Vodafone or connected companies (these were involved in turning off the internet to Egypt). Diversity of tactics encouraged.

Theoretical/Strategic points I want to stress:

About the nature of insurrection as a force for desubjectivation. People who participated in the uprising blended into one multifaceted, solidaristic whole. This even included people whose class relation should have trained them to view the uprising from the outside. In one anecdote, an Al Jazeerah reporter in the middle of Tahir Square, on a live broadcast, spouted exuberantly “We’re going to win! We’re going to win!” The studio anchors questioned him, “Who we? Aren’t you the only reporter in the square?” “The people! The people! We’re winning!” “You’re there on assignment! You work for Al Jazeerah.” “Oh, oh right.”

About the argument between dual power and insurrection. Once again, the opportunity to break with the past and create something new comes not from building up alternative infrastructure but from a violent and spontaneous insurrection. Also once again, the lack of visions will make the emergence of anything truly new impossible. The comrade on the square told us the day Mubarak stepped down, “We have a lot of work to do.” When asked further what she meant, she explained that the question every single person was asking themselves, and also a question people who participated less were directing to people who participated more, was: “What now?” And the overwhelming conclusion was that they had no idea. Democracy was the major demand because it’s the only thing people know about that isn’t dictatorship.

Speaking with people in Greece, I’m also aware there was a major “What now?” moment there, around Christmastime (December 2009). Interestingly, that did not seem to be the case in Oaxaca, where surviving indigenous cultures regularly promote visions about another possible worlds. Perhaps the greatest hole in insurrectionary praxis is the disdain for visions, and the enfuriating inability to distinguish between visions and blueprints (if you’re still unsure, take some psilocybin, then read Parecon, and jot down the differences in your journal).

What made this reportback possible, and what enabled international solidarity to the people in Egypt? In this case as in nearly all others, language and personal contacts. The comrades in our city only have access to direct information, instead of the bullshit in the media, because one of our comrades speaks Arabic as well as the language we speak, and he has friends in Egypt because he has travelled there.

Currently, anarchism is only a force in Europe and the Americas. Any anarchist who believes in international solidarity is consigning themselves to helplessness if they do not learn other languages and travel to other parts of the world to make friends. The argument that travel is an economic privilege, while it has some truth, leads to an ironic interaction with the actual situation: the vast majority of international anarchist relationships exist thanks to comrades from poorer countries immigrating to richer countries and bringing their contacts with them.