VOID NETWORK ANNOUNCEMENT- In the case of Ukraine – as in any inter-state rivalry – we can only assess the facts after placing them in a broader historical context.

From the historical process of colonialism, which has been at the forefront of the development of the modern world, and the two world wars, to the Cold War, and the many local wars around the world (Vietnam, Yugoslavia, Falklands, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria), inter-state conflicts have been rooted in the attempt to extend or maintain the domination of one power over another. Typically, major powers claimed to control territories that extended beyond their immediate territorial (and culturally defined) sovereignty and jurisdiction. In this effort, they sometimes attempted to wipe out entire peoples and cultures – as was the case with the indigenous populations in the Americas, Australia and Africa – sometimes they fought each other – as in the two world wars – and sometimes they waged wars by proxy – as in the case of the Middle East and South America.

Therefore, it is not enough to see the case of Ukraine only through the actions of a Russian authoritarian leader, nor through the prism of a violation of international law. This is for three reasons:

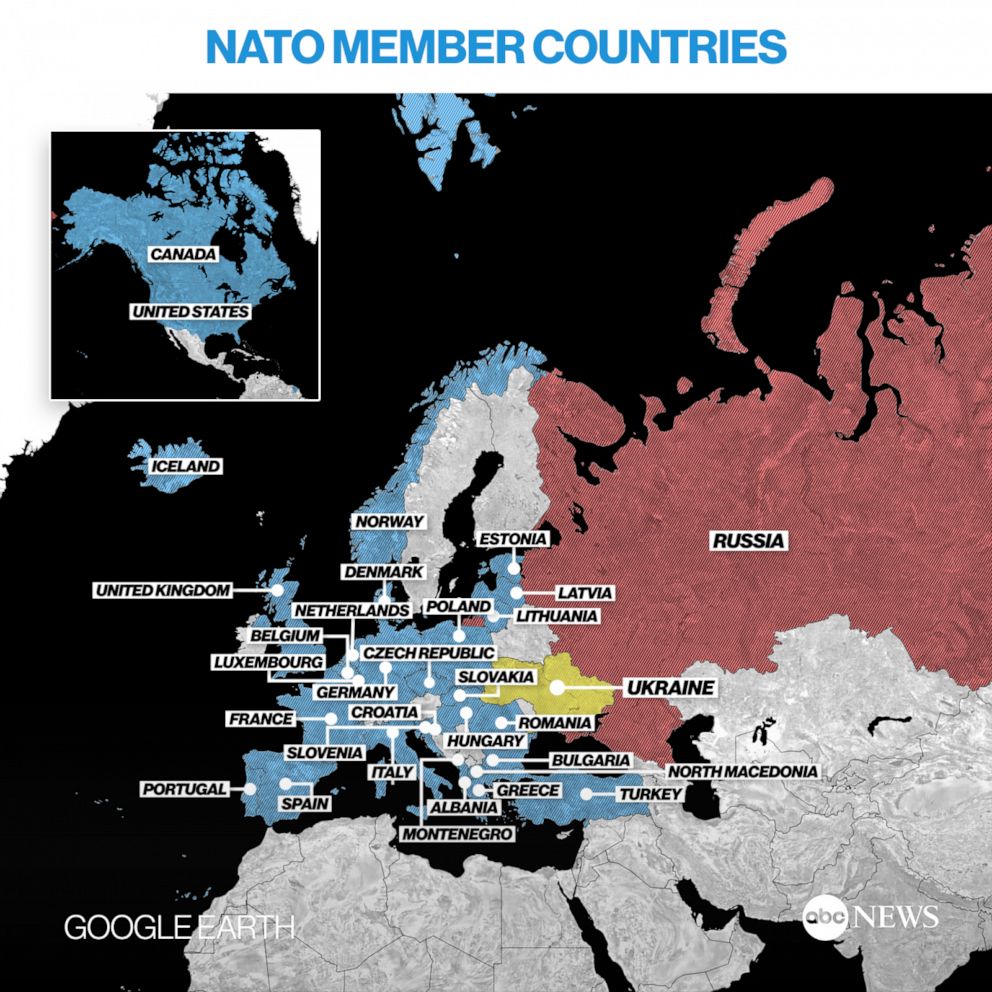

First, because we cannot ignore the presence of NATO, which after the fall of the USSR and in the context of the emerging “neoliberal consensus” became both a military vehicle of consolidation and a police institution against centrifugal forces. Thus, on the basis of the role of the US in this new phase of “globalisation”, NATO became essentially a mechanism for consolidating the US-led empire of capital. To put it in paradigmatic (and largely rhetorical) terms, what exactly did a supposed “defense alliance” do by bombing Yugoslavia without the approval of the Security Council, carrying out one of the largest military operations on European soil? How can it be denied that Yugoslavia was devastated by NATO for the interests of the US and its “New world order” doctrine? Did that event constitute war – at least some form of war – or a “special military operation”? Even if it is not just a powerful military instrument of the Americans, NATO cannot be conceived outside the imperialist policy of the USA. It is worth noting, in this context, that the inter-state relations between Russia and the US over the last 30 years have been largely structured by the initial assurances of the NATO alliance that they did not intend to expand the alliance eastwards and the gradual breaking of these promises. That these assurances, as Spinoza reminds us, have no substantive force outside of actual power relations and their historical unfolding points to the heart of the matter (something we will return to).

Second, war between states in its modern form tends to involve the clash, and therefore the intensification of two or more nationalisms. This is because nationalism is the ideology of the contemporary nation-state and therefore one of the inevitable languages of justification for a state of war. As a determinate historical form, the modern state relied on war for its birth and the organization of society on the scale it proposed: the boundaries of the state as a legal order of sovereignty to coincide with the geographical boundaries of the nation. It is truly an outrageous idea that continues to leave humanity blood-drenched, to produce cultural difference, and to systematically lead to tragedies and ethnic cleansing. Linking soil with blood: a genius German conception! Even the republican conception of the nation that draws on the American and French revolutions, and which admittedly provided the language for an entire revolutionary tradition, inevitably tends, after the consolidation of the state form, to become a language of legitimation of domination, exclusion, violence and expansion.

In the case of the Greek state, nationalism led to the tragedy of Smyrna with the help of the great fantasy – yet one with entirely material consequences – that we called the “Great Idea”. Nationalism is also responsible for the tragedy that Cypriot society has been experiencing for so many decades on both sides of the island. Rhetoric about living space was indeed used by Hitler and is now being used by Putin. But the difference is that the former was a Nazi and as such burned anyone who was not ‘of aryan race’ in the crematoria, while the latter is the authoritarian leader of a country that sacrificed 20 million people to stop the Nazis. The difference is staggering. And it is a difference of content as much as of form: for all the autocracy, corruption and constant human rights violations that define the dysfunction of official institutions and the huge democratic deficit in the country, Russia is not a fascist state. This, of course, does not justify the Russian invasion of Ukraine, because whatever the context, it is an invasion. But we must be strict in the analogies and comparisons we make because they determine our perspective and therefore our political stance.

It is also worth pointing out that the identification of Russia with the USSR is untenable, at least in the ideological field. On the other hand, on the geopolitical and economic front, things are clearly more complex, since the USSR (from one point onwards) became to a considerable extent the continuation of the Russian state; thus the Russian Federation, together with its satellites, inherits the treaties left by the USSR. Putin’s rise to power is also the expression of this “continuity of the state”, against the aggressive (and destructive for the plebeian masses) disintegration that preceded it. Besides, apart from some fascists like Georgiades, who else considers “the communists” dangerous and still dreams of exile (really, “dangerous” for whom?). Despite the special symbolic weight of communism in the construction of various identities and perceptions, all countries, in one way or another, move to the rhythm of the capitalist organisation of the economy and society. So does Russia. Within this global system, nationalisms continue to develop and the great powers continue to compete with each other in national terms, without reference to the political-ideological differences of the past. The competition today, similar to some extent to the imperialist competition before the First World War, is about power within the globalised capitalist system. But political-economic competition is always conducted through a multitude of ideological-cultural mediations, de facto historically determined.

Thus, it is difficult to abandon the idea that the cultural representation of Russia in the ‘West’ passes through the imaginative conception (and constitution) of difference. At the state level, the hostility towards Russia clearly has as an objective basis, Russia’s independent hegemonic geopolitical and economic role and ambition (the political expression of which is precisely ‘Putinism’). Also, in the social imaginary (as mediated, of course, by spectacular media representations) the emerging suspicion and hostility towards Russia is due to Putin’s current attempt to regain the country’s old imperial power. On both (related) levels, however, the hostility is fueled by the stereotypical construction of Russia as a threatening authoritarian power coming from the barabaric East. It is within this cultural construction of otherness that the reflexive and endemic anti-communism that some Western military officers and diplomats have long since internalized, finds its functional place.

In this intense interface between the political and economic aspirations of the hegemonic centres and their ideological investments, obsessions and prejudices, international law can only be respected on a case-by-case basis and according to the interests at stake – sometimes invoked and sometimes ignored. Liberals and social democrats of all stripes and tendencies will retort that there is a whole material system of rules, deliberations, agreements, decisions, institutions and bodies which produces what we call ‘international law’, and which has a regulative role; even when it is ignored by some states, its actuality allows us to criticise this attitude while at the same time giving to Right an institutional and therefore practical status (i.e. clearly defining what ‘ought to be done’ and ‘how’ it can be done).

This is certainly not the place for an extended discussion of international law, which de facto presupposes a broader analysis of law in general. Its violation, however, as a fact systematically carried out by the powerful, makes the interpretation of reality on the basis of international law alone a symptom of a normative formalism that does not help explain a complex situation and the dynamics it contains. Founded on the liberal legalist logic that systematized it, international law is utterly incapable of both regulating the actual relations of states and providing a theoretical basis for understanding them. The same can be said differently: vis-à-vis ‘powerful players’, international law is a weak tool and therefore, especially in times of crisis, it is not sufficient either to dictate and organise the practical activity of the powerful, or to take it as the main unit of analysis in understanding complex historical processes, that shape inter-state rivalries and international balances. Unless we want to become the unhappy consciousness of this world, along with liberals and a significant part of the Left.

The third reason why we need to be careful in our perspective is related to the collective self-identifications and the character of Ukrainian nationalism. It helps us to understand the complexity of Ukrainians’ perception of the Russian invasion, i.e. ultimately how they perceive the ethnic ‘self’ and the ethnic ‘other’ in this particular case. This clearly makes the way in which the invasion of Ukraine is presented by Western officials and the ‘Western’ media very problematic, i.e. as an attack by a foreign power on a fully distinct ethnic society. The empirical data that anyone who knows anything about Ukrainian society can cite suggests something quite different.

Between Russia and Ukraine there is a strong cultural affinity, with deep historical roots, reaching back to the very constitution of Tsarist Russia as the hegemonic political form of the Slavic ethnic group. Even today a large percentage of families in both Ukraine and Russia are mixed, and kinships spread beyond their borders. To this significant part of the population, this particular war seems rather like a civil war. Especially in the east, where there has been secession, a large percentage of Ukrainians have no particular problem with the political attachment to ‘Mother Russia’, which is why Russian forces initially met little resistance by advancing into the country.

On the other hand, colonial control and inequality has been a key index in this complex historical relation. Naturally, the Ukrainian nation-state de facto established its identity in against Russian domination, of which the USSR period was considered a part. This “anti-Russian” national narrative intensified after the events of 2014 in the country, when the balance was disturbed by the violent political shift towards the West and therefore NATO. In this context of geopolitical and economic restructuring, Ukrainian nationalism is becoming radicalized and seems to be gaining traction in the social sphere. Even so, until recently it is doubtful whether, outside the extreme nationalist circles, of which the neo-Nazis of the so-called ‘Right Sector’ (Pravyy Sektor) with their black and red flags or the even broader and more diverse ‘Azov Battalion’, which is part of the Ukrainian national army, most Ukrainians wanted to fight against Russia (which is also true in reverse). This is precisely what Russian expansionism is now decisively reversing, further fomenting Ukrainian nationalism.

In ‘Western’ media and in the mainstream discourse in general there is a deafening silence about the internal political balances and collective identity in Ukraine. In fact, the attack on Ukraine strikes at the pan-Slavic narrative – a central feature of ethnoromanticism there – replacing it with nationalist hatred. Is this not contradictory to the fact that Russia appears to be the main political exponent of this ethno-romantisism? But also, the hybrid character of the collective, national identity in Ukraine, or the fact that it is presented as ambivalent in terms of the distinction between ‘Russian’ and ‘Ukrainian’ nation and the related sense of collective belonging, is a catalyst for the attack. If, in terms of ethno-cultural relations and collective identities, similarity and affinity rather than ethnic difference prevail, without one group necessarily identifying or assimilating the other, the attack from Russia’s perspective ceases to be seen as an invasion. If, even more than in other countries of the former Soviet Union, Ukrainians are, in a sense, in an identity transition, since the process of Ukrainian nation-state building is unstable and ongoing, the attack on Ukraine may have had as an intrinsic purpose to radically interfere in the process. And the instability of the Ukrainian political system and the dysfunction of its democratic institutions actually contributes to this attempted rapprochement with Russia (for a country whose president is a former actor who played the president in a Ukrainian T.V series [!]). Therefore, in the face of the project of stabilising Ukrainian institutions and democracy within the EU. -which seems to have been the main claim of the 2014 protests and which necessarily took the form of anti-Russianism, thus opening up space even for nationalism drawn from the collaborators of the Nazi invasion- Russian imperialism, faced with the very real danger of Ukrainian attachment to NATO (i.e. the expansion of the latter), responded with an operation to strengthen the link with Russia. Of course, since the Russian surprise didn’t last long and the war drags on, it’s hard to see how a regime change could bring anything but instability.

Here it rather seems that we have two sides – Russia and the ‘West’ – that fear and perceive each other as a threat in terms shaped on the one hand by the history of conflicting expansionist nationalisms-imperialisms and on the other hand by the reality shaped by the capitalist economy in its modern globalised version. We will therefore support neither of them! A further reason for not supporting either one is evident from the fact that within the framework of once – but no longer – fringe theories like those of the 4th political theory, we are faced with the possibility of the creation of a deeply authoritarian informal coalition of disparate countries (from North Korea to Iran and China) on an ascending trajectory of conflict with the whole of a distinct civilization now defined in their eyes as “the West”.

Neutrality, by highlighting the community of those from below, with class characteristics and our dynamic peace-promoting practices is, in our opinion, the appropriate attitude in this case and therefore has nothing to do with an abstract refusal of war. This is all the more true since the consequences of such a war will affect us all. In this light, the revival of the international anti-war movement, which has been extinct for over 15 years (better proof of its total absence during the Syrian civil war) could perhaps have some positive influence on developments. However, judging by the content of public discourse, the low dynamics of collective action today and, above all, the proxy nature of the conflict between NATO and Russia, this possibility should not be considered particularly likely. Nevertheless, the anti-war demand for global nuclear disarmament is proving to be extremely necessary today.

Under the weight of developments in Ukraine there is no doubt that this is a moment of paramount historical importance. We are witnessing a direct violent challenge to the balance of power of the hegemonic centres, which is very interestingly linked to the economic challenge being waged by China. Something that has been discussed for a long time may be happening, but the outcome is really uncertain, especially since the ‘first move’ was made by the Russian military state. At a time when many people, while realising the role of planetary domination in the ongoing social and environmental decline, no longer have the courage to speak out, the conflict in Ukraine paints an extremely contradictory picture that has emerged particularly strong in the pandemic and is of immense value both for the left libertarian forces of our time and for radical forces in general. On the one hand we seem to not know how to survive without some kind of state organization, on the other hand the state leads us to social, health, economic and environmental destruction. How do we pragmatically manage such a complex reality?

The dystopia of a nuclear holocaust or a large-scale ecological (hence social) collapse may still seem distant (?), but we cannot ignore the fact that the forces that gave birth to these prospects as a technical possibility and political-military possibility are precisely the dominant forces today: capital, technocracy and all kinds of military-industrial complexes, nationalism and the modern state.

We conclude with some observations which will shed more light on the rationale that leads us to consider the neutrality stance in this war as the only appropriate option from the point of view of social emancipation. Like any authoritarian leader who wages war, Putin, by attacking Ukraine, is undermining, or at any rate endangering, his own power. However, its end will hopefully come with an internal uprising of the Russian people, especially the most oppressed social groups. Ukraine may of course be the occasion for this, but the battle for its downfall cannot be fought on Ukrainian soil. Among other things, because in this case national war and multilateral conflict signify not only the death of soldiers and civilians who have never supported Russia’s authoritarian regime, but also the nuclear threat. This, of course, implies that the phenomenon of Putin’s authoritarian rule cannot be reduced to the realm of individual psychology and personality, as the liberal position, that presents anti-democrats as ‘madmen’, deliberately and with artificial levity tries to sustain. The problem is not that Putin is “insane”. The problem is that the very juxtaposition of democracy and authoritarianism is now losing the formal validity it once had (which historically has always been more complex, of course).

Democratic political systems and their institutions all over the world, regardless of their specifically national versions, are subjected with undiminished intensity to the web of relations and practices that we call ‘capitalism’. So while states continue to be active forces, the contemporary globalised and interconnected world of transnational relations and antagonisms is regulated by the active presence of capital and the imperatives of accumulation and value valorization that define it. So along with a contradiction – transnational competition tends to undermine the capitalist totality that allows it to exist – there is also a truth that the adherents of liberal discourse cannot bear to hear, as it is a truth that calls for political displacement and personal engagement but also for the questioning of multiple cultural constants and perceptions. The configuration of democratic institutions and their articulation with the legal order and the economy allows for the simultaneous and perpetual reproduction, that is, the permanent co-existence, of representation, authoritarianism and inequality in many social fields and in decision-making. It is also a dynamic relationship that today is increasingly unable to take the formal form of democracy. Modern liberal democracies are technocratic oligarchies separated simply by the presence of a social liberalism (which is also challenged by the neo-right reaction).

The pacified societies of the ‘developed’ world in Europe and America are more likely to abandon Ukraine to the expansionist ambitions of a rising Russia than to fight for it. It is not only the experience of two world wars that is, fortunately, frightening. Material affluence, the ideology of producing and consuming infinite objects, the complete commodification of the world and the trivialization of multiple aspects of life by advertising – all of it, that is, which describe the hegemonic conception of ‘growth’ – guarantee (apart from ecological destruction) that war is removed from the range of culturally available options, not only for the sterile upper classes of ‘Western’ societies, but also for the lower classes and subordinate social groups.

And while we could not rule out the resurgence of European and US nationalisms in the face of a common antagonist, we can hardly imagine European citizens sacrificing themselves on the battlefields fighting against the Russians. Especially when everyone knows that the new ‘cold war’ we have already entered is exclusively a game of the powerful for the control of resources and wealth.

But unfortunately, it is even more difficult, to imagine the oppressed fighting an internationalist, anti-nationalist and anti-colonial battle for the equality of people in all corners of this world. This is despite the fact that from the pandemic and the impending ecological collapse to the devastating war in Ukraine, the great issue at stake is the power of the modern state and of capital, the complete inability to control and be controlled.

The question then becomes more crucial than ever and is this: at the dawn of a new ‘cold war’ and in the era of ecological crisis, will the left libertarian forces of our time be able to present a culturally convincing vision to make people believe again in a different way of organizing collective life that includes as its central point the symbiosis of all beings? Or will they forever distance themselves from people by adhering to simplistic rhetorical schemes that are of little interest to anyone? The questions, though theoretically profound, are primarily practical.

Active neutrality in the war raging in Ukraine is our position, the continuation of the global social war against all those who destroy life and freedom is our promise.

Solidarity with the antifascist anarchists in Ukraine and Russia.

DEATH TO TYRANTS –

LONG LIVE ANARCHY- FIGHT FOR GLOBAL FREEDOM

VOID NETWORK – http://voidnetwork.gr