In his early writings, Marx described the German situation as one in which the only answer to particular problems was the universal solution: global revolution. This is a succinct expression of the difference between a reformist and a revolutionary period: in a reformist period, global revolution remains a dream which, if it does anything, merely lends weight to attempts to change things locally; in a revolutionary period, it becomes clear that nothing will improve without radical global change. In this purely formal sense, 1990 was a revolutionary year: it was plain that partial reforms of the Communist states would not do the job and that a total break was needed to resolve even such everyday problems as making sure there was enough for people to eat.

Where do we stand today with respect to this difference? Are the problems and protests of the last few years signs of an approaching global crisis, or are they just minor obstacles that can be dealt with by means of local interventions? The most remarkable thing about the eruptions is that they are taking place not only, or even primarily, at the weak points in the system, but in places which were until now perceived as success stories. We know why people are protesting in Greece or Spain; but why is there trouble in such prosperous or fast-developing countries as Turkey, Sweden or Brazil? With hindsight, we might see the Khomeini revolution of 1979 as the original ‘trouble in paradise’, given that it happened in a country that was on the fast-track of pro-Western modernisation, and the West’s staunchest ally in the region. Maybe there is something wrong with our notion of paradise.

Before the current wave of protests, Turkey was hot: the very model of a state able to combine a thriving liberal economy with moderate Islamism, fit for Europe, a welcome contrast to the more ‘European’ Greece, caught in an ideological quagmire and bent on economic self-destruction. True, there were ominous signs here and there (Turkey’s denial of the Armenian holocaust; the arrests of journalists; the unresolved status of the Kurds; calls for a greater Turkey which would resuscitate the tradition of the Ottoman Empire; the occasional imposition of religious laws), but these were dismissed as small stains that should not be allowed to taint the overall picture.

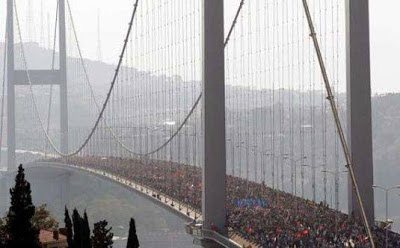

Then the Taksim Square protests exploded. Everyone knows that the planned transformation of a park that borders on Taksim Square in central Istanbul into a shopping centre was not what the protests were ‘really about’, and that a much deeper unease was gaining strength. The same was true of the protests in Brazil in mid-June: what triggered those was a small rise in the cost of public transport, but they went on even after the measure was revoked. Here too the protests had exploded in a country which – according to the media, at least – was enjoying an economic boom and had every reason to feel confident about the future. In this case the protests were apparently supported by the president, Dilma Rousseff, who declared herself delighted by them.

It is crucial that we don’t see the Turkish protests merely as a secular civil society rising up against an authoritarian Islamist regime supported by a silent Muslim majority. What complicates the picture is the protests’ anti-capitalist thrust: protesters intuitively sense that free-market fundamentalism and fundamentalist Islam are not mutually exclusive. The privatisation of public space by an Islamist government shows that the two forms of fundamentalism can work hand in hand: it’s a clear sign that the ‘eternal’ marriage between democracy and capitalism is nearing divorce.

It is also important to recognise that the protesters aren’t pursuing any identifiable ‘real’ goal. The protests are not ‘really’ against global capitalism, ‘really’ against religious fundamentalism, ‘really’ for civil freedoms and democracy, or ‘really’ about any one thing in particular. What the majority of those who have participated in the protests are aware of is a fluid feeling of unease and discontent that sustains and unites various specific demands. The struggle to understand the protests is not just an epistemological one, with journalists and theorists trying to explain their true content; it is also an ontological struggle over the thing itself, which is taking place within the protests themselves. Is this just a struggle against corrupt city administration? Is it a struggle against authoritarian Islamist rule? Is it a struggle against the privatisation of public space? The question is open, and how it is answered will depend on the result of an ongoing political process.

In 2011, when protests were erupting across Europe and the Middle East, many insisted that they shouldn’t be treated as instances of a single global movement. Instead, they argued, each was a response to a specific situation. In Egypt, the protesters wanted what in other countries the Occupy movement was protesting against: ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’. Even among Muslim countries, there were crucial differences: the Arab Spring in Egypt was a protest against a corrupt authoritarian pro-Western regime; the Green Revolution in Iran that began in 2009 was against authoritarian Islamism. It is easy to see how such a particularisation of protest appeals to defenders of the status quo: there is no threat against the global order as such, just a series of separate local problems.

Global capitalism is a complex process which affects different countries in different ways. What unites the protests, for all their multifariousness, is that they are all reactions against different facets of capitalist globalisation. The general tendency of today’s global capitalism is towards further expansion of the market, creeping enclosure of public space, reduction of public services (healthcare, education, culture), and increasingly authoritarian political power. It is in this context that Greeks are protesting against the rule of international financial capital and their own corrupt and inefficient state, which is less and less able to provide basic social services. It is in this context too that Turks are protesting against the commercialisation of public space and against religious authoritarianism; that Egyptians are protesting against a regime supported by the Western powers; that Iranians are protesting against corruption and religious fundamentalism, and so on. None of these protests can be reduced to a single issue. They all deal with a specific combination of at least two issues, one economic (from corruption to inefficiency to capitalism itself), the other politico-ideological (from the demand for democracy to the demand that conventional multi-party democracy be overthrown). The same holds for the Occupy movement. Beneath the profusion of (often confused) statements, the movement had two basic features: first, discontent with capitalism as a system, not just with its particular local corruptions; second, an awareness that the institutionalised form of representative multi-party democracy is not equipped to fight capitalist excess, i.e. democracy has to be reinvented.

Just because the underlying cause of the protests is global capitalism, that doesn’t mean the only solution is directly to overthrow it. Nor is it viable to pursue the pragmatic alternative, which is to deal with individual problems and wait for a radical transformation. That ignores the fact that global capitalism is necessarily inconsistent: market freedom goes hand in hand with US support for its own farmers; preaching democracy goes hand in hand with supporting Saudi Arabia. This inconsistency opens up a space for political intervention: wherever the global capitalist system is forced to violate its own rules, there is an opportunity to insist that it follow those rules. To demand consistency at strategically selected points where the system cannot afford to be consistent is to put pressure on the entire system. The art of politics lies in making particular demands which, while thoroughly realistic, strike at the core of hegemonic ideology and imply much more radical change. Such demands, while feasible and legitimate, are de facto impossible. Obama’s proposal for universal healthcare was such a case, which is why reactions to it were so violent.

A political movement begins with an idea, something to strive for, but in time the idea undergoes a profound transformation – not just a tactical accommodation, but an essential redefinition – because the idea itself becomes part of the process: it becomes overdetermined.* Say a revolt starts with a demand for justice perhaps in the form of a call for a particular law to be repealed. Once people get deeply engaged in it, they become aware that much more than meeting their initial demand would be needed to bring about true justice. The problem is to define what, precisely, the ‘much more’ consists in. The liberal-pragmatic view is that problems can be solved gradually, one by one: ‘People are dying now in Rwanda, so forget about anti-imperialist struggle, let us just prevent the slaughter’; or: ‘We have to fight poverty and racism here and now, not wait for the collapse of the global capitalist order’. John Caputo argued along these lines in After the Death of God (2007):

I would be perfectly happy if the far-left politicians in the United States were able to reform the system by providing universal healthcare, effectively redistributing wealth more equitably with a revised IRS code, effectively restricting campaign financing, enfranchising all voters, treating migrant workers humanely, and effecting a multilateral foreign policy that would integrate American power within the international community, etc, i.e., intervene upon capitalism by means of serious and far-reaching reforms … If after doing all that Badiou and Žižek complained that some Monster called Capitalism still stalks us, I would be inclined to greet that Monster with a yawn.

The problem here is not Caputo’s conclusion: if one could achieve all that within capitalism, why not stay there? The problem is the underlying premise that it’s possible to achieve all that within global capitalism in its present form. What if the malfunctionings of capitalism listed by Caputo aren’t merely contingent perturbations but structural necessities? What if Caputo’s dream is a dream of a universal capitalist order without its symptoms, without the critical points at which its ‘repressed truth’ shows itself?

Today’s protests and revolts are sustained by the combination of overlapping demands, and this accounts for their strength: they fight for (‘normal’, parliamentary) democracy against authoritarian regimes; against racism and sexism, especially when directed at immigrants and refugees; against corruption in politics and business (industrial pollution of the environment etc); for the welfare state against neoliberalism; and for new forms of democracy that reach beyond multi-party rituals. They also question the global capitalist system as such and try to keep alive the idea of a society beyond capitalism. Two traps are to be avoided here: false radicalism (‘what really matters is the abolition of liberal-parliamentary capitalism, all other fights are secondary’), but also false gradualism (‘right now we should fight against military dictatorship and for basic democracy, all dreams of socialism should be put aside for now’). Here there is no shame in recalling the Maoist distinction between principal and secondary antagonisms, between those that matter most in the end and those that dominate now. There are situations in which to insist on the principal antagonism means to miss the opportunity to strike a significant blow in the struggle.

Only a politics that fully takes into account the complexity of overdetermination deserves to be called a strategy. When we join a specific struggle, the key question is: how will our engagement in it or disengagement from it affect other struggles? The general rule is that when a revolt against an oppressive half-democratic regime begins, as with the Middle East in 2011, it is easy to mobilise large crowds with slogans – for democracy, against corruption etc. But we are soon faced with more difficult choices. When the revolt succeeds in its initial goal, we come to realise that what is really bothering us (our lack of freedom, our humiliation, corruption, poor prospects) persists in a new guise, so that we are forced to recognise that there was a flaw in the goal itself. This may mean coming to see that democracy can itself be a form of un-freedom, or that we must demand more than merely political democracy: social and economic life must be democratised too. In short, what we first took as a failure fully to apply a noble principle (democratic freedom) is in fact a failure inherent in the principle itself. This realisation – that failure may be inherent in the principle we’re fighting for – is a big step in a political education.

Representatives of the ruling ideology roll out their entire arsenal to prevent us from reaching this radical conclusion. They tell us that democratic freedom brings its own responsibilities, that it comes at a price, that it is immature to expect too much from democracy. In a free society, they say, we must behave as capitalists investing in our own lives: if we fail to make the necessary sacrifices, or if we come up short in any way, we have no one to blame but ourselves. In a more directly political sense, the US has consistently pursued a strategy of damage control in its foreign policy by re-channelling popular uprisings into acceptable parliamentary-capitalist forms: in South Africa after apartheid, in the Philippines after the fall of Marcos, in Indonesia after Suharto etc. This is where politics proper begins: the question is how to push further once the first, exciting wave of change is over, how to take the next step without succumbing to the ‘totalitarian’ temptation, how to move beyond Mandela without becoming Mugabe.

What would this mean in a concrete case? Let’s compare two neighbouring countries, Greece and Turkey. At first glance, they may seem to be entirely different: Greece is trapped in the ruinous politics of austerity, while Turkey is enjoying an economic boom and is emerging as a new regional superpower. But what if each Turkey generates and contains its own Greece, its own islands of misery? As Brecht put it in his ‘Hollywood Elegies’,

The village of Hollywood was planned according to the notion

People in these parts have of heaven. In these parts

They have come to the conclusion that God

Requiring a heaven and a hell, didn’t need to

Plan two establishments but

Just the one: heaven. It

Serves the unprosperous, unsuccessful

As hell.

This describes today’s ‘global village’ rather well: just apply it to Qatar or Dubai, playgrounds of the rich that are dependent on conditions of near-slavery for immigrant workers. A closer look reveals underlying similarities between Turkey and Greece: privatisation, the enclosure of public space, the dismantling of social services, the rise of authoritarian politics. At an elementary level, Greek and Turkish protesters are engaged in the same struggle. The true path would be to co-ordinate the two struggles, to reject ‘patriotic’ temptations, to leave behind the two countries’ historical enmity and to seek grounds for solidarity. The future of the protests may depend on it.

source: http://www.lrb.co.uk/2013/06/28/slavoj-zizek/trouble-in-paradise