A History of Collective Joy.

By Barbara Ehrenreich.

320 pp. Metropolitan Books/

Henry Holt & Company. $26.

“Take me out with the crowd,” goes the old baseball song. “I love this crowd,” repeats the classic stand-up comic. Every lecturer knows: the larger the group, the more they become an event for themselves, heightening the attention, the laughs or the emotions. At our national political conventions, people wear silly hats and bob up and down to music so stupid it is a parody of music, in order to “demonstrate” a political feeling. Participating in a demonstrative crowd gives joy, as being a mere spectator cannot. Even in a culture where recorded performance has become central, people crave the live event, largely for that group joy.

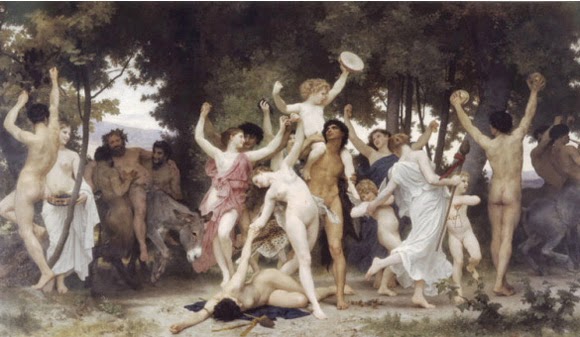

Barbara Ehrenreich wants to affirm the value of ecstatic group celebration. She aligns it with the old precolonial, precapitalist, pre-Christian religions, and with Carnival. The dancing meant by her title has ancient roots; it precedes streets. It also goes beyond them in the modern stadium, where sports and music, watching and performing, all merge. The kind of celebration Ehrenreich celebrates is communal though ungoverned, and anti-hierarchical though ancient. In the god Dionysus she sees a liberating force needed but resisted by modern Western society. She finds Bacchic group joy in carnivals and maypoles, in the dancing rituals of Africa and the Americas, in the French Revolution and in the face-painting of sports fans.

This is an important subject: how much will the human traditions of ecstatic dance, group celebration and Carnival preserve autonomy and help preserve the dignity of individuals? How much will those traditions and our universal, intuitive response to them, be manipulated and co-opted in the interests of uniformity or corporate profit or authoritarian control? Is culture already crippled by a dearth of free communal joy? How much is the celebrating crowd a release valve for energy, how much a potential focus of energy? And what sort of energy?

Ehrenreich identifies these issues, and is ardently on the right side of them. A research journalist, not a thinker or artist, she doesn’t much illuminate them. Her strength, as demonstrated by previous books about low-paying work (“Nickel and Dimed”) and war’s emotional appeal (“Blood Rites”), is her reporter’s nose for subject and information. She assembles juicy quotations, like Martin Luther on dancing: “I can’t bring myself to condemn it, unless it gets out of hand and so causes immoralities or excess. … So long as it’s done decently, I respect the rites and customs of weddings … and I dance, anyway!”

The double-chinned Luther of Cranach’s portrait, cutting a seemingly incongruous peasant jig, harks back to prehistoric forces. Similar forces helped drive the eclectic Hau-hau cult of the Maori in 1864. The Hau-hau resisted colonial injustices under British rule. Deconverting from Christianity, they also incorporated bits of it into their rapturous pole-dance. Ehrenreich quotes a description of their songs as “an extraordinary jumble of Hebrew, English, German, Greek and Italian.”

On the other side — as Ehrenreich sees it, continuing the voice of Dionysus’ antagonist Pentheus, the young king who resists the god in Euripides’ “Bacchae” — here is a Nazi directive for Third Reich dance bands, dug up by Michael Golston (presumably not a pseudonym for Mel Brooks): “On no account will Negroid excesses in tempo (so-called hot jazz) or in solo performances (so-called breaks) be tolerated; so-called jazz compositions may contain at most 10 percent syncopation; the remainder must consist of a natural legato movement devoid of the hysterical rhythmic reverses characteristic of the music of the barbarian races and conducive to dark instincts alien to the German people (so-called riffs).”

This comical passage helps support Ehrenreich’s distinction between the costuming, shouting, dancing, ritual behavior, atavism and collective exultation that she approves of and similar elements in Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies. The fascist event, she says, is a “scripted” spectacle and those attending “did not assemble spontaneously but were rounded up.” A spectacle audience is passive, unlike the rapturously participating crowd at the maypole or the slave revolt (or at Ehrenreich’s preferred parts of the French Revolution). Carnival mocks authority, and is spontaneous. Thus, fans who wear costumes or dance and sing at contemporary sporting events are “carnivalizing” the event.

Such pro-carnival distinctions, with their good-hearted sympathy for the demotic, the colonized, the neglected, the repressed, are extremely vulnerable to counterargument. Even a reader eager (as I am) to prefer carnival over hierarchy will wince at Ehrenreich’s blurry, prefatory disclaimer: “Not every form of ‘irrational’ group behavior will be considered here; panics, crazes, fads and spontaneous ‘mob’ activities do not fall within our purview. Lynchings — or, for that matter, riots — may generate intense excitement and pleasure in their participants, but the focus here is on the kind of events witnessed by Europeans in ‘primitive’ societies and recalled in the European carnival tradition.”

Quotation marks suggest the writer’s need for a straw man who misuses words like “irrational” or “primitive.” The passage continues to defend the ecstatic group events: “These were not spontaneous outbreaks of ‘hysteria,’ as some Europeans tended to imagine; nor were they occasions for the suspension of all inhibitions and a general ‘letting go.’ The behavior that seemed so ‘savage’ and wild to Western observers was in fact deliberately planned, organized, and at all times subject to cultural rules and expectations.”

For fascist events, people “did not assemble spontaneously”; but in another context it is the authentic carnival events that “were not spontaneous outbreaks.” Ehrenreich’s absolute separation between kinds of crowd behavior — the brutal utterly unlike the benign, the fascistic utterly unlike the anticolonial — wobbles.

Nevertheless, she effectively evokes the evils of colonialism from this cultural viewpoint. There is a world of shame and sadness in the African expression she cites for conversion to Christianity: to have “given up dancing.” And ordinary good sense acknowledges her general point: the Nuremberg-style rally is not a peasant wedding, and the maypole is not the lynching tree. But good sense also recognizes that the two kinds of crowd cannot be utterly different in psychology.

This is not a scholarly treatise, but a book to read for quotes, examples and anecdotes. Ehrenreich’s project may be limited, but it is not wrecked, by a warmed-over quality in borrowings from Max Weber, or a breezy equivalence of Wahhabism and Calvinism. Conceptual and logical matters are not the main problem. Style is. How should one write about wild, mass ebullience?

Here is a sentence from Ehrenreich’s chapter “The Rock Rebellion”: “A good part of the frisson of early rock lay in the rhythmic and often sexually suggestive movements of the performers — grinding their hips, thrusting their pelvises, rolling their shoulders, leaping and falling on the floor — ‘rocking,’ in short, as a way of announcing that the ‘new’ music was inseparable from creative, free-form, heat-driven motion.”

And this: “Rock’s contribution was to weigh in decisively on the side of hedonism and against the old puritanical theme of ‘deferred gratification.’ ”

Or this, from her chapter on sports: “In a stadium or at an arena, the audience has been expected for decades to leap up from their seats, shout, wave, and jump up and down with the vicissitudes of the game.”

This language — having rock “weigh in,” phrases like “ ‘rocking,’ in short” and “vicissitudes of the game” — fails to evoke its subject, except maybe by contrast.

Sometimes an interesting idea collapses into a puddle of dead metaphors and weary cadences: “The rise of social hierarchy, anthropologists agree, goes hand in hand with the rise of militarism and war, which are in their own way also usually hostile to the danced rituals of the archaic past.”

This pop anthropology lacks fizz. There’s a yearning, wistful gap between Ehrenreich’s celebration of inebriated dance and her term-paper prose. In that yearning, she disregards the double, ambiguous nature of Dionysus, the deity she calls “the first rock star.” Possibly, her writing indicates a flinching, less than complete apprehension of that shape-shifting Lord of Misrule.

Dionysus seems to embody a force rightfully needed and rightfully feared. Is the abandon of his worshipers humanizing or dehumanizing — or human? Bacchic energy can overthrow tyranny, and it can tyrannize. In her pages on rock, Ehrenreich just barely mentions the Dionysian landmark of Woodstock — and says nothing about the calamity a few months later of Woodstock’s evil twin, Altamont, where an 18-year-old black man was killed. He was kicked and beaten, as well as stabbed multiple times by a member or members of the organization contracted to keep order and guard the stage: the Hell’s Angels, a name that suits the double nature of Dionysus. Which is to say, the double nature of us humans.

In the “Bacchae” of Euripides, Dionysus leads the queen Agave to join the Bacchae — and in a frenzy of delusion, she tears her son Pentheus into bloody pieces, then carries his head as a trophy. After Agave has come to her senses, and realizes what she has done, Dionysus speaks. “I am Dionysus. I am Bacchus,” he says (in the C. K. Williams translation). He proclaims that the horrors he has brought Thebes could have been prevented “if you had understood your mortal natures.” “Dancing in the Streets” takes an honorable, faltering step in that direction.

Robert Pinsky is the author, most recently, of “The Life of David.”

source: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/14/books/review/Pinsky.t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0